Beyond grapheme-phoneme correspondences

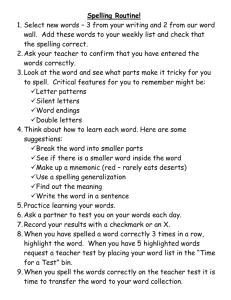

advertisement

Beyond the first steps in reading and spelling Peter Bryant First thoughts Orthographies are only partly systems for encoding the sounds of oral language They are also systems for representing deeper linguistic distinctions, like the “-ed” spelling for past tense inflections Perhaps it is wrong and dangerous for psychologists and teachers to ignore these deeper regularities, Perhaps it would be quite easy to encourage children to be interested in these regularities and to learn about them The view that children are taught GPCs and then learn everything else for themselves Most current models of reading and spelling at word level argue that children should first acquire the basic phonological/alphabetic rules-grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs) with the help of teachers, and then can work out the rest of the system for themselves Current approaches to teaching in the UK adopt this approach too: teach children about phonology and the alphabet and the children will take care of the rest of the learning for themselves Spelling rules beyond the GPCs are largely ignored by theorists and teachers alike Spelling rules beyond alphabetic correspondences (GPC) There are at least two kinds of spelling rule beyond GPCs: Conditional rules, like: the split digraph (hop vs hope), other digraphs, the /k/ ending Morphemic spelling rules, like the spelling for the past tense ending “ed”: kissed, rolled, wanted Nunes T. & Bryant. P. (2009) Children’s Reading & Spelling: beyond the first steps Wiley-Blackwell Morphemic spelling rules in many languages (French, English, Greek, Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic) when the same sound is spelled in different ways for morphemic reasons fox education socks magician when different sounds are spelled in the same way for morphemic reasons kissed rolled cats heal dogs health waited when spelling represents silent morphemes la maison les maisons Morphemic spelling rules exist…….. But do people actually use these rules to spell such words correctly? The alternative is that they learn the specific spellings for each word (word-specific learning) Three parts to the talk Despite lack of teaching, children construct morphemic rules for themselves Actually that’s not right: many children and adults don’t construct morphemic rules for themselves You can teach morphemic rules to all children English children construct morphemic rules for themselves: spelling the “-ed” regular past verb ending Spelling the endings of /d/ and /t/ non-verbs /d/ ending /t/ ending bird cold field gold ground belt except next paint soft Nunes, Bryant & Bindman Mean correct phonetic spellings of non-verbs ending in /d/ or /t/ (out of 10) in 3 sessions over a period of 21 months 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 start 7m later 21m later N=297 6yr5m 7yr5m Nunes, Bryant & Bindman 8yr7m Spelling the endings of regular past verbs with /d/ and /t/ inflections /d/ ending /t/ ending called covered filled killed opened dressed kissed laughed learned stopped Mean correct “-ed” spellings (out of 10) in 3 sessions over a period of 21 months 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 start 7m later 21m later 6yr5m 7yr5m Nunes, Bryant & Bindman 8yr7m N=297 Phonetic endings instead of the correct “-ed” ending most of the mistakes with regular verb endings are phonetic transcriptions: e.g. “kist” for “kissed” these inappropriate phonetic transcriptions are made even by some 10 year olds Number of incorrect phonetic transcriptions of regular verb endings 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 6 7 8 9 10 Generalisations and overgeneralisations of the “-ed” ending many children put “-eds” on the ends of irregular past verbs (sleped) (71%), and also of non-verbs (sofed, necsed) (59%) as well as of regular past verbs (kissed) the generalisation to irregular verbs is incorrect but grammatically appropriate the generalisation to non-verbs is incorrect and inappropriate grammatically Nunes, Bryant & Bindman Incorrect generalisations of the “ed” ending to irregular verbs “sleped” & to non-verbs “necsed” 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 s yr 10 rs 8y rs to nonverbs to irreg vbs 6y at first the children make the two types of generalisation roughly equally but by 8 yrs they make many more generalisations to irregular verbs than to non-verbs Nunes, Bryant & Bindman /d/ and /t/ endings are spelled as “d” and “t” grapheme-phoneme rule /d/ and /t/ endings are sometimes spelled as “d” and “t” and sometimes as “ed” “ed” endings are for past verbs: “d” and “t” endings are for everything else extension of grapheme-phoneme rule morpho-phonemic rule Greek children construct morphemic rules for themselves: spelling stems and affixes A study of Greek children’s learning of how to spell vowel sounds in inflections and in stems Greek is a highly regular orthography as far as reading is concerned Spelling is less predictable because there are very few vowel sounds in Greek, and there is more than one way of spelling three of the vowels e.g. /i/ is represented by: ι , η , ει, οι /o/ is represented by: ο , ω /e/ is represented by: ε , αι There is no rule for which spelling to adopt for the vowels in stems, but in inflections the spelling is determined morphemically Sound in real word stems Sound in real Sound in pseudoword inflections word inflections τόπι(ball) νερό(water) βεσό /o/sound φωνή(voice) μιλάμε(we talk) δίνω(I give) λιβώ παιδί(child) θότι πόλη(town) ρέκη /i/ sound μήλο(apple) μιλάμε (we talk) δίνω (I give) φιλώ (I kiss) ρίχνομαι (I fly into) τόπι (ball) παιδί (child) βόδι (ox) νησί (island) θότι νεπί σόβι κιφί ψήνει (s/he cooks) μήλο (apple) κήποι (gardens) νησί (island) ζώνη (waistband) πόλη (town) θέση (place/seat) φωνή (voice) λόχη κόση ρέκη βοπή κλείνομαι (I am shut up in) θείοι (uncles) δείχνουμε (we show) πειράζει (s/he teases) ψήνει (s/he cooks) δένει (s/he ties) πειράζει (s/he teases) κοιτάζει (s/he looks at) πέφει γίβει σιφάγει διπάγει κοιμάμαι (I sleep) τοίχοι (walls) κοιτάζει (s/he looks at) ανοίγουμε (we open) τοίχοι (walls) θείοι (uncles) κήποι (gardens) καιροί (days/times) λίροι μίοι νίγοι σεποί 32 30 28 26 24 22 20 18 Real Word Stems 16 Real Word Inflections 14 Pseudoword Inflections 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Session A (Mean age: 6y10m) Session B (Mean age: 7y6m) Session C (Mean age: 8y6m) Chliounaki & Bryant (2007) Number of children (out of 90) significantly above chance level (+) or not (-) with real word inflections (RW) and pseudo-word inflections (PW) Session A Session B Session C Significantly above chance level on 3 pseudowords RW-PW- 35 10 RW+PW- 30 23 17 RW-PW+ 0 1 0 RW+PW+ 25 56 70 Session A 27.8% Session C 77.8% Chance level .375: 18+/32 above chance level Session A Real word inflections .434** Session B Real word inflections -.036 Pseudoword inflections Pseudoword inflections Session A Real word inflections .434** Session B Real word inflections -.036 Pseudoword inflections Pseudoword inflections Chliounaki & Bryant (2007) Session B Real word inflections .390** Session C Real word inflections -.010 Pseudoword inflections Pseudoword inflections Session B Real word inflections .390** Session C Real word inflections -.010 Pseudoword inflections Pseudoword inflections Chliounaki & Bryant (2007) Session B Real word stems .253 Session C Real word stems .197 Pseudoword inflections Pseudoword inflections Chliounaki & Bryant, 2007 Session A Real word stems .146 Session B Real word stems .172 Pseudoword inflections Pseudoword inflections Chliounaki & Bryant, 2007 Conclusions from the Chliounaki & Bryant study Children get to spell inflections correctly in real words before pseudowords However in their first two years at school most children learn the morphemic spelling rules for inflections pretty well Cross-lagged correlations between real and pseudoword spelling of inflections suggest a causal connection: It is that word-specific learning lays the basis for inferring the morphemic spelling rules At this stage we were confident that pretty nearly all children constructed the basic morphemic spelling rules by themselves Many English people don’t construct some of the morphemic spelling rules for themselves Do children learn the morphemic spelling rule about the English plural ending? In English one of the most basic morphemic spelling rules is that the last sound in buns and dogs is /z/ but it is spelled as “s” because “s” is the spelling for the plural morpheme in English but there is also a non-morphemic, frequency rule: which can account for the spelling of many words ending in /z/. In almost every word that ends in a /z/ which is preceded by a consonant, the /z/ ending is spelled as “s”: dogs, bastards Exceptions are rare words : adze, bronze The children saw two ________ on a plate The children saw two ________ on a plate The children saw two beans on a plate The children saw two bees on a plate The children saw two pleens on a plate The children saw two prees on a plate Children’s “-s” spellings of the /z/ sound at the end of plural words and pseudo-words (%) 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 beans bees Real plural words pleens prees Plural pseudo-words Kemp & Bryant, 2003 Adults’ “-s” spellings of the /z/ sound at the end of plural pseudo-words 100 90 Educational Levels 80 70 Secondary 60 50 40 30 Tertiary 20 10 0 pleens prees Kemp & Bryant, 2003 2nd experiment – on /z/ and /ks/ ending words The Kemp & Bryant result with adults was so surprising that we decided to extend the /z/ end sound data to onemorpheme vs two-morpheme verbs as well (praise, plays: sneeze, sees) and also nouns and verbs ending in /ks/ In this experiment, with 18-25 year old military recruits, we used pseudo-words, as well as a real word control, and we gave them a choice between two spellings The wily old fox focks That magician always was very cunning. tricks trix his audience. Jim sometimes We often gricks grix yox yocks after work. in the garden. The children saw two . klees kleeze proos at school . The children saw a at school . prooze Frequencies of correct choice for /z/ ending verbs in 205 young adults 35 30 Number of 25 participants out of 20 205 15 10 5 0 9 11 13 15 17 19 Number of correct choices out of 30 21 23 25 27 10% of sample significantly above chance 29 Frequencies of correct choice for /z/ ending nouns in 205 young adults 40 Number 35 of 30 participants out of 25 205 20 15 10 5 0 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 Number of correct choices out of 30 23 25 27 12% of sample significantly above chance 29 Frequencies of correct choice for /ks/ ending verbs in 205 young adults 40 Number 35 of 30 participants out of 25 205 20 15 10 5 0 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 Number of correct choices out of 30 15% of sample significantly above chance 29 Frequencies of correct choice for /ks/ ending nouns in 205 young adults 30 25 Number of 20 participants out of 15 205 10 5 0 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 Number of correct choices out of 30 17% of sample significantly above chance 29 Frequencies of correct choice for /z/ ending nouns in 72 young university students 25 20 15 10 5 0 14 16 18 20 22 24 Number of correct choices out of 30 26 28 87.5% of sample significantly above chance 30 Frequencies of correct choice for /z/ ending verbs in 72 young university students 25 20 15 10 5 0 14 16 18 20 22 24 Number of correct choices out of 30 26 28 83% of sample significantly above chance 30 Percent significantly above chance in choice of correct endings in the three samples N z nouns ks nouns 10-14 year olds 190 40 44 20 year recruits 205 12 17 20 year students 88 92 72 Conclusions from English and Greek studies The developmental process of children inferring rules on the basis of their word-specific knowledge seems to work better for Greek than for English children It also works much better for some English individuals than for others, probably for cultural reasons The reason for the striking individual differences in the English-speaking populations may be partly due to differences in exposure to text They are probably also due to the lack of explicit teaching about morphemic spelling rules You can teach morphemic rules to all children Three phases in the intervention programme There were phases in our studies of classroom intervention : Laboratory intervention studies with pairs of children conducted by our researchers Classroom intervention studies with classroom conducted by teacher, but closely scripted and supervised by ourselves Classroom intervention studies with our material (on a CD) and the programme decided by the teachers T. Nunes & P. Bryant (2006) Improving literacy through teaching morphemes Routledge Phase 1: A laboratory intervention with the ion/ian rule barbarian confession Christian conversation comedian combination magician discussion mathematician imagination musician invitation Nunes, Bryant, Pretzlik & Hurry Group pre-test Two intervention sessions: pairs Immediate post-test Two month interval Delayed post-test Four kinds of intervention We included four groups: Explicit (morpheme) N=40 C.A. 9y6m Implicit (morpheme) N=42 C.A. 9y7m Mixed (morpheme) (implicit followed by explicit) N=42 C.A. 9y7m Control (comprehension) N=76 C.A. 9y5m protect protection infect infection ? magic magician music musician ? The gang made a ____________________ to the police. confession The __________________________ was wonderful. musician Joe was a _______________ . Christian Mean adjusted correct spelling of ion/ian endings in real words (out of 16) 14 12 10 8 P re -te s t Im m e d ia te p o s t-te s t D e la y e d p o s t-te s t 6 4 2 0 E x p lic it m e th o d M ix e d Im p lic it m e th o d m e th o d C o n tro l Nunes, Bryant, Pretzlik & Hurry Mean correct endings (out of 8) with pseudowords ending in –ian & -ion 6 5 4 P r e -te s t Im m e d ia te p o s t-te s t D e la y e d p o s t-te s t 3 2 1 0 E x p lic it m e th o d M ix e d m e th o d Im p lic it m e th o d C o n tr o l Phase 2: A teacher intervention on –ion and –ian endings Number correct “-ion” and “–ian” spellings in pre- and posttests, when children were taught about “-ion” and “-ian” endings in classrooms by teachers 14 12 10 8 P r e -te s t Im m e d ia te p o s t-te s t D e la y e d p o s t-te s t 6 4 2 0 T aught group C o n tr o l g r o u p Nunes T. and Bryant P. (2006) Improving Literacy Through Teaching Morphemes. (Routledge) Phase 3: Intervention conducted by teachers in their own way: outcome measure vocabulary as well as spelling Group pre-test: spelling & vocabulary Approximately seven intervention sessions: classroom Immediate post-test : spelling & vocabulary 8-10 weeks interval Delayed post-test : spelling & vocabulary Pre- & post-test vocabulary measures logical illogical focal To solve maths problems you need to be very ___________________. painless painful pointless The doctor told Georgia not to worry because the injection would be _________________. disapprove disregard regard Because Tom had been lying the judge told the jury to __________________ his evidence. bluntness idleness alertness The teacher was very cross with John because he had been lazy. He said ‘ I am fed up with your _____’. Experimental Group N=319 Control Group N=182 Ages 7-12 years Intervention material er ist Example: making agents cleaner A person who cleans is a _______. er ist scientist A person who works in science is a ________. er ist robber A person who robs banks is a ________. ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Can you think of some more people words that end with: …er ? ? ? ? …ist ? ? ? ? ? ? er ist ian magician er ist ian library er ist ian librarian Morphemes change the meaning of words Count the morphemes and compare them with your neighbour’s un tied un dis im in un dis im in dishonest fortunate un fortun ate ness re ing ed er ian tion s un less ful The The boy boy was was ______with unhappy with hishis work work Because he had finished allallhis hiswork workhehewas wasfull fullof of________. happiness. 1 un happy happy happiness happy unhappiness Tom was full of _________ unhappiness because his mother had told him off. Tell me who the person is er or ian music… ian ive ist 1) reader 9) magician 2) director 10)dancer 3) cleaner 11)scientist 4) librarian 12)singer 5) fighter 13)musician 6) detective 14)write…. 7) artist 8) painter Identify the prefix and stems. What number is in the prefix? What does the made-up word mean? What is the most important difference between a bicycle and a tricycle? Bicycle What is it about the word that gives you a clue about this difference? Tricycle Binoculars Triangle What is it about the word that gives you a clue about the meaning? Experimental & Control Groups’ vocabulary test adjusted mean correct scores – out of 40 23 22 21 20 19 Experimental group Control Group 18 17 16 15 Pre-test Immediate post-test Delayed post-test Conclusions The ‘phonology plus word-specific knowledge’ approach is inadequate: children to some extent do learn spelling rules: and they NEED to Greek children learn about morphemic rules for themselves with the help of word-specific knowledge, but English children don’t do so well Some English children/adults acquire explicit and effective knowledge of morphemic spelling rules: others have a much weaker knowledge of these rules The reasons for these differences among English children are probably cultural These sharp individual differences would almost certainly disappear if children were taught about spelling rules systematically and entertainingly Final thoughts Orthographies are only partly systems for encoding the sounds of oral language They are also systems for representing deeper linguistic distinctions, like the “-ed” spelling for past tense inflections Our evidence suggests (1) that it is wrong and dangerous for psychologists and teachers to ignore these deeper regularities, and (2) that it is quite easy to encourage children to be interested in these regularities and to learn about them