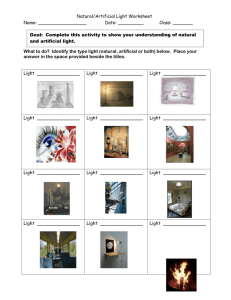

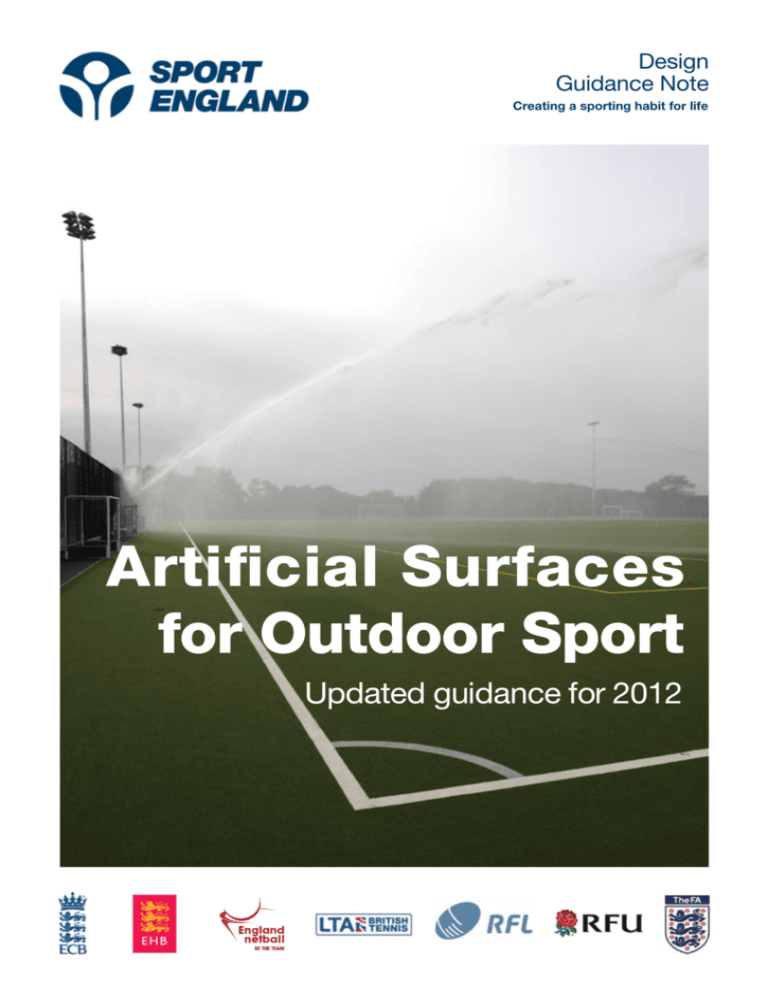

Artificial Surfaces for Outdoor Sport

advertisement