Modern History Handbook 2015 - 2016

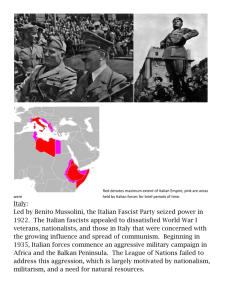

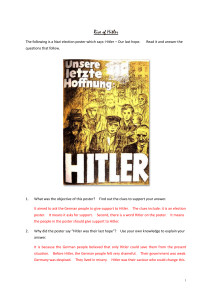

advertisement