Potatoes Complaint PDF

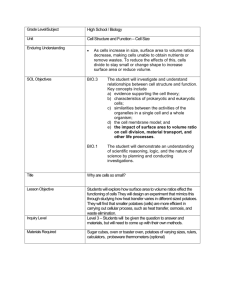

advertisement