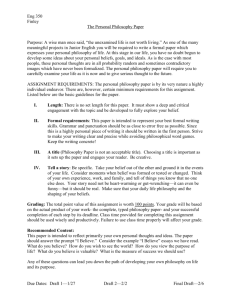

Philosophy as Quest - Oregon State University

advertisement