The Haber-Bosch Process

advertisement

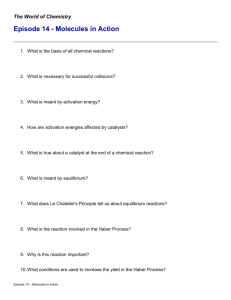

The Haber-Bosch Process By, Max MacMackin & Cory Lillie It’s the end of the nineteenth century, the human population has continued its population growth but the earth as a whole had already been discovered during the various periods of industrialization of the human race. There is no new land to be found and much of the land that is still available for farming has been farmed for hundreds of centuries. “Cereal crops were the staple of the human diet and as a result farmers had to develop a way to successfully grow enough crops to support the population. They eventually learned that fields needed to be able to rest between harvests and that cereal crops and grains could not be the only crop planted. In order to restore their fields, farmers began planting other crops and when they planted legumes they realized that the cereal crops planted later did better. It was later learned that legumes are important to the restoration of agriculture fields because they add nitrogen to the soil.” (site1) The land was still very used up despite this newfound way to help revitalize the soil, some scientists expected mass starvation if a solution could not be found to make crops more productive in overly farmed areas and to increase grain production and agriculture in new areas like Russia, the Americas and Australia. It was only “in the late 1800's and early 1900's scientists, mainly chemists, began looking for ways to develop fertilizers by artificially fixing nitrogen the way legumes do in their roots. ”(site1) It was Fritz Haber, in 1909, who first found a way to synthesize ammonia in a lab and later Carl Bosch, in 1912, who turned Fritz Haber's process into something that could be done on a commercial level. It is believed that this process currently “ is estimated to support food for at least a third of the Earth’s population.”(Helmenstine). Fritz Haber, the second half of the Haber-Bosch process, was a German scientist. He was born on December 9, 1868 in Breslau, Prussia. He was born into one of the oldest families of the town, as the son of Siegfried Haber, a merchant of dyes and pigments although his mother did die during childbirth leading to a lifelong strain on his relationship with his father. Haber received his early education at the local gymnasium although he did many chemical experiments throughout his childhood. He began his study of chemistry in 1886 but was interrupted by a year of military service after a year and a half of college at Heidelberg. After his military service he transferred to the Charlottenberg Technische Hochschule in Berlin, from which he received a doctorate in 1891 for work done under Karl Liebermann. After graduation there was a short period of his life, about 3 years, that found Haber doing various industrial work, some of which was for his father, with short periods of time over those years spent doing some postdoctoral study at the Technische Hochschule in Zürich and the University of Jena. Haber was married twice in his life. His first wife was Clara Immerwahr with whom he has a son Hermann. His second marriage was to Charlotta Nathan with whom he had to kids, a daughter, Eva, and son, Ludwig. Both marriages ended in Haber’s wife leaving him. “In 1894 Haber was appointed as an assistant in the Department of Chemical and Fuel Technology at the Fridericiana Technische Hochschule in Karlsruhe. Here he rapidly worked his way through the academic ranks to become a full professor in 1906.”(site4) It was in 1904 that Haber started to form a growing interest in the thermodynamics of gas reactions where his work in this area soon focused on the synthesis of ammonia gas from nitrogen and hydrogen gas and its potential as a method of nitrogen fixation. “By 1908 Haber was able to show that the use of high pressures in combination with a suitable catalyst made ammonia synthesis practical, and the next year the process was turned over to the German chemist Carl Bosch at BASF Aktiengesellschaft for industrial development of what is now known as the Haber-Bosch process.”(site4) For his work in this field the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1918 was awarded to Fritz Haber "for the synthesis of ammonia from its elements". German chemist Carl Bosch is the other half of the namesake to the Haber-Bosch process. Carl Bosch was born at Cologne, Germany on August 27, 1874, and grew up there with his father, Carl Friedrich whom owned a wholesales firm with a workshop for gas and water installations. Carl was the eldest of six kids and grew up in a very opened-minded atmosphere, uncharacteristic of the time, Carl’s father never punished his kids in any way. “From 1894 to 1896 he studied metallurgy and mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Charlottenburg, but started reading chemistry at Leipzig University in 1896. He graduated under Professor Wislicenus with a paper on organic chemistry in 1898. He entered the employ of the Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik, Ludwigshafen, Rhine as a chemist in April 1899 and participated actively in the development of the then new industry of synthetic indigo under the guidance of Dr. Rudolf Knietsch.” (SITE5) Around 1900 Carl Bosch started to become interested in the problem of the fixing nitrogen from the air to a usable form. Some of his first experiments to do with this issue involved metal cyanides and nitrides. Bosch got a huge opportunity when, in 1908, “the Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik acquired the process of high-pressure synthesis of ammonia, which had been developed by Fritz Haber at the Technische Hochschule in Karlsruhe.”(site5) Bosch’s job was to take Haber’s table top highpressure synthesis of ammonia and developing this process on a large, industrial scale. He accomplished this and from this work Bosch succeeded in working out methods for the industrial production of nitrogen fertilizers, thus providing practically every country in the world with sufficient fertilizers for agricultural purposes. “In 1931 Bosch was awarded the highest international honor, the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, jointly with Friedrich Bergius, for their contributions to the invention and development of chemical high pressure methods.”(SITE5) “In 1898 the British chemist William Crookes warned that the world’s population would soon outstrip its food production unless crop yields were increased through the use of nitrogen fertilizers.”(site4) In 1905, German chemist Fritz Haber published The Thermodynamics of Technical Gas Reactions (Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen). This book more concerned about the industrial application of chemistry than to its theoretical study. In it, Haber inserted the results of his study of the equilibrium equation of ammonia: N2 (g) + 3 H2 (g) 2 NH3 (g) + ΔH. This equation is what gave Haber an upper hand in later endeavors in nitrogen fixation. In 1907, spurred by a scientific rivalry with Walther Nernst, solving the nitrogen fixation problem became Haber's top priority. A few years later, Haber used results published by Nernst on the chemical equilibrium of ammonia and his own familiarity with high-pressure chemistry and the liquefaction of air to develop a new nitrogen fixation process. “The Haber process takes nitrogen gas from air and combines it with molecular hydrogen gas to form ammonia gas. This is an exothermic reaction, meaning it releases energy so that the sum of the enthalpies of N2 and H2 (the reactants) is greater than the enthalpy of NH3 (the products). N2(g) + 3H2(g) → 2NH3(g) ΔH=-92.4 kJ which is a reversible reaction: 2NH3(g) → N2(g) + 3H2(g) ΔH=+ 92.4 kJ mol-1. In layman's terms, methane and steam combine to form hydrogen and carbon monoxide, which in turn releases hydrogen. The hydrogen then combines with oxygen from the air to produce water. Finally, nitrogen gas is released which combines with hydrogen gas to form ammonia. This takes place under high pressure and temperature and with a catalyst”(site7) It became Carl Bosch's job to take this process from the small tabletop process in its current form to an industrial sized plant when Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik acquired the process. “This task involved the construction of plant and apparatus which would stand up to working at high gas pressure and high reaction temperatures. Haber's catalysts, osmium and uranium had to be replaced by a contact substance that would be both cheaper and more easily available. Bosch and his collaborators found the solution by using pure iron with certain additives. Further problems that had to be solved were the construction of safe high-pressurized blast furnaces, a cheap way of producing and cleaning the gases necessary for the synthesis of ammonia. Step by step Bosch went on to using increasingly larger manufacturing units and thus created the industry that deals with the production of synthetic ammonia according to the high-pressure process. From this work resulted the second task of making the thus won ammonia available for use in industry and agriculture. Bosch succeeded in working out methods for the industrial production of nitrogen fertilizers, thus providing practically every country in the world with sufficient fertilizers for agricultural purposes. ”(http://www.nobelprize.org/) Fritz Haber will always be remembered for his work in the creation of the Haber-Bosch process, but when he was alive, he had a totally different reputation. Haber got a long with his colleagues at work but when it came to his personal life, it was a complicated situation. One Haber’s reputations I found was one of an absent husband. In the summer of 1901, Fritz and his fiancée Clara planned to take a hiking trip together. When Fritz went to buy tickets for the train, he had his fiancée wait for him outside and after awhile she went into the station to find that her fiancée had already boarded a train and left her there. He would constantly show up later for dinner, and would scold his wife when she would visit him at school. His wife ended up committing suicide ten days after the first use of chemical warfare. Some believe she did so as a protest. (site) When I think of the reputations of Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch in today’s society, the first thing that comes to my mind is the impact they had on the world’s population. The Haber-Bosch process not only helped increase the world’s population with the introduction of new fertilizers; it also decreased the population with the use of chemical warfare. Fritz Haber was the director of the Institute for Physical Chemistry that made poisonous chlorine gas. He actively participated in its development and was an advocate for its use, even though the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 banned poisonous gas. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Haber was asked to devise a method of producing nitric acid for making high explosives. Later he became one of the principals in the German chemical warfare effort, devising weapons and gas masks, which led to protests against his Nobel Prize in 1918. Fritz Haber was the proud recipient of the Iron Cross as an award for his work. Carl Bosch, working for BASF, a giant German company, converted the ammonia production he helped engineer into munitions production for World War I. Ammonia is the key to fixing nitrogen, the chemical necessary to make either fertilizer or explosives. Bosch took an active part in designing a new plant deep inside Germany that provided Germany with the munitions they needed to stretch out the war. Both Haber and Bosch were richly rewarded, within Germany with honors and money, and outside of Germany – both won the Nobel Prize. But both were directly responsible for the deaths of millions of people in World War I. Bibliography • "Fritz Haber - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2013. Web. 31 Mar 2014. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1918/haber-bio.html> • "Carl Bosch - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2013. Web. 31 Mar 2014. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1931/bosch-bio.html> • Helmenstine, Anne M. "Haber Process or Haber-Bosch Process." About.com Chemistry. About.com Chemistry. 30 Mar. 2014 <http://chemistry.about.com/od/chemicalreactions/fl/Haber-Bosch-Process.htm>. • Goran, Morris Herbert. The Story of Fritz Haber. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1967. Print.