Common Bond - The New York Landmarks

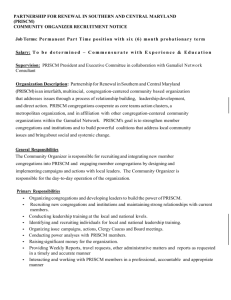

advertisement