Conflict and Innovation 1 Innovation and Cognitive Conflict

advertisement

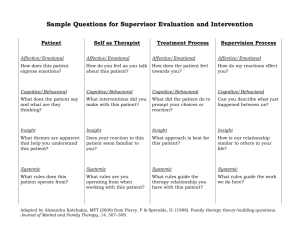

Conflict and Innovation 1 Innovation and Cognitive Conflict: Interventions Designed to Mitigate the Harms of Affective Conflict Tim Cole, DePaul University Dan Letchinger, DePaul University The expansion of entrepreneurial education across campus (Morris, Kuratko & Cornwall, 2013) not only provides students with new opportunities, skills and insights; it also incorporates voices from different disciplines into the conversation about how entrepreneurship can be taught and practiced. Such a multi-disciplinary approach is certain to foster innovation within the field of entrepreneurship. Conflict and Innovation As scholars with a background in interpersonal communication, we would like to offer our perspective on an essential element of the process of innovation – the role of conflict. Specifically, we would like to address how conflict can best be managed when seeking innovative ideas and outcomes. We were somewhat surprised to discover that entrepreneurial educators often advocate adopting a collaborative approach to conflict (see, Kuratko, Hornsby & Goldsby, p. 219). As interpersonal scholars, we see things differently. The point of adopting a collaborative conflict style is not to arrive at the best possible solution. Collaborative conflict is designed to keep close, interpersonal relationships in tact – to maintain cohesiveness – an idea best captured by the saying: “Would you rather be right or happy?” Cognitive Conflict. However, when the outcomes at stake involve getting it “right” – or pivoting in a new direction – conflict can be helpful. A confrontational approach to disputes, called “cognitive” conflict is a necessary component of the process of innovation (Mooney, Conflict and Innovation 2 Holahan, & Amanson, 2007). Cognitive conflict involves parties getting into a heated debate about whose ideas are right versus wrong. This approach to conflict is best exemplified by the highly innovative company, Amazon.com, whose approach to conflict was recently highlighted in an article in The New York Times (Kantor & Streitfeld, 2015)… “At Amazon, workers are encouraged to tear apart one another’s ideas in meetings” “Of all of his [Jeff Bezos] management notions, perhaps the most distinctive is his belief that harmony is often overvalued in the workplace — that it can stifle honest critique and encourage polite praise for flawed ideas. Instead, Amazonians are instructed to “disagree and commit” (No. 13) — to rip into colleagues’ ideas, with feedback that can be blunt to the point of painful, before lining up behind a decision.” “We always want to arrive at the right answer,” said Tony Galbato, vice president for human resources, in an email statement. “It would certainly be much easier and socially cohesive to just compromise and not debate, but that may lead to the wrong decision.” Research on innovation and conflict backs the approach that Amazon embraces. Research shows that a collaborative style of conflict is more likely to lead to the adoption of impoverished outcomes (Badke-Schaub, Goldschmidt, & Meijer, 2010). Teams that adopt a collaborative style of conflict are less likely to raise new ideas and solutions – rather they spend more time discussing the same ideas over and over (Badke-Schaub, et al., 2010). Such a collaborative style of conflict does not result in a significant improvement of a group’s original ideas and concepts. On the other hand, teams produce better outcomes when different points of view and opinions are debated (Mooney, et al., 2007). Teams perform best when ideas and assumptions are directly challenged. Consistent with this reasoning, research on cohesiveness and group decision-making indicates that moderate amounts of conflict produce better results than when teams are overly cohesive or constantly at odds (De Dreu, 2006). Conflict and Innovation 3 The evidence suggests that when innovative outcomes are desired, it might be wise for entrepreneurs to foster an environment where cognitive conflict is encouraged. Cognitive Conflict and Affective Conflict. The problem with embracing cognitive conflict is that it leads to affective conflict. While cognitive conflict involves debates over ideas, affective conflict involves the personalization of issues at an emotional level – the feeling of being attacked (Mooney, et al., 2007). Or as described by workers at Amazon (Kantor & Streitfeld, 2015), heated conflict results in the following… “You walk out of a conference room and you’ll see a grown man covering his face” “Nearly every person I worked with, I saw cry at their desk.” For better or worse, cognitive conflict and affective conflict go hand-in-hand (Mooney, et al., 2007). It is difficult for people to engage in cognitive conflict without egos getting hurt in the process. While cognitive conflict leads to innovation, affective conflict can drain time, resources, and energy in ways that are not productive. Hurt feelings and tension can create workplace negativity and high levels of turnover (Wright & Bonett, 2007). As we see it, scholars with a background in interpersonal processes may be able to help design and test interventions, which can allow innovators to engage in cognitive conflict while quickly mitigating its negative effects. Potential Interventions Research emerging from the fields of social psychology, psychotherapy, and interpersonal communication focuses on developing interventions that can effectively mitigate the negative effects of engaging in heated arguments and disputes. These interventions are designed to protect relationships from the strains of negative affect using minimal amounts of Conflict and Innovation 4 time and resources (Finkel, Slotter, Luchies, Walton, & Gross, 2013). Applying these practices in an entrepreneurial setting may help individuals engage in cognitive conflict and reduce the negative outcomes that are likely to occur. We believe that developing and testing interventions may ultimately improve a team’s overall effectiveness when quality outcomes are required. In this paper, we identify two potential interventions designed to reduce negativity associated with conflict and discuss how these interventions may be used in an entrepreneurial context. We also provide an empirical test of one of the interventions proposed. Cognitive Reappraisal Intervention. In a marital context, research shows that having individuals engage in a brief, written reappraisal of conflict can protect marriages from the harms of conflict-related distress (Finkel et al., 2013). In this research, participants were asked to reflect on the conflict they encountered by using a third-party perspective. Specifically, individuals were asked to write about his or her conflict with a spouse through the eyes of a neutral observer: How might an outsider view the outcome of the conflict in a positive light? This written assessment was completed three times during a year taking a total of twenty-one minutes to complete. By viewing disputes from a neutral perspective, participants were able to emotionally reinterpret (see, Gross, 2002) what happened and mitigate the harm done. Given the effectiveness of this intervention in a marital context, where emotions typically run high, it is easy to imagine how a similar cognitive reappraisal intervention could be designed and tested for a workplace context where conflict may lead to negative affect. Such an intervention could be part of an ongoing task assigned to teams where cognitive and affective conflict occurs on a regular basis. Pause Intervention. In some situations, where feedback and conflict are particularly intense, the immediate remediation of negative affect may be called for. For instance, conflict Conflict and Innovation 5 may become heated during a threat assessment of a new business model as assumptions underlying value propositions, customer segments, costs estimates and potential revenue streams are debated. In such instances, it might be helpful to mitigate the negative feelings that are likely to arise. The Pause is an intervention designed for such contexts. The Pause is a technique developed by William Hernández based on his conflictresolution work in Ecuador (Focusing Ecuador, 2012). This intervention is based on the notion that it is important for an individual to focus on one’s body, feelings and their connection with others through collaborative activities. William Hernández and Soti Grafanaki recognized the potential of such practices for rebuilding a sense of community among team members and developed a set of practices to help reduce negative feelings that arise during conflict. In its most basic form the Pause intervention involves team members working together to pass an object among themselves while maintaining eye contact. While the Pause has been commonly used as a technique to reduce affective conflict in Latin America, little theoretical and empirical work has been offered in support of its effectiveness. We believe that there are several theoretical reasons why the Pause might be effective at reducing negative feelings among group members. To begin with, the Pause mimics many features of self-expansion activities – activities where individuals participate in interactive and novel tasks together (Aron & Aron, 1986; Aron, Norman, Aron, McKenna & Heyman, 2000). Due to their novel and interactive nature, selfexpansion activities release dopamine (see, for review, Aron, Lewandowski, Mashek & Aron, 2013) and individuals attribute this increase in positive affect to others (Aron & Aron, 1986; Aron et al., 2013; Aron et al., 2000). Conflict and Innovation 6 The Pause also involves mutual gaze, which is associated with the neuropeptide, oxytocin (Guastella, Mitchell, & Dadds, 2008). Oxytocin plays a critical role in human interaction – it helps alleviate distress and facilitates trust among individuals (see, for review Guastella et al., 2008; Nagasawa et al., 2015) even during times of interpersonal conflict (Ditzen et al., 2009). It is thought that mutual gaze induces an “oxytocin-mediated positive feedback loop” where prosocial feelings and behaviors increase levels of oxytocin, thereby resulting in more prosocial feelings and actions (Nagasawa et al., 2015, p. 334). While there are theoretical reasons to believe that the Pause activity may be effective at reducing negative affect through the release of dopamine and oxytocin, the technique’s effectiveness as not been tested. With this in mind, we conducted a pretest-posttest experiment to determine if the Pause can reduce negative feelings caused by conflict. Methods Overview. As part of a routine learning module on conflict, students in an undergraduate communication course participated in a twenty-minute, conflict-based activity known to create negative affect – a Public Goods Game (PGG). Levels of affective conflict (interpersonal tension) were observed. Students then participated in the Pause activity and another measure of affective conflict was taken. After the last round of data collection, students were debriefed and the class participated in a discussion on conflict resolution. The Pause activity, which is the focus of this research, took roughly three minutes to complete. Participants. Nineteen undergraduate students enrolled in a communication course at a large private university participated in this study. In accordance with Human Subjects Protocols, students were informed that data was being collected as part of a class activity. Students were told that they did not have to participate in the activity and/or the data collection and they would Conflict and Innovation 7 not be penalized for their nonparticipation nor rewarded for their cooperation. The vast majority of the participants were female (94.7%) and the median age was 21 (range 19 to 26). Affective Conflict Scales. Two modified versions of Mooney et al.’s (2007) Affective Conflict Scale were used in this study. The first scale, the Pre-Pause Affective Conflict Scale, was composed of four items designed to measure anger and tension among the participants (see, Appendix A). These items were modified to fit the context of a classroom setting rather than a work team. The participants were asked to reflect on their experience right after participating in the conflict activity (the PGG). The four items were assessed using a 7-point scale where “1” represented strongly disagree and “7” represented strongly agree. The four items had a high level of reliability (alpha = .85, M = 4.0, SD = 1.92). The second scale, a Post-Pause Affective Conflict Scale, consisted of four items designed to measure affective conflict after the Pause activity (see, Appendix B). The items were slightly rewritten to take into account that the participants were completing the scale for a second time. Again, the four items were assessed using a 7-point scale where “1” represented strongly disagree and “7” represented strongly agree. This scale also had high levels of reliability (alpha = .89, M = 1.65, SD = 1.14). Public Goods Game. As part of a normal learning module on conflict, a version of a Public Goods Game was played in class. Essentially, students working in teams could act cooperatively as a whole or defect and act in terms of their self-interest. The outcomes of their choices impacted the group as a whole. When all teams cooperated, all teams were rewarded. If one team defected, the defecting team would win while cooperating teams were penalized. When all teams defected, all teams were punished (a more detailed description of this activity can be found at Conflict and Innovation 8 http://www.univie.ac.at/virtuallabs/PublicGoods/index.html#pgg). Ten rounds of the PGG were played giving students ample opportunity to cooperate and defect. Pause Intervention. The Pause Intervention is simple. It stems from work by William Hernandez and Soti Grananaki who developed a technique to help people focus on one's body and call greater attention to emotional states as they unfold (Focusing Ecuador, 2012). Team members gather standing in a circle and await instructions. A leader explains the task: Pass the balloon (or any object on hand, though balloons work best) to the person next to him or her. Eye contact must be maintained at all times when passing or receiving the balloon. At first, the object is passed at a moderate pace, but gradually the leader increases the speed by saying "faster" throughout the initial round. Eventually, the leader stops the round and asks everyone to take a short break (roughly ten seconds). The second round begins the same as the first with individuals passing the object while maintaining eye contact. This time however, the leader requests the participants to pass the balloon more slowly, gradually slowing the process until each person has possession of the balloon for about ten seconds. Once everyone has had at least two opportunities to hold the balloon, the second round ends. Procedures. During a lecture on conflict, the first author asked students to participate in an activity designed to simulate the negative emotions experienced when disagreements occur. A PGG activity was used to simulate conflict as part of a normal instructional exercise. Immediately after the PGG activity, students completed a survey consisting of the Pre-Pause Affective Conflict Scale. Following the completion of the survey students participated in the Pause Activity. Immediately afterward, the students completed the Post-Pause Affective Conflict Scale. Students were then debriefed on the exercise and participated in a discussion on conflict. Results Conflict and Innovation 9 To determine if there was a difference in affective conflict after the Pause Intervention, a paired t-test was conducted on the Pre- and Post-Pause Affective Conflict scores. The results indicate that there was a reduction of interpersonal tension after participating in the intervention, t(18) = -6.23, p. < .001). Discussion Innovation requires rapid testing and modification of assumptions, value propositions, market segments, etc. Innovation is most likely to occur when ideas are openly debated and challenged through cognitive conflict (Mooney et al., 2007). Such a confrontational style of conflict, however, leads to affective conflict – hurt egos and interpersonal tension (Mooney et al., 2007). In this research, we present two possible interventions that may be helpful when trying to alleviate the problems that occur when conflict is personalized. Specifically, we discuss how a written, cognitive reappraisal intervention could help reduce the impact of negative affect associate with conflict, given the protective function this technique provides couples in a marital context (Finkel, et al., 2013). We also discussed and conducted a pilot-test of the Pause Intervention – a simple activity where group members participate in a collaborative task involving prolonged eye contact. The results of our study show that the Pause Intervention was effective at reducing negative feelings towards group members in a very brief period of time (3 minutes). Comparing the level of affective conflict observed here to the level of negative affect across 94 workplace teams (Mooney et al., 2007) reveals that our simulated conflict game (PGG) created fairly realistic levels of interpersonal tension. Our observed level of affective conflict was in the top 99% of the affective conflict scores reported by Mooney and his associates, z = Conflict and Innovation 10 2.62 (assuming a normal distribution). After the Pause Intervention, however, the level of Affective Conflict observed fell dramatically – to the bottom quartile of the scores reported by Mooney at el., z = -.72. In other words, affective scores dropped from the high point observed in past research to relatively low levels of interpersonal tension. In fact, we observed a 58% drop in negative affect in three minutes. We believe that the Pause Intervention is effective at reducing negative affect because it involves both a self-expansion activity (Aron & Aron, 1986; Aron et al., 2000) and prolonged eye contact, which are associated with increased levels of dopamine (Aron et al., 2013) and oxytocin (Guastella et al., 2008). Innovation is critical for economic and social growth. We hope that a deeper understanding of the process of innovation and the challenges it presents will encourage scholars to find solutions that help facilitate innovative outcomes. In light of the research presented here, we hope to identify and test a wide range of interventions that can be used to quickly help teams come together after heated disputes. Finding a diverse set of strategies for overcoming the negative side effects of cognitive conflict will be of use to entrepreneurial educators and practitioners across a wide range of contexts. Finally, as our knowledge about interpersonal neurobiology (see, Cozolino, 2014) continues to grow, we hope this knowledge will be used in ways that help advance entrepreneurial practices. Conflict and Innovation 11 Appendix A Pre-Pause Affective Conflict Scale Mooney, Holahan and Amason’s (2007) affective conflict scale was modified to fit the context of engaging in conflict in a classroom setting. The prompt question and items are provided below (alpha = .85). Reflecting on the conflict exercise, please respond using the scale below: • • • • I was upset during the conflict exercise. I felt that there were personal clashes during the conflict exercise. There was tension in class because of the conflict exercise. There was a sense of rivalry during the conflict exercise. Conflict and Innovation 12 Appendix B Post-Pause Affective Conflict Scale Mooney, Holahan and Amason’s (2007) affective conflict scale was modified to fit the context of having engaged in conflict and then completed the Pause activity. The prompt question and items are provided below (alpha = .89). Reflecting on how you feel now, please respond to the items below: • • • • I am still upset about the conflict exercise. I still feel that there are personal clashes due to the conflict exercise. There is still tension in class because of the conflict exercise. There is still a sense of rivalry because of the conflict exercise. Conflict and Innovation 13 References Aron, A., & Aron, E. N. (1986). Love and the Expansion of Self: Understanding Attraction and Satisfaction. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corp/Harper & Row Publishers. Aron, A., Lewandowski Jr, G. W., Mashek, D., & Aron, E. N. (2013). The self-expansion model of motivation and cognition in close relationships. The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships, 90-115. Aron, A., Norman, C. C., Aron, E. N., McKenna, C., & Heyman, R. E. (2000). Couples' shared participation in novel and arousing activities and experienced relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 273. Badke‐Schaub, P., Goldschmidt, G., & Meijer, M. (2010). How does cognitive conflict in design teams support the development of creative ideas?. Creativity and Innovation Management, 19(2), 119-133. Cozolino, L. (2014). The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Social Brain (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). New York: WW Norton & Company. De Dreu, C. K. (2006). When too little or too much hurts: Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between task conflict and innovation in teams. Journal of Management, 32(1), 83-107. Ditzen, B., Schaer, M., Gabriel, B., Bodenmann, G., Ehlert, U., & Heinrichs, M. (2009). Intranasal oxytocin increases positive communication and reduces cortisol levels during couple conflict. Biological Psychiatry, 65(9), 728-731. Finkel, E. J., Slotter, E. B., Luchies, L. B., Walton, G. M., & Gross, J. J. (2013). A brief intervention to promote conflict reappraisal preserves marital quality over time. Psychological Science, 24, 1595-1601. Focusing Ecuador. (2012, August 2). Learning to listen with focusing by way of the pause. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UcqBfleQuOo. Guastella, A. J., Mitchell, P. B., & Dadds, M. R. (2008). Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biological Psychiatry, 63(1), 3-5. Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(03), 281-291. Kantor, J., & Streitfeld, D. (2015, August 15). Inside Amazon: Wrestling big ideas in a bruising workplace. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://nyti.ms/1ISY0xv Conflict and Innovation 14 Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Goldsby, M. G. (2011). Innovation Acceleration: Transforming Organizational Thinking. New York: Pearson Higher Ed. Mooney, A. C., Holahan, P. J., & Amason, A. C. (2007). Don't take it personally: Exploring cognitive conflict as a mediator of affective conflict. Journal of Management Studies, 44(5), 733-758. Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., & Cornwall, J. R. (2013). Entrepreneurship Programs and the Modern University. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. Nagasawa, M., Mitsui, S., En, S., Ohtani, N., Ohta, M., Sakuma, Y., Onaka, T., & Kikusui, T. (2015). Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science, 348(6232), 333-336. Wright, T. A., & Bonett, D. G. (2007). Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as nonadditive predictors of workplace turnover. Journal of Management, 33(2), 141-160.