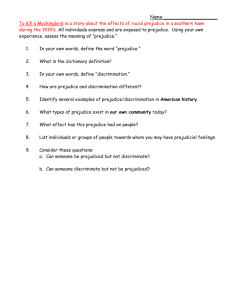

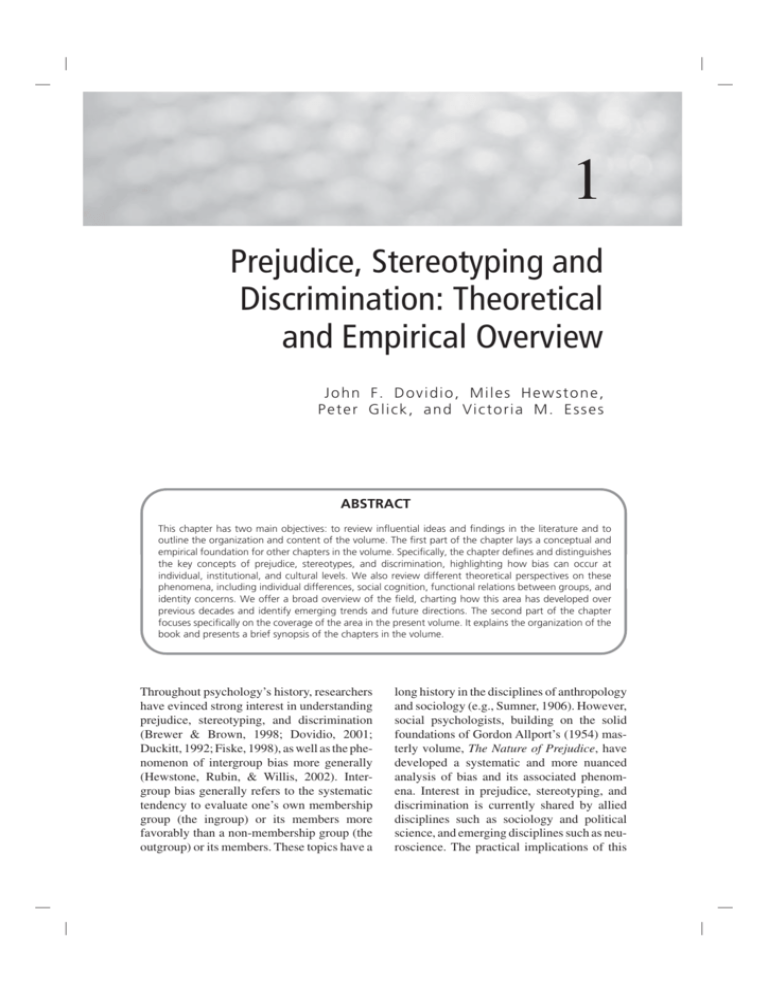

Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination

advertisement