Haber process: - Binus Repository

advertisement

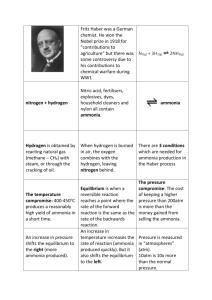

Haber process: This process involves the production of ammonia from the elements, nitrogen and hydrogen: N2(g) + 3H2(g) <----> 2NH3(g) Epilogue: Remarks on Science and the Social Order (taken from Leonard K. Nash (Emeritus Professor of Chemistry at Harvard University) Elements of Chemical Thermodynamics, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1962, pp.89-90) Haber began his studies of the synthesis of ammonia in 1904. On the basis of calculations like that given above (equations which make use of constant of equilibrium expressions), confirmed by a great many experiments, he came to conceive the process for which he took the key patent in 1908. This patent describes a continuous recirculation of the process gas --- using heat exchangers but maintaining throughout the same high pressure --- in such fashion that even at low equilibrium concentration of ammonia is removed continuously, by condensation, while the remaining process gas is reheated and passed again over the catalyst. By 1909 Haber was able to demonstrate, to a representative of the Badische Anilin und Sodafabrik, a tiny pilot system producing about 80 grams of liquid ammonia per hour. The many remaining problems of the synthesis were solved in the laboratories of this concern which --- five years later, in 1914 --- had managed to bring the Haber process into quantity production. That date is significant. All the high explosives used in the World War of 1914-1918?absolutely require nitric acid which, at the outbreak of the World War I, was derived almost exclusively from Chile saltpeter, NaNO3. A country cut off from its supply of this mineral, as Germany was by the British blockade, could, however, still obtain nitric acid if only it could fix atmospheric nitrogen as ammonia, since ammonia can be converted into nitric acid by a series of steps summarized in the equation NH3 + 2O2 --> HNO3 + H2O The Haber process was brought into production not a minute too early for Germany. Because of the Haber process, Germany avoided early defeat, the war was prolonged. Is it a blessing so to be saved? Prolongation of the war so depleted Germany, and so embittered her foes, that the postwar situation may be thought to have made inevitable the rise of a Hitler. If this be so, the Haber process was no blessing for Germany, and certainly no blessing for Haber, who, with the rise of Hitler, became "the Jew Haber" driven to his death in exile. In the late 19th century there were prophets of disaster who foretold the early doom of urban civilization, an early resurgence of chronic famine, consequent to the ultimately inevitable exhaustion of the supply of Chile saltpeter, the major source of fixed nitrogen for agricultural fertilizer. The Haber process frees us once and for all from this threat? ?The scientist makes an ethical judgment, and assumes a moral responsibility, when he elects to participate in the technological exploitation of science for destructive purposes. "Social demand" may applaud, but cannot justify, such a decision --- any more than it can the decision of the smith who turns iron into swords rather than ploughshares. But science, scientific knowledge, is ethically as neutral as the iron: "evil"; only when men forge it as a sword; "good" when beaten into a ploughshare. Conceivably there is some knowledge that can lead only to "evil"; certainly there is none that can lead only to "good"? One can never deny the possibility of what Sophocles though a certainty, "No great thing ever enters human life without a curse." Unlike the Greeks, however, we have an abiding faith in the possibility of ameliorating the human condition which emboldens us to push on in science, and elsewhere, with Whitehead's conviction that: "Panic of error is the death of progress."

![mic_class10_10.ppt [Compatibility Mode]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008220705_1-eb9498ce6cd0ab3209762ef99981a3a3-300x300.png)