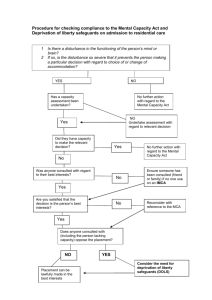

Mental Capacity Act 2005

advertisement