building hope with real faith - Resources for American Christianity

advertisement

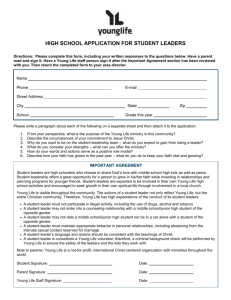

BUILDING HOPE WITH REAL FAITH: ANNE STREATY WIMBERLY AND AFRICAN-AMERICAN YOUTH MINISTRY by John M. Mulder No one underestimates the difficulty of youth ministry, especially among Black young people whose lives are drastically affected by not only all the toxic effects of American culture but also racism and poverty. Least likely to ignore the magnitude of the challenge is Dr. Anne E. Streaty Wimberly, the nation’s leading Black Christian educator. “It will be extremely difficult to make a helpful and lasting impact on our youth, their movement toward a hopeful future, and their wearing the mantle of hopebuilder,” she writes. “But we must make every effort to do so”1 Dr. Wimberly is equal parts realist and idealist—unflinchingly clear about the dangers confronted by Black youth and passionately committed to her conviction Dr. Anne Streaty Wimberly that the Christian faith can and should be “made real” to them. Now professor of Christian education emerita at the Interdenominational Theological Center (ITC) in Atlanta, she is also a prodigious researcher, prolific writer, and probing teacher. She is currently the director of two Lilly-funded programs: the Youth HopeBuilders Academy and Vision Quest: A Study of Efforts, Challenges, and Needs of Youth Ministry Leaders in Black Congregations; and she served as principal 1 Anne Streaty Wimberly, Keep It Real: Working with Today’s Black Youth (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2005), xviii. “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ investigator of the Lilly-funded Faith Journey: Partnership in Parish Ministry Formation Program. All three programs are based at the Interdenominational Theological Center, a consortium of six seminaries sponsored by historically Black denominations. She has published 10 books and a multitude of articles and reviews. In addition to her full-time teaching (at least until her supposed retirement from ITC), she has made scores of lectures and presentations in church and academic settings throughout the United States and Africa. She was the first Black president of the Association of Professors and Researchers in Religious Education and the second Black president in the 100-year history of the Religious Education Association. And — she’s a musician. Trained initially in music education, she plays the organ and devotes her energies to organizations such as the Atlanta Opera and Voices for Georgia’s Children, where she has served on their boards. Her teaching and scholarship range across virtually all phases of Christian education and congregational ministry. But her passion — and her vocation — is youth and family ministry in Black churches, especially the Lilly-supported Youth and Family Convocations and the Youth Hope-Builders Academy, both held annually at the Interdenominational Theological Center. Dr. Wimberly came to the focus of her ministry and teaching by listening to her students. “I asked them, ‘What’s the most important issue confronting black churches today?’ The answer was crystal clear – youth and families.” The first result of this focus was the Interdenominational Youth and Family Convocation. It started with 173 participants in 1994 and now draws more than 1,000. The second result was the Youth Hope-Builders Academy for high school black youth. Dr. Wimberly and ITC received a planning grant in 2000 and launched the Youth Hope-Builders Academy in 2002. 276 youth have been through the program. “And 99 percent who have graduated from high school have entered undergraduates studies,” she notes proudly. Eighty of these young people have gone to college, and they have attended 52 different colleges and universities. But the origins of her passion and vocation are more complex and deeply rooted in her history. “I was called to ministry very early,” she says in a soft voice. “I was the daughter of a minister, but I had no role models of women in ministry. So I pushed the call into the recesses of my mind.” In the church of her childhood, the congregation had a ritual of calling forth young people. Each youth’s individual gifts were named in the practice of the laying on of hands. “I was told my gifts were music and teaching.” Page 2 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ So she went to college, majored in music education at Ohio State University, pursued coursework for a doctorate in music at Boston University, and taught in public schools and colleges for more than 20 years. She received her Ph.D. in educational leadership from Georgia State University in 1981 and taught for several years in colleges and universities. “I always have had a love for young people,” she says, “from kindergarten to high school to higher education.” “But the call wouldn’t go away,” she recalls, so she finally enrolled at Garrett Evangelical Theological Seminary and received her Master of Theological Studies (MTS) in 1993. Garrett honored her as a distinguished alumna in 2009. Along the way she met Edward P. Wimberly, a professor of pastoral care and counseling. “We always wanted children,” she recalls. “I lost four children, and I almost lost my life. It was a very difficult time for us. I kept yelling to God, ‘What’s going on?’ And then I had three dreams. In the first one, there was smothering blackness, and through the darkness came an illumined hand. A voice said, ‘This is the hand of God that will lead you.’ In the second one, I saw our baby daughter in heaven. She was delivered in the eighth month of my pregnancy and died two days after birth. And the third one was opaque. All I heard was a voice saying, ‘You shall have many more children than you can have biologically.’” “That was it,” she says. “I knew what I had to do. So you see, everything I’m doing has a very personal dimension, and youth ministry is the heart of my call to ministry. The current generation of high school youth are like my grandchildren. When the students call me ‘Grandma Anne,’ my heart sings.” Dr. Wimberly has a definite relational pedagogy behind her approach to youth ministry in Black Churches and as the focus of the Youth Hope-Builders Academy. It consists of three connecting elements: Realism about the life stories of Black youth. The role of community understood as “the village.” Christian identity and leadership formed and lived, especially expressed in hope and love. “We have to start with Black youth as they are, and that means beginning both with their giftedness and with their experiences of discrimination, racism, health issues, peer pressure, mis-education, poverty, underemployment, unemployment — all the issues that affect their lives and the lives of their families,” she argues. “But all of those are complicated even more today by the breakup of the village — the families and extended families, the institutions such as the Black church, and the customs that shaped individual and social life. These helped form character Page 3 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ and community for youth.” She argues that “youth desperately need the support of the community.” The substance of that support is Christian identity, expressed in hope and love. “I truly believe hope and love can be instilled,” she declares. “These youth can realize, ‘I can really make a difference. I can make hope come alive.’” “The key,” she stresses, “is identity and Christian identity. They see themselves as children of God. They realize unapologetically and unashamedly they are Black — African American, African, Caribbean. God loves them as they are. They find a calling and discover they are leaders.” The program of the Youth Hope-Builders Academy is a multi-faceted educational experience designed to meet those three elements, focusing on the youth themselves and those who care for them. The program for youth involves a three-week, residential summer program. The participants are teenagers, ranging from 13 to 17 years of age. Most live in Georgia, and the remainder come from other southeastern states. The majority belong to historically black churches; about 40 percent of the total are Baptist with the rest coming from a variety of denominations. The first two weeks are spent at the Lodge at Simpsonwood, a retreat center in Norcross, Georgia, followed by a week of residence on campus at the Interdenominational Theological Center. That third week consists of peer mentoring and service work in the Atlanta area, though students have also participated in renewal work in New Orleans following the Katrina hurricane. The application process is rigorous. Students must have a minimum cumulative grade point average of 2.5 and recommendations from a pastor, teacher, a Youth Hope-Builders graduate or staff, or other school/community leaders. Every applicant must submit a written statement of purpose and be interviewed by Academy leaders. Currently, only 28 are admitted each year. “My greatest regret,” Dr. Wimberly notes, “is the ones we turn away. How can we choose when so many need it? And how can we reach those beyond the church? These are major, major issues.” The program itself includes: Exploration of Black youth issues. Using curricular materials developed in the Youth Hope-Builders Academy, youth engage in open dialogue and analyze the very real, everyday concerns they encounter, their feelings about those issues, and the relationship of their experiences of difficult issues to hope and Christian theology and practices. Page 4 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ Exploration of Christian identity and vocation. Youth explore theologically their identities as human beings, Black people, and Christians as well as their gifts and opportunities for expressing the gifts in pastoral ministry, church leadership, and other vocations. “Heart to Heart” Mentoring Groups. These provide formal and informal “sacred spaces” with caring, experienced mentors. Youth reflect on and process their experiences, receive guidance, and develop a theological focus for “meaning making.” Arts and Worship Experiences. Every day begins with worship, and the services expose youth to diverse Pan-African styles of worship and offer them the opportunity to practice leadership roles in worship. Students are also encouraged to express themselves through music, liturgical dance/movement, and the visual arts. Cultural sensitivity and service learning endeavors. Through printed material, films, and video-conferencing with students in Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere, students are exposed to their heritage and its value. They see their connections with Black people in the African diaspora. They are also inspired with a positive sense of responsibility for leadership and service with people in need, as well as those who differ from them. Social and recreational activities. These focus on building healthy relationships among the youth, helping them to learn and grow individually and collectively, and finding helpful ways of dealing with differing opinions and conflict. Following the three-week summer program, there are two important follow-up “Village Forums” for the students and the adults in their lives. One is held in February in conjunction with the annual Youth and Family Convocation. The next is an April Ceremony of Graduation, in which the current Youth Hope-Builders Academy students “pass the torch” of the Academy from themselves to the new class of youth. At these forums, students present reports on their church or community service projects and maintain contact with one another and the context from which they come. At the graduation ceremony, Dr. Wimberly says, “parents and grandparents talk about their expectations of their children. We release the students with prayer and those expectations. It’s always a wonderful family day.” “Our goal is re-villaging,” Dr. Wimberly says. “We are village-oriented. We don’t take them away but we put them back into the communities they came from. But Page 5 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ they go back with a sense of identity as Black and Christian. They go back with a calling. They go back with strength.” According to the youth, the most powerful experience in the residential program is the “Heart-to-Heart” mentoring groups. One student declared, “I can say what’s really going on in my life and be heard.” Another said, “They always say guys are not supposed to cry. And, I came saying that I wasn’t going to cry. But there’s something about what happens in heart-to-heart that gets to you. I cried and it was okay. I don’t believe anymore what they always say about guys not crying.” According to another student, “Heart to Heart” was my best experience in this community. We talked about solutions to problems in my life.” Another concluded, “I was able to open up and be vulnerable to constructive criticism and praise. It helped me realize errors of mine to fix.” Another especially vital part of the program is the focus on the arts and worship. Regarding the arts, one student stated, “I don’t sing. I mean, I haven’t sung in any choir before. Even though I probably won’t sing in a choir after I leave YHBA, it wasn’t a bad thing, doing it with everybody else in YHBA. Honestly, I enjoyed it.” Another admitted, “I didn’t want to dance at all. But, I found out that I really like it and I’m good at it. I discovered a new me.” In addition, worship gives them a previously unknown opportunity for expression and leadership. Among the students’ responses were these: “I got to exhibit my gifts and talents.” “Worship built us up as Jesus’ followers.” “Worship gave a constant reminder of the price paid for our salvation.” “We were allowed to share defeats/victories, hurts/joys, testimonies.” “Worship kept our minds and hearts centered on God and God’s purposes for our lives as we journey through life.” An equally powerful, if not transformative, experience is the third week in which students do both service projects and provide peer mentoring for middle school Black students. These middle school youth focus on two things, Dr. Wimberly says. “First, they have to articulate their own Christian identity. Second, they have to deal with real issues — the critical and often painful ones that Black youth experience every day and every week.” Page 6 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ As an example, she described a group of high school mentors and middle school mentees in which one student engaged in role-playing. The individual’s experience was being ridiculed. The issues were self-esteem, body image, and color. The group then broke into small groups, and the question was: “How does that feel?” Eventually the discussion revolved around the question, “What does it mean to be a child of God?” Dr. Wimberly says, “It was very powerful. It almost brought you to tears. These young people began to realize, ‘You’re more than someone says about you because you’re God’s child.’” And, she adds, “It not only affirmed the mentee but also the mentor who spoke the words of affirmation and was affirmed by saying them. Affirmation always works both ways. It’s interrelated.” As one high school youth declared, “I can’t tell my mentee what I won’t do myself, so I’ve got to do the right thing.” Another said, “I wanted to be a mentor. Being responsible for someone else means being responsible yourself.” The result of the peer mentoring and service work is what Dr. Wimberly hopes for. Students see themselves as Black and Christian and know they have worth because they are children of God. Students have responded to the Youth HopeBuilders Academy in these words: “YHBA made me feel stronger about what I think is important. As a Christian, I know there will be times when I will be discriminated against. I will have to stand firm on my beliefs, and may be punished for them.” “I know who and whose I am.” “My confidence level went up. I now have pride in who I am.” “I have a new appreciation for who and whose I am. I am young, Black, gifted, God-fearing, loving, and kind.” “I have changed the way I view myself in society. wonderfully made.” I am fearfully and “I have gifts that I’ve used in the past, but not willingly, because I lacked confidence. I am more confident now.” “I saw myself in sisters and brothers in Africa.” “YHBA made me want to know more about my homeland.” “I know now that there are many ways one can serve God. I know I can help others.” Page 7 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ The parents/guardians of the youth see the differences immediately. Here are samples of their feedback: “He is more helpful.” “I see a young lady who has overcome being shy. She has blossomed.” “We are communicating more as a family about church and how we can make a difference.” “My son is more vocal about declaring his faith.” “My son’s awareness of the needs of others and connection to the community has truly increased. He has returned to us with a more directed path. He is less concerned with what his peers think, and tries to get them to consider a new way of thinking that would be pleasing to God.” “I see major differences in my child’s ability to discern and think more carefully about choices. The YHBA program was a God-send in our lives. Our son is more aware of his responsibilities as a leader, son, and Black youth.” The reciprocal and mutual affirmation of identity and worth has had an impact on the villagers themselves — the family members, caregivers, leaders, churches, and teachers involved in the Youth Hope-Builders Academy and the Interdenominational Youth and Family Convocation. The result is a new awareness and renewal of the families, churches, and leaders in Black churches. Some of the students return home and ask to lead worship. Others start new programs in their churches. Some introduce dance or other arts into their congregations’ worship and life. Others insist on a role for youth in the leadership of the church itself. The leaders are changed as well. After participating in the Youth Hope-Builders Academy, one leader reflected, “I learned a lot about youth. But I learned just as much about myself — prayer, patience, and humility. I have seen how God gives you the capacity to love unconditionally and reach young people who are the most in need of this love.” Another said, “This is a unique program that empowers and transforms the lives of not only youth, but adults who are involved. Being here helped me to recognize the significance and value of the village in the growth and development of every youth. It has also helped me realize that my story is not mine alone.” Another leader summed up the heart of the Youth HopeBuilders Academy: “I learned that youth long to be hugged, affirmed, and embraced even when they put a ‘hard face’ on.” Page 8 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ Of course, there are problems and challenges. One is financial. Despite the generous funding from Lilly Endowment, the Youth Hope-Builders Academy and the Interdenominational Youth and Family are chronically short of funds. Dr. Wimberly and her colleagues must do additional fundraising, seeking donated money, materials, and services. Another is what Dr. Wimberly calls the “insularity” of congregations. Some resist adopting ideas that come from outside their congregation or outside their denomination. Another is the challenge of replicating and spreading the model of the Academy and the Convocation to other areas of the country and across denominations. Another is the problem of families and churches supporting the vocational aspirations that students find in the programs of the Academy and the Convocation. Particularly when students return and declare they want to be a minister or church leader, parents sometimes object. Dr. Wimberly says she might hear, “My child is not going to be a minister. He’s going to be a biologist.” She is concerned about this conflict between parental dreams and a call to Christian ministry. “I don’t know what to do about that,” she says. “How do you help these young people and their parents honor what they’ve learned?” Nevertheless, Dr. Wimberly continues her advocacy on behalf of Black youth and ministry with them. Her efforts have attracted attention from churches across the United States and in the West Indies, South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria. Her current research project also focuses on what constitutes excellence in Black youth ministry. Very little is known about what is happening, she says. “What works? What doesn’t work? Why? And why not?” Dr. Wimberly is convinced there are certain pedagogical principles that shape effective ministry with Black youth. Relationships. “It always builds on the other person — the youth in this case and their families and where they are coming from. It never starts with what I know and what I want you to learn.” Realism. “We need to recognize — and respect — the issues that youth and their families actually experience and the questions and longings they express. They come from the reality of their homes, schools, communities, and churches, and they range from how does someone deal with a bully to what is the calling and the reign of God.” Page 9 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ Evaluation. “We learn by hearing from and listening to the youth and their families. They have to write it down, and they learn something by doing that. But it also demands conversation, testing, and experimenting.” Dr. Wimberly recognizes but rejects the possibility of taking the model of the Youth Hope-Builders Academy and changing it to a focus on Black identity without a specific Christian emphasis. “I don’t think it would be right, appropriate, or good to change the Christian identity of the Academy,” she insists. “However, we have to deal with issues as they are. We need to be where young people are — such as community centers or athletic centers.” As an example of meeting Black youths directly, she cited the example of a church that organized teams of men to talk with Black youth as they waited for school buses. Problems of violence and crime soon dissipated. “That’s an example of how life can be different through relationships,” she says. “The Christian walk is a relational walk.” For Dr. Wimberly, the goal of those relationships with Black youth is Hope (with a capital “H”). In her book, Keep It Real: Working with Today’s Black Youth, the quotes of youth in the Academy put it this way: “Hope is believing there is a higher power that you can turn to in times of need.” “Hope is the will to keep faith in something and believe that everything will turn out okay. It is belief that you can come out of any hardship. When you have faith, you believe that something can be accomplished even though it seems out of reach or impossible. Hope is faith, faith is believing, believing is achieving, and achieving is succeeding.” “Hope is the presence of courage to believe. It is knowing that you can reach a goal. Hope is having faith in something you might not have any control over; and even though you might not know how it is going to turn out in the end, you know it will turn out for the best. Hope is believing you can make a difference.” “Hope means always believing in God and letting God take control; it is trust! With hope, you put it all in God’s hands and trust and believe in whatever the outcome. It is a way back to God in a trying situation.” “Hope means trusting yourself. It is having faith in me.”2 2 Ibid., 121. Page 10 of 11 “Building Hope with Real Faith: Anne Streaty Wimberly and African-American Youth Ministry” from the website Resources for American Christianity http://www.resourcingchristianity.org/ If Hope is the goal, the message for inspiring Hope is Love. “I live 24/7 with them,” Dr. Wimberly says about the Youth Hope-Builders Academy. “I’m constantly walking around and talking to them. I’m hugging them and saying to them, ‘I love you.’” “You are loved,” she says. “That’s the most important thing they learn. And that’s true for everyone. In a world where people communicate at a distance, in the midst of busyness, they often don’t hear something endearing.” “Sometimes a student comes back and asks, ‘Is Grandma here? I just want to hear she loves me,’” Dr. Wimberly recalls. “They need to hear that they are not just loved by me but loved by God. Isn’t that what we most want to hear — no matter what trouble we’re in?” Dr. Wimberly was moved by the story of the Haitian woman who survived seven days amidst the rubble of the cathedral in Port au Prince. “The rescuers finally heard somebody,” she says, “and they heard her singing! That’s how they found her. I’ve told that story many times. It’s about a love that sings, a hope that sings.” “That story impels us and inspires us to ask how we can sing in the midst of the rubble of life,” she concludes. “Let us sing!” For more information about the Youth Hope Builders Academy: On the internet, go to http://www.youthhopebuilders.org. By email, write info@youthhopebuilders.org. By regular mail, write Youth Hope-Builders Academy, Interdenominational Theological Center, 700 Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, Atlanta, Georgia 30314. By phone: call (404) 527-7700, press 1, ext. 5559. Page 11 of 11