Market Orientation and Consumers' Orientation Revisited

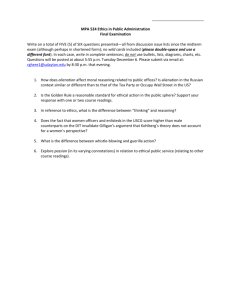

advertisement