Could do better - Cambridge Assessment

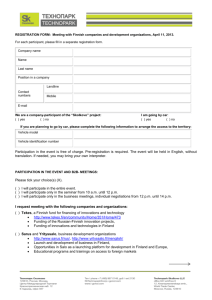

advertisement