Intertestamental Period Paper

advertisement

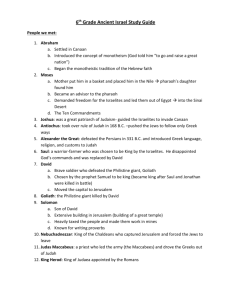

Running Head: INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER Intertestamental Period Paper: Antiochus Epiphanes William Callister Liberty University December 8, 2013 This paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for NBST 510 – New Testament Introduction. INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 2 Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 4 The Persian Empire .......................................................................................................... 4 Cyrus the Great (539-530 BC) ........................................................................................ 4 The Decline of Israel (530-331 BC) ............................................................................... 5 The Greek Conquerors ..................................................................................................... 6 Alexander the Great (331-320 BC) ................................................................................. 6 The Ptolemaic Period (320-198 BC)............................................................................... 6 The Seleucid Period (198-167 BC) ................................................................................. 7 Antiochus IV Epiphanes as a Ruler ............................................................................ 8 Antiochus Epiphanes and Egypt ................................................................................. 9 Persecution of Jews under Antiochus Epiphanes ....................................................... 9 Jewish Self-Rule .............................................................................................................. 11 The Maccabees (167-135 BC) ...................................................................................... 11 The Hasmoneans (135-63 BC)...................................................................................... 12 The Roman Empire......................................................................................................... 13 Herodian Dynasty (40 BC-AD 6) ................................................................................. 13 Imperial Rule in Judea (AD 6-70) ................................................................................ 14 The Destruction of the Second Temple (AD 70) .......................................................... 14 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... 14 Bibliography .................................................................................................................... 16 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 3 Abstract The second temple period is the period of approximately 585 years between the rebuilding of the temple (second temple) in Jerusalem in 515 BC and its destruction in AD 70. During this time, the people of Israel (Jews) suffered as a conquered nation, under the Persians and then the Greeks. They regained independence for a short period of about one hundred years, before once again succumbing to the oppressive rule of foreign invaders—Rome. During the period of subservience to the Greeks, the Jews faced their greatest oppression under the rule of Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus sought to not only suppress the Jewish religion, but to completely eradicate it. This was the catalyst that set the stage for the Israelites to regain some form of independence, which in turn prepared the way for the stability of the Roman Empire, the coming of the Messiah—Jesus Christ, and the spread of the Gospel. INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 4 Introduction In their extensive introduction to the New Testament, Andreas J. Kostenberger, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles place the second temple period as beginning in 515 BC, when the second temple was completed.1 It could also be argued that the second temple period begun approximately twenty years prior to this (c. 539), when Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and allowed the Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem. This period ended around AD 70, when the Romans attacked Jerusalem and razed the temple to the ground. The Persian Empire In approximately 539, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon. Cyrus accomplished an incredible feat of engineering, in his bid to conquer Babylon. It is reported that he had a large trench dug to divert the Euphrates River, which flowed under the walls of Babylon. In doing so, his army was able to march under the walls of Babylon, in water that only reached “about midway up a man’s thigh.”2 The Old Testament book of Ezra reports that in Cyrus’ first year as king, he issued a proclamation calling for the building of a house for “the Lord God of heaven…at Jerusalem” (Ezra 1:2, KJV). Cyrus the Great (539-530 BC)3 Isaiah prophesied of this rebuilding, when God promised to use Cyrus as a shepherd to the people of Israel, who would establish the foundation of the second temple (Isa. 44:28). It is important to note the level of impact God had in Cyrus’ life, preparing the way and leading him in his conquests, despite the reality that Cyrus was in no way a follower of the one, true God (Isa. 1 Andreas J. Kostenberger, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown (Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 2009), 59. 2 Daniel T. Potts, Mesopotamian Civilization: The Materials Foundation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), 23. 3 Archaeological Study Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 669. INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 5 45:1-4). God used this pagan ruler to bring about the return of the exiles and the rebuilding of His temple in Jerusalem. In spite of the large assistance that Cyrus gave to the returning exiles, it still took over twenty years for them to complete the temple, which was finally finished and dedicated around 515.4 The Old Testament books of Haggai and Zechariah offer insight into some of the issues that the Jews were facing, offering them encouragement to continue the rebuilding of the temple.5 The Decline of Israel (530-331 BC) Haggai and Zechariah offer some of the last canonical records of the second temple period, with their accounts of the rebuilding of the temple; while Nehemiah deals with the exiles who return to accomplish the restoration of the city walls. The only other record is found in Malachi, which likely occurred many decades after the completion of the temple but still under the rule of Persia.6 The primary extra-biblical records for this time period are found in the works of Josephus and the apocryphal books of first and second Maccabees. These offer some excellent insight into the period, though without the inerrancy found in the biblical records. It becomes clear, in the writings of Malachi and Nehemiah, that the people of Israel have quickly fallen away from God’s plan for Israel. While they had not returned to the pagan cults, as their forefathers had, they had resorted to a level of “dead orthodoxy,”7 that left them dead and apathetic instead of enjoying the vibrant, joyful life that God had intended for them. They had lost hope for any kind of future as a people. They had lost their faith in God, and replaced it with religiosity. They no longer had the hope that faith provides, and were left with nothing but a 4 Kostenberger, et al., 60. Archaeological Study Bible, 1521 & 1526. 6 Ibid., 1545. 7 Ibid. 5 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 6 ritualistic religion. They lived a life of fear, in which their only hope and joy came in performing enough rituals and good works to be able to earn their way into paradise. The Greek Conquerors The second temple was completed for less than two hundred years when the Greeks took the controlling interest in the Middle East, including the Jews in Israel.8 This occurred in 331, when Alexander the Great defeated Darius at the battle of Gaugamela.9 The Greeks ruled the Middle East, and most of the known world, for about one hundred and sixty years. Alexander’s death in 320 left a void in the government, which resulted in a division of the empire into four distinct groups. Alexander the Great (331-320 BC) Alexander faced little opposition from the subservient nations of the Persian Empire. Flavius Josephus reports that the high priest at Jerusalem, upon hearing that Alexander was nearing Jerusalem, opened the gates of Jerusalem and went out to welcome Alexander as the rightful king of the region.10 The Egyptians welcomed Alexander as their new ruler,11 and Darius was forced into captivity by his own noblemen, following his defeat at Gaugamela.12 Alexander ruled the newly expanded Greek Empire until his death in 320. The Ptolemaic Period (320-198 BC) Following the death of Alexander, the Greeks attempted to maintain the empire through a variety of power plays.13 This finally came to an end in 301, when the empire was divided 8 Kostenberger, et al., 65. Ibid., 66. 10 Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, BibleStudyTools.com, http://www.biblestudytools.com/history/flavius-josephus/antiquities-jews/book-11/chapter-8.html (accessed December 7, 2013), 11.8.4. 11 Kostenberger, et al., 66. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 9 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 7 amongst Alexander’s four leading generals.14 Greece was taken by Cassander, only to later fall to the growing Roman Empire. Syria was controlled by the Seleucids, who would later wrest control of Asia Minor from Lysimachus. Ptolemy I was the only general who managed to develop a successful kingdom, which consisted primarily of Egypt but stretched as far as Judea.15 The Ptolemaic rule of Judea has left very little evidence for analysis. It would seem that the region existed as something of a temple state run by the Jewish high priest.16 The Ptolemaic rulers seemed to be primarily focused on collecting large amounts of revenue through taxation and ensuring secure travel through the trans-Jordan region for trade. It was during this period of rule under the Ptolemies that many Jews in Egypt were sent to Alexandria, and then throughout the rest of the Mediterranean.17 Jews in the Potlemaic kingdom, particularly those who embraced the Greek lifestyle, experienced many blessings. While they were still a subservient people under a foreign ruler, they enjoyed great successes under the hands-off approach of the Ptolemies. This would be especially true for those who had been scattered throughout the Mediterranean world. However, under the reign of the Seleucid rulers, the Jewish people still in the land of Judea would soon face greater trials than they could have imagined. The Seleucid Period (198-167 BC) The Seleucids, or Syrians, only managed to maintain control of the Palestinian region for approximately three decades. In this time, Jews would face extreme persecution, to the point that they were driven to rebel against their foreign rulers and claim their freedom for themselves. 14 Kostenberger, et al., 67. Ibid. 16 Ibid., 68. 17 Ibid. 15 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 8 Some have compared this rebellion as being very similar to the rebellion carried out by the patriots of the American Revolution.18 Antiochus III made a formidable enemy in the growing nation of Rome, which resulted in the imprisonment of his son (Antiochus IV) and the levying of exorbitant tributes to Rome on a monthly basis.19 Antiochus IV spent twelve years as a hostage in Rome, as a result of his father’s actions against the Roman forces at Magnesia.20 This, along with the heavy tributes sent to Rome, would play a critical role in the development of the kingdom under the rule of Antiochus IV. Antiochus IV Epiphanes as a Ruler Life under the rule of Antiochus IV was far from easy. Following his release from Rome, he inherited a tragically damaged kingdom. The loss his father (Antiochus III) had suffered at Magnesia resulted in massive financial losses, as well as severely diminished political and military stature in the region.21 Antiochus IV took the throne in approximately 175 BC. There seems to be some consensus that Antiochus IV was more interested in expanding his kingdom, rather than focusing on governing what he already possessed.22 Antiochus IV was thoroughly committed to spreading the Greek culture throughout the world; though it is clear that his time in Rome as a hostage gave him an appreciation of the Roman perspective and worldview.23 When faced with some of the schemes of other Greeks, against the Romans, Antiochus chose to remain apart from any efforts that might position his 18 The Glenn Beck Program, The Blaze TV, December 5, 2013. Kostenberger, et al., 68. 20 M. Gwyn Morgan, “The Perils of Schematism: Polybius, Antiochus Epiphanes, and the ‘Day of Eleusis,’” Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschechte 39.1 (1990), 50. 21 Joseph Ward Swain, “Antiochus Epiphanes and Egypt,” Classical Philology 39.2 (1994), 75. 22 Ibid., 74. 23 Morgan, 54. 19 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 9 damaged kingdom as a target of the Roman war machine.24 He worked to avoid antagonizing the Roman kingdom, even to his own embarrassment and shame.25 Antiochus Epiphanes and Egypt Antiochus gave Egypt little thought, as an enemy, as it experienced a strong connection with Rome, which Antiochus did not wish to challenge. However, this changed when word came to him that they were preparing to attack and regain Coelesyria—a wealthy country that Antiochus III had captured from Egypt in 201.26 Antiochus IV went to war with Egypt in 169, using the excuse of endorsing Philometer as the rightful king, and fighting against the Egyptian regents—Eulaeus and Lenaeus—that were working to wrest control away from the Greek ruler under the Ptolemaic rule.27 Once again, Antiochus prepared to go to war against Egypt in 168. The Ptolemaic ruler sought the aid of others in the Greek world, but to no avail.28 This frustrated Antiochus’ desire for a unified Greek kingdom that would cover the whole world. His attempts to wage war against Egypt were finally thwarted, not by an uprising within the Greek world, but through Roman interaction on behalf of the Ptolemies. Antiochus faced an embarrassing withdrawal before the Roman Legate Popilius Laenas, as mentioned above. Persecution of Jews under Antiochus Epiphanes It is likely that the Jews offered Antiochus the least amount of trouble, in comparison to the other people groups he ruled over; however, much more is known about the interaction of Antiochus and the Jews.29 Many Christians are familiar with the stories of Antiochus Epiphanes, 24 Morgan, 54. Kostenberger, et al., 69. 26 Swain, 75. 27 Ibid., 81-83. 28 Ibid., 86. 29 Ibid., 76. 25 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 10 and the rabid attacks he made on the followers of the Jewish faith. The apocryphal book of 2 Maccabees would seem to indicate that the oppression most Jews faced was not directly from Antiochus. The bulk of their oppression, initially, came from those who gained the position of high priest, through various, criminal means (2 Maccabees 4). This being said, the bulk of Antiochus’ attacks on the Jews came as a result of a misunderstanding. While Antiochus was in Egypt for the second war (168), it was reported that he was dead. Jason took this opportunity to stage a coup against the high priest, Menelaus.30 Upon his return, Antiochus ordered a tragic massacre of thousands of men, women, and children; he believed that the ousting of Menelaus had been supported by the Jewish people. This was also the time when Antiochus began a thorough confiscation of all valuables in the temple treasury, and when he began his most severe attack on the Jewish religion. It is possible that Antiochus was caught in the midst of several tragic crosswinds, which left him off balance. He had just suffered an embarrassing withdrawal before a Roman Legate, he returned to Jerusalem to find one of his officials ousted by a usurper, and the Jewish beliefs and customs stood in stark contrast to the Greek worldview that he sought to spread throughout the world. It is likely that all of these conflicts in his life converged at one point, and urged him down the course of action he proceeded along. 2 Maccabees 6:1-11 offers insight into the level of barbarism that Antiochus was willing to go, in order to drive the Jewish people away from their adherence to the Law and into the arms of the Greek religions. The temple was defiled, dedicated to the Greek god Zeus, and all manner of ungodly acts were performed within its hallowed walls. Susan Haber identifies three specific Jewish practices that could result in the death penalty under Antiochus’ reign, according to 2 30 Kostenberger, et al., 69. INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 11 Maccabees. Specifically, she mentions the circumcision of babies, observance of the Sabbath, and adherence to the Jewish dietary laws.31 These persecutions would be the catalyst that drove the Jews to rebel against Antiochus and throw off the yoke of Greek rule. Jewish Self-Rule In 167, Antiochus Epiphanes was still on the throne and persecuting the Jewish people for their refusal to put aside their ancestral faith to adopt the Greek lifestyle and worldview. However, it was at this time that the Jews began to feel the pressure to fight back. One man, and his friends, took a stand against the tyranny of an oppressive ruler who sought to eliminate their ancestral heritage. The Maccabees (167-135 BC) 2 Maccabees 8:1-7 tells of the efforts of Judas Maccabeus. He, and his followers, secretly gathered an army of approximately 6,000 Jewish men who had stayed true to their Jewish faith. His army progressed, attacking and destroying Gentile towns and villages, moving closer to Jerusalem. Over the course of approximately four years, the Jews waged a successful campaign against the Greek oppressors, recapturing Jerusalem and turning back every army that Antiochus and his generals could muster against them. Finally, in a fit of rage, Antiochus promised to “turn Jerusalem into a graveyard full of Jews” (2 Macc. 9:4, GNT). It was at this time that 2 Maccabees reports that he was struck with intense abdominal pains (9:5), followed by an intense after falling from his chariot (9:7), and ultimately he was consumed with internal worms that ate away at his body (9:9). While the time of the Maccabees was not truly a period of self-rule—they still were technically under the Susan Haber, “Living and Dying for the Law: The Mother-martyrs of 2 Maccabees,” Women in Judaism: A Multidisciplinary Journal 4.1 (2006), para 3. 31 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 12 authority of the Syrian rulers—they did experience a much greater amount of freedom, as their military victories made them formidable enemies to the rulers. Appeasement seems to have been the general method of dealing with the Maccabean leaders, by the Syrian rulers of the time. It was not until the end of Simon Maccabeus’ time as high priest and ruler of Jewish political and military ventures that the Jews truly experienced a period of autonomy. The Hasmoneans (135-63 BC) In approximately 135, John Hyrcanus became the first of the Hasmonean rulers. Though generally regarded as a conservative, theologically, he is reported to have switched from the Pharisees to the Sadducees—two Jewish religious orders that developed during the Hasmonean period.32 The Hasmoneans ruled effectively for almost seventy years, with varied results. John Hyrcanus began well, with conservative religious views, focusing on securing his nation, rather than expanding it. Under future rulers, the Hasmonean leaders recaptured lost portions of the Promised Land and expanded their borders.33 In keeping with their heritage, this progress and stability within the nation led to deeper levels of corruption and carnality in the rulers. Eventually, in 63, Roman armies led by General Pompey took advantage of instability caused by conflict between two contenders for the throne—Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. He conquered Jerusalem and made Judea a subject of the governor of Syria, who was in turn a subject of the Roman Empire.34 In 63 BC, the period of Jewish self-rule had come to a close, and the Jews were once again finding themselves the subject of a foreign, pagan power. 32 Kostenberger, et al., 71. Ibid., 72. 34 Ibid., 73. 33 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 13 The Roman Empire The Roman general, Pompey, saw the conflict amongst the rulers of Judea as an opportunity, and he seized it. He entered the fray, while the two would-be rulers were arguing amongst themselves, and captured the city of Jerusalem, bringing it into the Roman Empire as a captured nation under the rule of the governor of Syria. Some conflict remained amongst those who wished to maintain some semblance of power under the new system. Herodian Dynasty (40 BC-AD 6) One of the individuals who had sought to gain some power in Judea was the son of Antipater, Herod. Seeing that his opportunities were limited, and he may have been in some danger, he fled to Rome. In 40, he was given the title “king of Judea” by the Senate in Rome.35 Returning to Jerusalem, he still faced some challenges. In his absence, Antigonus had assumed the role of leadership over Judea. It was approximately three years before he was able to successfully oust Antigonus, with the help of Antony, and claim full leadership over his little kingdom. Herod was a cruel and paranoid ruler, who suffered from dementia during his role as “king.”36 Despite his flaws, he was a skillful, albeit cruel, civil administrator.37 His son, Archelaus, was as cruel and paranoid as his father but lacked the administrative skills that his father’s administration demonstrated.38 As a result, Jerusalem lost more independence as it came under direct control from Rome, as opposed to the secondary role that Rome played through the Syrian governor.39 35 Kostenberger, et al., 74. Ibid., 74-75. 37 Ibid., 75. 38 Ibid. 39 Ibid. 36 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 14 Imperial Rule in Judea (AD 6-70) Augustus banished Herod’s son, Archelaus, in AD 6, putting a temporary end to the Herodian dynasty for roughly the next three decades. This also was the beginning of the period of direct imperial rule of Judea.40 Rome was no longer content to allow Judea the same amount of leniency it had experienced under the Herodians. The Herodian dynasty would once again find a place in Judean politics, when Herod’s grandson and great-grandson (Herod Agrippa I and Herod Agrippa II, respectively) assumed the role of king of Judea and Palestine in 41 and 50, respectively.41 The Destruction of the Second Temple (AD 70) In 66, the last Roman procurator of Judea, Florus, instigated a Jewish revolt when he looted the temple treasury.42 This was the tipping point for the empire. The revolt in 66 continued for several years, until climaxing in 70 with the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem. The Jewish people likely longed for the days of Antiochus’ defiling of the temple, as they watched the Roman legions completely destroy the temple and raze the city. Conclusion The savage attack that Antiochus Epiphanes brought against the Jews in 168 BC can be seen as the result of several contributing factors. The humiliation he faced in Egypt, the perceived betrayal by the Jewish people, and his strong desire to see Greek culture spread through the whole earth all served as contributing factors for his attack on the Jews. In the same way, there were many factors that combined to make the introduction of Jesus Christ and the gospel a success. The spread of Greek as a common language, the stability provided by the 40 Kostenberger, et al., 76. Ibid., 62. 42 Ibid., 78. 41 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER Roman empire, and the dispersion of the Jews (many of them had become followers of Christ) after the destruction of the temple were all critical components in helping the gospel to spread throughout the known, and unknown, world. 15 INTERTESTAMENTAL PERIOD PAPER 16 Bibliography Archaeological Study Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005. Haber, Susan. "Living and Dying for the Law: The Mother-martyrs of 2 Maccabees." Women in Judaism, 2006: 1-14. Josephus, Flavius. "Chapter 4 - The Works of Flavius Josephus." BibleStudyTools.com. n.d. http://www.biblestudytools.com/history/flavius-josephus/antiquities-jews/book11/chapter-4.html (accessed December 8, 2013). Kostenberger, Andreas, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles. The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 2010. Morgan, M. Gwyn. "The Perils of Schematism: Polybius, Antiochus Epiphanes and the 'Day of Eleusis'." Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 1990: 37-76. Potts, Daniel T. Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997. The Glenn Beck Program. Performed by Erick Stakelbeck. December 5, 2013. Swain, Joseph Ward. "Antiochus Epiphanes and Egypt." Classic Philology, 1944: 73-94.