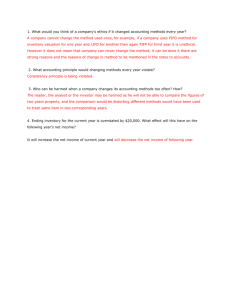

Working Capital Management

advertisement