SGIR - Brummer - GPM and PHT - EISA

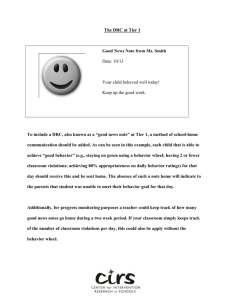

advertisement