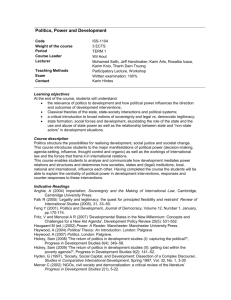

What Do We Get from a 'Social Contract'

advertisement