31295013272603

A COMPARISON OF AUDIO-ONLY VERSUS

AUDIO-VISUAL SECOND LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION

IN FIRST-YEAR UNIVERSITY-LEVEL SPANISH by

TINA LYNN WARE, B.A., M.A.

A DISSERTATION

IN

SPANISH

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in

Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

Approved

Accepted

December, 1998

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Professors Rosslyn Smith, Roman Taraban, Susan Stein,

Harley Oberhelman, Robert Stewart and Janet Perez for their guidance and helpful criticism. In addition, I would like to thank the staff of the Texas Tech

Language Learning Laboratory, especially Phade Vader and Karissa

Greathouse, for their technical assistance and for allowing me to conduct my experiment in the Language Learning Laboratory. Gratitude is expressed to Kim

Rynearson for her assistance with statistical analysis. Also, I thank Keith Landry and McGraw-Hill Publishers, Inc., for donating texts.

Most importantly, my deepest appreciation goes to my parents, Richard and Signa Ware, and my sister, Teresa Estep. Without their support and encouragement, this project would not have been possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS li

LIST OF TABLES v

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION 1

II. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 6

A Comparison of Reading and Listening Comprehension 6

Listening Comprehension 9

Video and Listening Comprehension 12

The Other Receptive Skill: Reading 17

First Language Reading Versus Second Language Reading 18

Use of Video for Acquisition of Listening and Reading

Skills in the Target Language 20

History of the Language Lab 22

Video in the Language Learning Laboratory 24

Guiding Principles 28

Statement of Hypotheses 31 ill. METHOD 33

Participants 36

Student Eligibility Requirements and Selection for the

Experiment 38

Materials 41

Teaching Procedure 46

Testing Procedure 50

Experimental Design 53

IV. RESULTS 57

Skill Data 57

Results of Pre- and Post-Test Surveys 59

Opinions About General Usefulness of the Language Learning

Laboratory 60

Students' Preferred Language Learning Laboratory Activity 62

Participants' Opinions About Audio-Only Treatment 63

Opinions About Preferred Activity for Building Listening and

Reading Skills 63

V. DISCUSSION 66

Tests for Skill 66

Reading Comprehension 66

Listening Comprehension 67

Listening/Reading Comprehension 73

Student Opinions about the Language Learning Laboratory 76

Significant Results 76

Students' Opinions About General Usefulness of

Language Lab 11

Students' Favored Language Lab Activities 78

Lab Activity Preferences for Listening and Reading

Comprehension 80

Non-Significant Results 81

VI. CONCLUSION 82

LITERATURE CITED 90

APPENDICES

A. PRE-TEST SURVEY 96

B. PRE-TEST DEMOGRAPHIC QUESTIONNAIRE 97

C. MID-TERM EXAM 98

D. FINAL EXAM 101

E. POST-TEST SURVEY 104

F. POST-TEST DEMOGRAPHIC QUESTIONNAIRE 105

G. GLOSSARY 107

IV

LIST OF TABLES

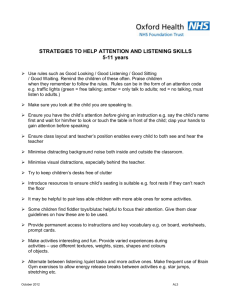

1. Demographic Information about Students 39

2. Previous Foreign Language Experience 40

3. Experimental Design 55

4. T-Tests for Skill 58

5. T-Tests for Likert Item Responses 61

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

During the second half of this century, the study of language acquisition has changed from its original emphasis on language teaching methodologies.

Since the late 1960s (Ellis, 1995), a number of studies have focused on second language learning, which "introduced a new research agenda and gave definition to the field that has come to be known as second language acquisition"

(Larsen-Freeman & Long, 1991, p. 5). This new research agenda looks closely at learner styles and the learning process. Researchers have learned much of what we know about language acquisition in the three decades since the introduction of the field of second language acquisition, or SLA (Dulay, Burt &

Krashen, 1982; Ellis, 1995). Gass (1989) uses Ellis' (1985) definition of second language acquisition, which is "the study of how learners learn an additional language after they have acquired the mother tongue" ( p. 499). The findings of second language research aid foreign language instructors in the classroom because teachers who use these ideas are better able to meet the needs of their students.

When referring to a language other than the first language, usually a distinction is made between a second language and a foreign language. A second language is a language being acquired in the milieu in which it is the native tongue, such as English being studied by a Korean in England. A foreign

language is a language acquired outside of an environment where it is the native tongue, such as a Spaniard's study of French in Spain. Although some researchers choose to differentiate between a second language and a foreign language, "SLA has really come to mean the acquisition of any language(s) other than one's native language" (Larsen-Freeman & Long, 1991, p. 7).

For the past three and a half decades, research in the areas of second language learning and acquisition has abounded. Researchers are constantly studying new methods of language learning, which refers "to conscious knowledge of a second language, knowing the rules, being aware of them, and being able to talk about them" (Krashen, 1982, p. 10), to find those which are most efficacious in the second language student's endeavor to acquire the target language. In addition, researchers study language acquisition, which Krashen

(1982) describes as the subconscious knowledge of the target language.

Investigators in SLA study people at all ages and levels of language proficiency, from babies to adults and from novice to native speakers. Studies cover topics such as the effects of explicit grammar instruction versus implicit grammar instruction in the classroom, music as a tool for teaching intonation, total language immersion, first language acquisition versus second language acquisition and the impact of social factors on language learning.

Ellis (1995) points out that the heightened emphasis on second language acquisition research that began developing in the late 1960s has been devoted to studying acquisition of the target language in the classroom. Earlier research

on second language acquisition concentrated on learners in natural settings.

Currently, many researchers analyze learning conditions and situations that resemble the classroom setting (Ellis, 1995). Even with the new concentration on classroom second language learning, one area of classroom second language instruction which has often been overlooked in studies of university language students is the language learning laboratory. Although not studied seriously, the language lab has outlived many tools for second language instruction. It has also been incorporated into most of the current methods of language acquisition that incorporate forms of the Direct Method (defined in the

Appendix) as a means of classroom instruction.

Many colleges and universities that offer foreign language courses require their students to attend instructor-taught courses coupled with time spent in the school's language learning laboratory to enhance language skills. Time spent in the language lab usually allows students to work independently and at their own pace while in the classroom they must follow the pace set by the instructor. Until the 1980s, most language laboratory activities were based on

ALM (audio-lingual method). These exercises consisted of listening to dialogues and stories in the target language on cassette tapes and completing workbook exercises that followed along with the tapes. Colleges and universities such as the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Texas at Arlington, Texas

A&M University in College Station and the Dallas County Community Colleges, as well as schools in the University of Illinois and University of Minnesota

systems, to name a few (Landry, 1997), have adopted new language learning laboratory materials to replace the audio cassette activities that accompany many foreign language textbooks such as Dos Mundos, the text used by Texas

Tech University (from 1994-present). These schools have begun to use an audio-visual language lab program, called Destines, which uses videocassette activities; this series closely resembles its predecessor, the French In Action

Series developed by Capretz (1988). Instead of listening to cassette tapes, students watch videos and follow along with workbook exercises. These videos follow a soap opera format, with thirty-minute episodes of a continuing story performed in formal and informal speech in the target language. During the videos, the story line stops frequently to allow for a summary of the action and introduction of new vocabulary presented in English. In addition, the differences between the various dialects and levels of language formality presented in the video are explained.

Both the French in Action Series and the Destines video programs were developed to improve listening comprehension skills among foreign language students of French and Spanish, respectively. Because both reading and watching videos are visual activities, current research (Secules, Herron &

Tomasello, 1992; Chung, 1994; Ciccone, 1995) favors video exercises over audio-lingual ones for building skills in reading comprehension as well.

My research question focuses on whether audio-only or audio-visual modes of language learning laboratory instruction more effectively aid university

students in building comprehension skills in reading, listening and the combination of listening and reading in the target language.

The Review of the Literature, Chapter II, is a review of the research about the skills of listening and reading individually, and in comparison with each other. This chapter also compares current research with previous findings about the use of video in the language lab. A brief history of the language learning laboratory appears as well.

Chapter III is a description of the methodology and an explanation of the components of the analysis, which include the materials used, demographic information about the participants, eligibility requirements, teaching and testing procedures and the experimental design of the study.

Chapter IV is a description of the results of the study, including the statistical analyses related to each of the three skills tested: listening, reading, and the combination of listening and reading. Participants' expressed preferences for language learning laboratory exercises, whether audio-only or audio-visual are also discussed.

Chapter V includes a discussion of the implications and possible explanations for the results of the investigation into using audio-only and audiovisual language learning laboratory activities to build skills in listening, reading and the combination of listening and reading. The conclusion. Chapter VI, summarizes the results of the experiment and suggests topics for future research.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

A Comparison of Reading and Listening Comprehension

When asked to name the elements of a language a linguist's typical response would be that four skills exist for each language: speaking, writing, listening and reading. Often, speaking and writing have been paired as the active skills and listening and reading as the "passive" skills (Oiler, 1973).

However, in the last two decades, listening and reading both have begun to receive recognition as receptive, active and conscious components of language

(Barnett, 1989; O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993; O'Malley, Chamot & Kupper, 1989) which require listeners and readers to actively "produce understanding" (Barnett,

1989, p. 2) of the oral and written messages they encounter. This research is diminishing the perception of listening and reading as passive skills.

On the surface, listening and reading seem like completely different mental processes. However, it is the experience of receiving written and oral language, not the comprehension process of oral and written messages, that presents disparities between listening and reading. Horowitz and Samuels

(1987) point out that listeners hear oral language, which is episodic, occurring in the present time, narrative and natural. In addition, these researchers point out that messages are implied with body language and intonation. Therefore,

"much can remain unsaid, ...oral language need not be explicit because these

nonverbal cues and the voice can convey considerable information which evokes the meanings that are normally carried by the written discourse" (p. 7).

Listeners and speakers generally share face-to-face interaction, while readers and the authors of a given text do not (Danks & End, 1987). Readers deal with written language which is" artificial...formal, academic, and planned; it hinges on the past and is reconstructed In such a way that in the future it can be processed by varied readerships" (Horowitz & Samuels, 1987, p.7). Written language is often affiliated with books and explanatory prose regularly found in academic settings (Horowitz & Samuels, 1987) and has been called "the most elaborate form of language" (Benson, 1995, p. 2). In a testing situation, readers have more control over written language than listeners have over oral language.

Readers can read a text several times while listeners do not have the opportunity to hear a passage as many times as they desire, nor can they stop during a listening exercise to explore a new word or phrase (Danks & End,

1987). Reading and listening vary where the linguistic stimulus is concerned.

Reading employs a visual stimulus while listening relies on an auditory one; both skills are independent of each other (Townsend, Carrithers & Bever, 1987).

With the differences in decoding oral and written language, it is possible to believe that reading and listening have nothing more in common than their classification as receptive language skills.

Nevertheless, convincing research exists which shows the similarities between listening and reading, especially where comprehension is concerned. In

addition to their common, but misleading, label as the "passive" skills (Barnett,

1989), listening and reading are language components which require comprehension rather than production. Both skills make use of cognitive structure during the comprehension process (Danks & End, 1987). Lund (1991) defines comprehension as the "construction of meaning using both the decoded language and the comprehender's prior knowledge" (p. 196). Readers and listeners both must decode the written and oral messages they encounter in order to understand them. Reading and listening share congruent processing strategies which include looking or listening for familiar words, attempting to grasp the general concept of the passage and expressing a sense of satisfaction with the ability to understand the message (Bacon & Finneman, 1990).

According to O'Maggio-Hadley (1993), listening and reading comprehension share the goal of not only deciphering the intended message but also knowing how to respond to it.

Both listeners and readers employ top-down and bottom-up processing in their decoding procedures. Morley (1990) describes top-down, or conceptuallydriven, processing as being "evoked from an internal source, from a bank of prior knowledge and global expectations about the language 'world'" (p. 331).

As listeners/readers are presented with a message, they use their general understanding of it and work towards a more specific knowledge of the message.

O'Maggio-Hadley (1993) describes a reader's top-down processing experience as one in which a reader begins with a global understanding of a topic and

8

works down to the precise elements of the passage, such as words and syntax.

Background information, or available knowledge, coupled with "insufficient linguistic skills may bias the reader towards top-down processing" (Kozminsky &

Graetz, 1986, p. 6).

Bottom-up, or data-driven, processing is the opposite of top-down processing (Kozminsky & Graetz, 1986). When readers and listeners employ bottom-up models of comprehension, they look at specific details, such as phrases, morphology and syntax, and move toward a general understanding of the text (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993). Theorists believe that readers and listeners use both bottom-up and top-down processing (Richards, 1990), and some argue that these processes take place simultaneously. "Details are attended to...while conceptual understanding of a more general nature allows the listener or reader to anticipate and predict" (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993, p. 136). Kozminsky and

Graetz's (1986) study found that second language learners with sufficient background knowledge employ top-down processing while students reading in their native language, with weak background knowledge, utilize bottom-up processing.

Listening Comprehension

Rubin (1990) states that "listening consists of processing information which the listener gets from visual and auditory clues in order to define what is going on and what the speaker is trying to express" (p. 309). Lundsteen (1979)

calls listening the "reception of any kind of sound" (p. 21). Researchers include the knowledge of specific linguistic structures, learning to use non-pedagogical contextual cues, understanding native accents, keeping up with native speaker speed and recognizing a wide range of lexical meanings in their definition of listening comprehension (Secules, Herron & Tomasello, 1992).

Listening also varies across different types of contexts. The circumstances in which oral language is used differentiate listening from other tasks associated with language (Byrnes, 1984). Byrnes (1984) recognizes the four modes of speech, classified by the situation listeners are in, as they are described by Belle (1980):

(l)spontaneous free speech, characterized by the interactiveness of the situation...(2) deliberate free speech as it occurs in interviews and discussions...(3) oral presentation of a written text as in newscasts, commentaries, and lectures where transmission of information is the objective...(4) oral presentation of a fixed, rehearsed script such as on stage or in a film. (p. 319)

Types of speech associated with interactional communication involve maintaining communication rather than delivering information and, therefore, the focus is on the phatic, rather than cognitive, plane. When listening for information is the purpose, listeners often receive information in "short bursts within a generally transactional framework" (p. 319), and recalling details is essential. Non-transactional speech usually lasts longer and contains fewer linguistic errors than interactional communicative situations. This type of

10

listening does not require listeners to recall details but rather to acquire a global understanding of what they hear (Byrnes, 1984). In spite of the fact that listening has traditionally been the "neglected" skill of language instruction, undeniably it is the single language skill used most in human communication. We can expect to spend twice as much time listening as speaking, quadruple the time in listening over reading, and five times more listening than writing. (Morley, 1990, pp. 317-318)

According to Long (1986) language production is not possible without first acquiring competence in listening. One can see the obvious need to focus more attention on the area of listening, especially where language learning is concerned, based on the amount of time we spend listening versus using other language skills. O'Maggio-Hadley (1993), Long (1986) and Meunier-Cinko

(1995) assert that developing listening skills builds confidence with the target language.

Listening remains something of a mystery to researchers. Researchers do not agree on what happens during the listening comprehension process

(Long, 1986). Unlike the "active" skills of writing and speaking, listening is not easy to observe, which is part of the reason that there was little published material that focused on teaching listening before the 1980s (O'Maggio-Hadley,

1993). Foreign language instructors used to teach their classes based on the assumption that students would acquire listening proficiency on their own.

However, in the last two decades researchers have recognized the need to

11

concentrate on listening and have emphasized it in the language classroom. In the 1990s, there has been growing interest in designing materials to teach [listening] comprehension more actively, especially through the use of culturally authentic texts, videotaped materials, and computer-assisted instruction that allows for greater interaction between the learner and the text,

(p. 165)

Video and Listening Comprehension

Interest has increased in the usefulness of audio-visual exercises in the language learning laboratory, especially regarding the development of listening comprehension. Teaching trends from the 1980s include a greater emphasis on contextual listening and the use of authentic oral texts used for listening tasks

(Morley, 1990). Garza (1990) defines authentic texts as "materials that are prepared by native speakers of a language for other native speakers, and expressly net for learners of that language" (pp. 288-289). He continues his definition with examples of authentic materials that include print, audio and video materials manufactured for "local consumption quality" (p. 289). O'Maggio-

Hadley (1993) continues to suggest the use of authentic materials for language instruction, though Ciccone (1995) mentions that some researchers find authentic materials too challenging for students at lower language proficiency levels.

According to Meunier-Cinko (1992), "video essentially addresses listening skills. But the visual input a video provides integrates the audio

12

material in a context that helps students guess what they miss in an oral text"

(p. 150). Thus, Meunier-Cinko points out that even if students do not pick up specific details from a video they enhance their general comprehension skills.

They learn how a culture utilizes a tongue in order to create and communicate meaning (Ciccone, 1995). Additionally, video provides more authentic language situations than cassette tapes (Garrett, 1991).

With the recent attention video has received as a language learning tool

(Chung, 1994; Ciccone, 1995; Secules, Herron & Tomasello, 1992), research has begun which compares the development of listening comprehension skills through the use of video activities versus other traditional forms of exercises.

Secules, Herron, and Tomasello (1992) performed a semester-long experiment to compare videotaped instructional materials with native speakers in everyday situations to customary teaching methods such as classroom exercises and drills. They performed the study with university students in their second semester of French, and the analysis looked at listening comprehension. The study included four classes, two of which served as the experimental groups.

These groups viewed videos, called French In Action, on a weekly basis during one of their four weekly class days. The other two classes received instruction in the Direct Method (defined in Appendix G). Students who study a foreign language with a direct method spend large quantities of class time listening to the target language. The subjects who watched French In Action videos spent

13

large amounts of time listening to the target language, as well, though they were listening to and watching videos rather than a classroom instructor.

Participants in the experimental classes used the workbook, textbook and audio cassette tapes designed for use with the videos. The French In Action videos were designed to improve listening comprehension skills because they allow students more experience with native speech (at normal speeds) than traditional methods (Meunier-Cinko, 1992). Participants in the control group did not watch the French In Action videos, and they used a different textbook than the experimental groups.

In order to test the students' listening skills, at the end of the semester all four classes of students watched a video in French, then answered questions in

English about the video. Test questions employed English instead of French in order to test solely the pupils' skills in listening comprehension and avoid testing another factor, such as writing skills, in the target language (Meunier-Cinko,

1995).

The investigation revealed that students who used the French in Action video tapes had significantly higher test scores in the area of listening comprehension and with questions that involved main ideas, details and inferences than those who did not use the videos. In addition, the students who learned with the videos performed better on grammatical structures than those who used drills, and the video learning students reported that they enjoyed watching the videos (Secules, Herron & Tomasello, 1992, pp.486-487).

14

Concerning this same study, Ciccone (1995) points out that video materials improve student motivation and add realism to the classroom by providing

"important nonverbal Information that increases cultural understanding" while augmenting skills in the area of listening comprehension (p.206). Currently the only research that exists In regard to the French In Action study praises the investigation and the use of audio-visual exercises.

Chung (1994) studied whether the use of audio-only dialogues, or dialogues combined with single picture images, multiple picture images or moving-video images assisted college students in building listening skills in intermediate and advanced French classes. In addition, he compared these students with other students who only saw the visual segments of the same dialogues. Each of the 75 paid participants in the advanced (students with more than four semesters of French), intermediate (students in their third and fourth semesters of French) and visual images-only groups (participants of either advanced or intermediate French who only watched the dialogues) took a listening comprehension test, either prior to or after being exposed to four dialogues. The dialogues were audio-visual recordings of native Frenchspeakers who discussed purchasing clothes, purchasing wine, moving furniture and the use of computers. Two sets of the four dialogues were made. One set of tapes had audio and video and the other had only visual images of the 3-4 minute two-person dialogues. Each set included four tapes, all with one of four different dialogue orders: ABCD, BCDA, CDAB, DABC. Some participants

15

watched and listened to the dialogues while others only watched the dialogues.

As the participants were presented with the dialogues they received increasing amounts of information: starting with audio-only dialogues (except for the visual images-only group), then visual Images that began with a still picture, multiple pictures (which were like a slide show) and finally videotaped pictures.

Afterwards, participants were tested for their ability to recall main ideas and details and for their global knowledge of the dialogues.

Chung's investigation found that "images alone are not sufficient for representing a dialogue, unless generating inferences is the desired outcome"

(1994, p. 107). However, audio, combined with visual images, whether "one or more supporting images" (p. 92), improved listening comprehension with the

"combination of moving images with corresponding audio being the most effective" (p. 92). Students who could only remember a few details when they experienced the audio-only condition could "recall main ideas supported with details when provided with images" (p. 101). Moving images aided students in listening because of the paralinguistic cues provided. Some images helped participants to make predictions about the scene's content. These images most likely served as "advance organizers," or tools that allow students to recall their already existing background knowledge about a particular subject in order to make educated guesses about a situation. Advance organizers aid students in learning and remembering new material (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993).

16

Chung's study also concluded that higher-proficiency students are more skilled than lower-proficiency students in using the information available to them to interpret messages. Both levels of foreign language students shared an equal level of recall of visual images (Chung, 1994).

The Other Receptive Skill: Reading

With the exception of the era when ALM monopolized language teaching strategies, reading has played a weighty role in foreign language classroom curricula (Barnett, 1989). Savignon (1983) asserted that, until the 1980s, reading was almost the only goal of foreign language teaching. Barnett (1989) considers reading a primary means for academic language learning and points out three major reasons for reading instruction in the foreign language classroom: (1) reading is necessary for teaching literature; (2) competency in reading can be maintained after formal study in the target language is completed; (3) reading cultivates the maturation and improvement of literacy skills.

Reading has taken on a new image. Although in the past researchers considered capacities in the areas of listening and reading "passive" (Barnett,

1989), since the 1980s, researchers have called reading an active exercise. In addition, reading is a skill that belongs in the communicative classroom,

"especially when authentic materials can serve the dual purpose of developing reading skills and fostering cultural insights and understanding" (O'Maggio-

17

Hadley, 1993, p. 163). Danks and Pezdek (1979) define learning to read as the transfer of auditory signals of language, which one has already learned, to new visual signs for the same signals. Barnett (1989) calls reading "communication,

...a mental process, the reader's active participation in the creation of meaning, a manipulation of strategies...essential to appreciating target language literature"

(p. 2).

First Language Reading Versus Second Language Reading

Existing theories for teaching reading comprehension vary. Some researchers encourage reader schema and background theory. Schema theory states that learners comprehend current experiences based on both previous experiences and world knowledge (Barnett, 1989; Long, 1989). Goodman

(1972) interprets reading as a psycholinguistic process, one that relates to the study of the connection between language and the behavioral qualities of language users. Barnett (1989) emphasizes the issue of differences in first and foreign language reading, asserting that second language readers are handicapped in comparison to first language readers. Reading in the target language strains short-term memory more than reading in the first language due to the presentation of a foreign linguistic code (Barnett, 1989). In addition, second language readers face cultural barriers in authentic reading texts because the texts are woven with the culture in which they were written. In order to comprehend texts, some readers in the target language implement

18

comprehension strategies that they engage in their first language reading

(Barnett, 1989). These strategies differ from learner to learner based on various factors which range from reader purpose and enthusiasm to proficiency in the target language and schemata (Barnett, 1989).

Researchers point to the learners' proficiency in the target language as a determining factor for whether learners transfer their first language reading strategies, or "problem-solving techniques readers employ to get meaning from a text" (Barnett, 1989, p. 36), when faced with a passage in the target language.

Beginning second language learners' target language reading strategies deviate from their reading abilities in the first language. Experiments with lower-level readers in a second language demonstrate that they tend to focus on the individual words of a text and comprehend less than one-third of the passage. In addition, these readers tend to use bottom-up strategies for comprehension.

Novice and intermediate learners attempt, sometimes successfully, to employ first language reading strategies when reading in their second language, though this practice is more common among advanced readers (Barnett, 1989).

Advanced foreign language readers also use top-down processing strategies

(Oiler, 1973; Kozminsky & Graetz, 1986) and are better equipped to apply schemata to a reading passage (Kozminsky & Graetz, 1986).

No conclusive evidence exists either for or against the idea that first language reading strategies transfer to second language reading.

Comprehending written messages "depends in great measure on what readers

19

already know about a topic and on what they expect in terms of text structure.

General language proficiency affects how much readers understand" (Barnett,

1989, p. 63).

Use of Video for Acguisition of Listening and Reading Skills in the Target Language

Lund (1991) sees a parallel between the processes of reading and listening which supports the use of video for building skills in these language components. "By providing analogous cues, video encourages the development of useful reading techniques" (p. 209). Video images serve as the equivalent of written cognates with images that often translate notions of chronology, comparison, or contrast not unlike adverbial and conjunctive expressions; and change in voice or actor can provide the aural or visual equivalent of proper names, pronouns, quotation marks and other identifying graphic features, (p. 209)

Ciccone (1995) concluded in his article "Teaching with Authentic Video: Theory and Practice" that video raises the comprehensibility of reading material on similar concepts. He states that the mixture of authentic video materials with authentic reading materials will improve both listening and reading comprehension because "working with authentic video materials as meaningful, interesting language to be decoded encourages the fundamental processes needed to improve reading comprehension and increase reader satisfaction" (p.

209).

20

Kasper and Morris (1988) examined differences in perceived difficulty among types of presentation media (in the native language) that included electronic mall, audio-only and audio-visual media. Their investigation included

24 volunteers, both business administration faculty and graduate students, who participated in the blocked design experiment, indicating that all subjects received the four treatments. Subjects were presented with four types of media: paper, electronic mail, audiotape and videotape, one at a time. After receiving a message in each medium, which they could refer to only one time, subjects took a quiz on paper to measure their comprehension of the message. Kasper and

Morris concluded that no there is no difference in message comprehension between audio-only and audio-visual media, nor between electronic mail and paper media presentation in the first language. These results raise the question of whether there would be no difference in comprehension of audio-only versus audio-visual media presentation in the second language as well.

The use of video has been encouraged as a supplement to traditional classroom teaching, rather than as a replacement, since the experimental television lessons of the 1960s proved unappealing to teachers and students

(Hocking, 1964). Video has, however, been suggested as a replacement for audio cassette tape language learning laboratory exercises because of its ability to aid students in individual learning in a more appealing, modern, possibly more effective way than audio cassettes.

21

Historv of the Language Lab

The year 1904 marks the beginning of the language learning laboratory in

England, though the term "language lab" was not coined until the 1940s. The language learning laboratory has been defined as "a special room with electronic equipment set aside for language practice by students. The tape recorder alone...does not constitute a laboratory" (Huebner, 1967, p. 109). In the lab, students have the opportunity to practice the target language at their own pace, as frequently as they choose. During the 1940s, the first language labs were built for colleges (Hocking, 1964). The National Defense Education Act

(NDEA) of 1958 provided grants to U.S. schools that allowed for the installation of language labs on school campuses (Green, 1975; Huebner, 1967). Schools opened up language labs in an effort to economize on the teacher's time (Green,

1975), supplement class practice time, create "simultaneous yet individualized student practice" (Hocking, 1964, p. 35) and to "provide a convenient means of hearing and responding to audio lingual drills" (Stack, 1971, p. 3).

Although many colleges, universities, and even some high schools boast that they have elaborately equipped language learning laboratories, preliminary studies of the lab found discouraging results about its usefulness. The Keating report of 1963 found it "of doubtful value...one week in the lab produces poorer results than no lab at all" (Green, 1975, p. 14). Difficulties existed in measuring the usefulness of the language lab. There was a problem with "isolating the variable that it was proposed to measure and of holding constant all the other

22

variables affecting learning in a normal classroom teaching situation" (Green,

1975, p. 34). Keeping the "control" and the "experimental" groups of students intact for enough time to make significant comparisons of their progress was an additional problem (Green, 1975).

Originally schools used the language learning laboratory to provide auditory activities for their students. As stated previously, colleges began to open language labs in the 1940s (Hocking, 1964) just a decade before the audio-lingual method (ALM) would become the most common form of foreign language learning outside of the classroom (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993). The

United States armed forces used ALM almost exclusively to train its soldiers in language to send them overseas and to fight in World War II. Funding from the

NDEA in the 50s and 60s also provided for the training of foreign language teachers with ALM. These ALM exercises, also called Aural-Oral, usually consisted of dialogue memorization and listening drills, and they de-emphasized teaching grammar in the classroom (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993).

As late as the 1970s the tape and recorder were the staple items of the labs, which provided a "drill ground guided by authentic native voices...giving intense active practice in application of structural and phonetic principles previously presented in the classroom" (Stack, 1971, p. 118). Also, learners had the opportunity to practice the different aspects of the target language individually at their own pace, and as frequently as they chose (Huebner, 1967).

With the cassette tape and recorder, language pupils participated in a variety of

23

listening and "audio-active" response activities. These exercises consisted of student oral response (usually in a microphone or cassette recorder) to a dialogue or question heard on the cassette tape. Other activities included

"audio-active-compare," or "listen-record-respond," exercises in which the learner listened to a broadcast, responded to it, and listened to a recording of his or her response in order to compare it with the broadcast and chart his or her progress in the language (Stack, 1971). ALM activities fit the idea that "the steps in language teaching are (1) hearing (2) speaking (3) reading (4) writing"

(p. 117), in that order, with hearing and speaking classified as "audiolingual skills" and reading and writing referred to as "graphic skills" (p. 117).

Video in the Language Learning Laboratorv

As modern technology has continued to change so have language laboratory materials. Filmstrips, projectors and videocassettes brought audiovisual learning experiences with them, which have proven both entertaining and educational for students. However, before discussing the benefits of audiovisual language learning tools, I will review the research from the past that favored audio-only exercises for language teaching. This research from before the establishment of the video era will explain why audio-visual learning was not embraced with the same enthusiasm with which videos were welcomed outside of the language learning laboratory.

24

Results of investigations conducted before the 1980s were unfavorable regarding the use of audio-visual language lab activities. Analyses from the

1960s and 1970s described the use of video as helpful only for teaching culture and promoted audio-aural activities as the stronger means for developing skills in the target language. "By and large, the audial [sic] aids seem to be reserved for the linguistic aspect and the visual aids for the cultural" (Huebner, 1967, p.

63). Audio-visual aids were seen as unsuitable for the "bulk of linguistic training" with their strength lying in "their ability to give the student a simulated experience in the foreign country" (Huebner, 1967, p. 63), mainly to teach culture (Hocking, 1964). Cassette tapes were also considered better than videos at guiding students' reading while allowing them to hear correct pronunciation and phonetic principles (Stack, 1971) and preventing them from getting off task, all which aid in comprehension (Huebner, 1967). The tape recorder was advocated for supporting "oral memory" and presenting students with accurate sentence rhythm and intonation (Huebner, 1967). However,

Huebner (1967) admits that listening to the tapes can become tedious.

Filmstrips were suitable for creating interest in the country where the target language was spoken but not for teaching the formal aspects of the target language, such as grammar. In addition, foreign language teachers in the 1960s said they were intimidated by "new technology," such as filmstrips and projectors. They added that they did not find audio-visual aids useful or cost effective (Huebner, 1967).

25

More problems occurred with the language lab when television instruction was introduced. In addition to feeling intimidated by "new technology," foreign language instructors hesitated about using television in the classroom because of the television programs themselves. Language lesson productions for television usually were thrown together quickly, lacking planning and organization. Viewers of these programs, which gave a "cheap and false impression" (Stack, 1971, p. 53) of foreign language learning, eventually lost interest in them. In addition, a research project utilizing television to teach

French found that "t.v. lessons alone, without class follow-up, are ineffective.

For satisfactory achievement, at least thirty minutes of follow-up time a week are needed at the first two levels and at least 45 minutes at the third level" (Hocking,

1964, p. 71). In the early 1960s educators feared that classroom instructors would be replaced by "canned" television lessons, lessons conducted by teachers via television rather than live classroom sessions. Later, however, it was concluded that the impersonality of these "canned" lessons that did not appeal to teachers did not appeal to students either (Hocking, 1964). In spite of its troublesome introduction into foreign language instruction, the use of video as a teaching tool in the classroom and the language learning laboratory has endured.

Many researchers and teachers now praise the use of videos and television for language instruction and include audio-visual materials in their foreign language curricula. According to Secules, Herron and Tomasello (1992),

26

"video permits learners to witness the dynamics of interaction as they observe native speakers in authentic settings speaking and using different accents, registers and paralinguistic cues (e.g., posture, gestures)" (p. 480). Video teaches the social dimension of language including the previously mentioned register or level of formality: formal talk versus slang (Rice, 1983). According to

Meunier-Cinko (1992) television and videos are effective in motivating students, adding realism and providing students with "important non-verbal information

(such as greeting patterns, distance between interlocutors and the like)...With video, language takes on another dimension" (pp. 149-150) and encourages global understanding strategies (Ciccone, 1995). Although the same language may be spoken in a variety of countries, the same word may have a different meaning in different countries. For instance, a coche in Mexico is a car while in

Costa Rica a coche is a baby stroller. The use of video helps students with semantics by demonstrating "that the meaning of specific words or utterances varies according to the speaker's identity and situation, hence the importance of recognizing systems of discourse employed by a particular passage" (Altman,

1989, p. 4). Videos allow learners to begin to picture "real-life target-culture examples" of items they have studied allowing them to develop an "authentic visual dictionary" (p. 16).

Video also offers constant contextual updating, which provides maximum comprehension of the language and offers the potential to teach linguistic and contextualizing skills needed for understanding future passages in the target

27

language, whether or not they are presented in the video (Altman, 1989).

According to Ciccone (1995):

Authentic video makes linguistic input more comprehensible by embedding It in a context of extralinguistic cultural cues that assure the transmission of meaning when the complete grammatical and lexical decoding is not likely to be achieved...(students) have greater difficulty in understanding audio-only conversations than video materials despite similarities in topic and preparatory materials, (pp. 205-206)

In addition, Garza (1990) adds that video material "is more easily contextualized, and, thus, more accessible to the learner" (p. 292). He also states that video allows instructors to provide more authentic language situations than without it.

Thus, the richer context provided by audio-visual messages over audio-only ones makes audio-visual messages easier to decipher.

With advances and improvements in both equipment and learning materials, the language learning laboratory has come to be seen as a useful tool in language learning. Hocking's (1964) prediction that "while the language laboratory is not the only point of contact between technological development and language teaching, it has been and will remain the most important one for some time to come" (p. 61) appears to be true, even three decades later.

Guiding Principles

Researchers like Ciccone (1995) contend that audio-visual messages are easier to decode than audio-only messages by reason of the extralinguistic cultural cues that the former provide, as explained earlier. Research in the field

28

of psychology alludes to the same Idea. Braine (1988) says that in the last 25 years, first language acquisition has received great interest from psychology researchers. From first language acquisition research done by psychologists with children, one may infer that audio-visual activities will more effectively aid second language students in building language skills in the areas of reading and listening comprehension. Both Pinker (1987) and Braine (1988) state, through their individual first language acquisition models, that children use meaningful context to extract grammatical categories and information. This meaningful information is used to code utterances and language.

In his article "The Bootstrapping Problem in Language Acquisition,"

Pinker (1987) explains that when acquiring the first language, children use the context of the situation they are in when they hear language spoken to help them to make sense of the utterance they have heard. Thus, the situational context serves as a bootstrap to the utterance or language that is heard in order to comprehend it. Children employ meaningful context to make sense of grammatical rules. I postulated that adults learning their second language would also bootstrap situational context to audio-visual messages in the second language in order to understand the meanings of these messages. The

Bootstrapping Hypothesis also rejects the use of error correction as a means for first language learning. MacWhinney (1987) praises Pinker's model for the

"evidence indicating that children do not learn by correction or 'negative instances'" (p.xii), which is in agreement with the Natural Approach.

29

Braine (1988) discusses the "sieve memory" for first language acquisition in his article "Modeling the Acquisition of Linguistic Structure." According to

Braine's conceptual, linguistic long-term model, children add to previously learned information as it Is acquired in an effort to learn language. Children learn general patterns of language first, and gradually their language becomes more sophisticated. They begin to use specific language patterns that are exceptions to the general patterns, and they learn when these specific patterns take precedence over the general ones. For instance, children will learn that the past tense in English is generally formed by adding the suffix -ed to a present tense verb, and they will add -ed to every verb when they want to speak in the past tense. Eventually, children will learn that in some cases, such as with the verbs "go," "throw," and "swim," adding the -ed suffix is incorrect. They will begin to learn the specific patterns of irregular verbs and replace "goed,"

"throwed," and "swimmed" with "went," "threw," and "swam," respectively.

Braine (1988) uses the term "sieve" in his "sieve memory" model because he postulates that although children will hear errors in language, the recurrence of these errors is rare. Therefore, the errors will be erased from the child's memory, allowing for the acquisition of the correct language they hear. Like

Pinker, Braine believes that error correction is unnecessary.

If second language learners follow the same pattern when they are learning their second language that they did when they learned their first language, one may hypothesize that audio-visual learning activities provide a

30

richer context for encoding oral and written information in the target language than audio-only learning exercises. Applying both Braine's (1988) and Pinker's

(1987) models to adults' listening and reading comprehension suggests that audio-visual language laboratory exercises will be more effective than audioonly techniques because audio-visual activities provide a richer and more abundant context for students to use in decoding oral and written messages.

Statement of Hvpotheses

As stated previously, my interest lies in the gap in empirical research concerning language learning laboratory exercises and teaching materials developed to improve listening and reading comprehension skills in the foreign language. Influenced by my previous experience of teaching a second language through the use of both audio-only and audio-visual language lab exercises, I conducted a one-semester study of the progress of first-year Spanish students' receptive second language skills with the use of audio-only and audio-visual language lab materials. My hypotheses are:

Hoi: There is no difference in listening comprehension performance in the second language of students who receive systematic audio-visual instruction or audio-only instruction in the language learning laboratory.

Ho2: There is no difference in reading comprehension performance in the second language of students who receive systematic audio-visual instruction or audio-only instruction in the language learning laboratory.

31

Ho3: There is no difference in the combined listening/reading performance in the second language of students who receive systematic audio-visual instruction or audio-only instruction in the language learning laboratory.

32

CHAPTER

METHOD

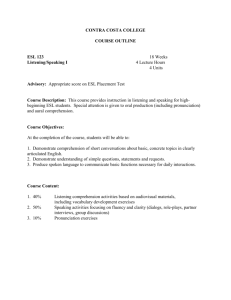

Spanish 1501 was chosen for the experiment in order to work with students with the least possible amount of experience in the language. Spanish

1501 students have no more than one year of high school language study; students with two years or more high school instruction must take the dual first and second semester class, Spanish 1507. The 1501 pupils all received instruction in the current method of Spanish instruction at Texas Tech University,

Terrell's Natural Method. This communicative mode of instruction, which evolved from the Direct Method, emphasizes total immersion into the target language with little or no use of the students' native language in the classroom

(Terrell etal., 1994).

Total Physical Response, or TPR, is a component of the Natural Method, formulated by Asher. The Natural Method "is based on the belief that listening comprehension should be developed fully, as it is with children learning their native language, before any active oral participation from students is expected"

(O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993, p. 105). Also, "skills can be more rapidly assimilated if the teacher appeals to the students' kinesthetic-sensory system" (p. 105).

Therefore, Total Physical Response, or TPR, is an integral part of the Natural

Method. In TPR body movements are considered part of the learning process.

Often the teachers present the target language to students in the form of

33

commands. Students respond to the commands in order to demonstrate their comprehension.

The Natural Method emphasizes communicative competence in the target language and encourages only minimal grammar training in class. However, students must have some knowledge of syntax, such as gender, tense, number marking and subject-verb agreement, in order to fully comprehend the oral and written messages they receive In Spanish. For instance, subject pronouns are often omitted in spoken and written Spanish, especially when speaking or writing in both the singular and plural forms of the first person, because the subject Is evident from the verb ending. Students need to understand this concept in order to know who the subject is in a particular passage. Therefore, textbooks for the

Spanish 1501 course include detailed, structured grammar explanations and exercises that students complete outside of class. Principles of the Natural

Method suggest that instructors collect students' grammar assignments and give them "systematic feedback" on the homework though the responsibility of improving syntactical skills lies on the student. The Natural Method assumes that students need a knowledge, though only a minimal one, of grammar in the target language to be able to communicate and that these students will be motivated to complete grammar assignments outside of class (O'Maggio-Hadley,

1993).

Instructors devote class time to developing communication skills in the target language. Teachers promote speech production in the second language,

34

but they do not require students to speak until they are ready, in accordance with the theory behind the Affective Filter Hypothesis (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993) which also informs the Natural Method. The Affective Filter Hypothesis states that attitudes and feelings do not impact language learning directly but can prevent students from acquiring language from input. If a student is anxious or does not perceive the target culture in a positive light, he or she may understand the input but a psychological block (the Affective

Filter) will prevent acquisition. (Terrell et al., 1994, p. xvii)

Teachers, therefore, are encouraged to foster a "non-threatening and friendly atmosphere in the classroom" (Baltra, 1992, p. 45). Terrell's Dos Mundos

(1994), designed for instruction in the Natural Method, served as the text for all first year Spanish classes at Texas Tech.

The study conducted at Texas Tech is similar to, and possibly an improved version of, the Secules, Herron and Tomasello (1992) experiment. All participants in the Texas Tech study used the same textbooks and were compared against themselves. The French In Action study, on the other hand, had two sets of subjects (experimental and control subjects), and each set of subjects used different textbooks, creating more uncontrolled variables for

Secules, Herron and Tomasello. Some of the uncontrolled variables include age, motivation, attitude, level of frustration and amount of previous experience in foreign language study. The aforementioned uncontrolled variables were not present in the study conducted for the Destines experiment because the

35

participants in the study served as their own controls and were not compared against other students.

Participants

Fifty-six Texas Tech University students (31 male and 25 female) in their first semester of Spanish served as participants for this study. These participants came from the seven sections of the Spanish 1501 classes taught during the fall 1997 semester at Texas Tech. Participants ranged in age from 18 to over 36 years and were divided naturally into either a morning or an afternoon group as demonstrated in Table 1, depending on when their discussion section met. The morning group was composed of 15 males and 18 females; seven were sophomores, 13 juniors and 13 seniors. Twenty-three students were in the afternoon group, which included two sophomores, 12 juniors and nine seniors.

Caucasian students composed 83.9% of the sample, and Hispanic students made up 10.7%. Of the participants, 3.6% were African-American and

1.8% were Asian. I looked at the participants' ethnic backgrounds in order to learn whether a significant number of students came from Spanish-speaking backgrounds. Participants who grew up speaking Spanish or hearing it spoken in the home would have had an advantage over the other students in the study.

These participants from Spanish-speaking backgrounds would have had a familiarity with listening to, and possibly reading, Spanish that the other participants most likely would not have had. Therefore, the Hispanic students

36

could possibly have had higher listening and reading scores than the other students based not on the treatments they received in the study, but from skills the participants developed in their homes. However, the percentage of Hispanic students was not large enough to skew the results.

The majority of the students in this study, 44.6%, were juniors; 37.5% were seniors, 16.1% were in their sophomore year, and one student who was auditing the course did not have a classification. Few freshmen have the opportunity to take first-year Spanish because the class sizes are limited, and upperclassmen are given preference where course availability is concerned.

Of the 56 participants, over half (57.1%, or 32 students) had studied one or more of six different foreign languages prior to taking Spanish 1501. Latin was the most common previously studied language. Spanish was second to

Latin as 10 and nine students, respectively, noted experience in these languages. Of the rest of the participants with previous foreign language experience, eight had studied French, two had studied German and one student spoke Chinese. Some students had received instruction in two languages other than English. Of the students, one had been introduced to German and

Spanish, one to French and Spanish, and two had some familiarity with French and Russian.

Almost half, 44.6% of all participants, experienced previous foreign language instruction in high school. One student had second language

37

instruction in junior high school, four in college, and two indicated that they were introduced to a foreign language in a medium other than school.

Only seven participants, 12.5%, had used a language learning laboratory before participating in this experiment Four of these students' lab activities consisted of listening to cassette tapes and completing workbook exercises. Of the other three with lab experience, one had used video and audiotapes with workbook exercises, one had used cassette tapes only, and one indicated executing "other" types of language laboratory activities. For the other 87.5% of the participants, 49 students, their participation in the experiment constituted their first exposure to the language learning laboratory. Therefore, these participants probably had few, if any, preconceived positive or negative ideas about the language lab based on personal experience. This lack of experience in the lab on the part of almost 90% of the participants allowed students to give unbiased opinions about it on the Pre-Test questionnaire.

Student Eligibilitv Reguirements and Selection for the Experiment

Students participated in the experiment as a part of their normal class activities. All pupils in Spanish 1501 had the same language learning laboratory requirements. During the first week of classes, I met with all sections of the first semester Spanish classes. I explained to them that their Spanish class would participate in an experiment being conducted to gather data for a dissertation.

38

Table 1

Demographic Information about Participants

Group

Morning Afternoon

Number of Males 15 16

Number of Females 18 7

* Classification:

Sophomores

Juniors

Seniors

7

13

13

2

12

9

Note. Data are for the 56 students who completed the experiment.

" One student was auditing the course and did not have a classification.

39

Table 2

Previous Foreign Language Experience

Students with no previous foreign language experience

Students with previous foreign language experience

Previous languages studied

% of students

42.9

57.1

Latin

Spanish

French

German

Chinese

German and Spanish

French and Spanish

French and Russian

17.9

16.1

14.3

3.6

1.8

1.8

1.8

3.6

Note. Data are for the 56 students who completed the experiment requirements.

40

This explanation included a brief description of what their lab requirements and activities would be.

In order for their data to be eligible for the experiment, students had to fill out the pre-test survey and demographic questionnaire. In addition, they had to be present for the mid-term and the final exam and complete the post-test and demographic survey. Data were collected from all members of Spanish 1501 courses. However, data from those who did not meet the eligibility requirements were discarded without their knowing about it.

Materials

Pre- and post-test surveys, questionnaires, a mid-term examination, a final examination, and videos and workbooks from the Destines learning series constituted the materials used for the experiment. Destines (VanPatten, Marks,

& Teschner, 1992) is a video telenevela, a soap opera, series developed for use in the Spanish classroom, lab or in lieu of the classroom. The Destines videos present a combination of narration and dialogue. Each half-hour episode has a continuing story line, narrated in English, which pauses at various intervals to highlight grammatical concepts and vocabulary (in English). OthenA/ise the story and dialogue are presented completely in Spanish. The combination of English narration and the characters' dialogues are descriptive enough that listeners are able to understand the story line without visual aids. The McGraw-Hill

Publishers donated workbooks, called Viewer's Guides, that accompany the

41

Destines video series; they granted enough books for all pupils to have their own book. The Viewer's Guides have two sets of activities that accompany each episode in the series. The first set of exercises, called Preparacidn, asks participants to make predictions about what they imagine will happen in the upcoming episode, usually In the form of multiple choice questions. Such questions serve as "advance organizers" (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1983). Thus, these questions trigger the students' previous experiences watching episodes of the soap opera and completing the Preparacidn exercises. The triggering of students' previous experiences with the videos allows the new information and lessons in the current day's episode to affix themselves to the students' cognitive structures, or codes of already existing knowledge. Use of advance organizers assists students in learning and retaining new lessons (O'Maggio-Hadley, 1993).

The iJienes buena memoria? {Do You Have a Good Memory?) activities, the second type of exercises that accompanies each installment of the videos, include questions about what happened in the episode just viewed; these questions are usually multiple choice, matching or sequencing.

The pre- and post-test questionnaires asked each participant for demographic information, such as age category of learner and previous experience in studying a second language. Some students indicated on the pretest that they had had less previous language experience prior to taking Spanish

1501 than they indicated on the post-test. Soliciting the same information on both the pre- and post-test demographic questionnaire was done in order to

42

control for the students who were untruthful about their previous language experience. Of the three students who gave different information on the preand post- demographic surveys, all three of them said on the pre-test that they had less than one year of high school instruction in Spanish in order to be able to qualify to take Spanish 1501. On the post-tests, the students admitted to having one year of high school Spanish instruction. Students who have more than one year of high school instruction in Spanish are required to take the dual, first and second semesters combined, course if they want to receive credit for taking an introductory Spanish course.

The pre-test survey (included in the Appendix with the demographic information questionnaire) focuses on student opinions and preconceived notions about the language learning laboratory. It is composed of 11 statements about the language lab, each with a five-point Likert Scale. A number value of

1-5 was assigned for the possible ratings listed for each statement. The rating scale follows: 1= Strongly Disagree; 2=Disagree; 3=Neither agree nor disagree;

4=Agree; 5=Strongly Agree. Participants rated statements about how useful they thought the language learning laboratory would be for their acquisition of

Spanish. The post-test survey closely resembled the pre-test survey except that it asked students to rate statements about how useful they found the language learning laboratory after their one-semester experience.

The three-page, 30-question mid-term was composed using materials from the Destines tape script and audio script materials as well as questions that

43

I wrote. The combination listening/reading comprehension part of the exam came from the lab workbook exercises published in the Destines Study Guide, which the students did not have access to. This section made up one third of the test. The two passages used for the reading section of the mid-term came directly from the students' workbooks; I wrote the questions about the passages to ensure that the students had no previous access to them. Listening passages about familiar characters were chosen based on the premise that at the lowest proficiency levels, listening materials that present very familiar and/or predictable material content ...will be best, given that students will use their linguistic knowledge of the world to aid them in comprehension when their linguistic skills are deficient. (O'Maggio-

Hadley, 1993, p. 170)

Each reading exercise focused on a character that the students had some familiarity with from the Destines series In order to create a top-down processing reading exercise, as described in Chapter II. Goodman (1972) recommends the use of top-down processing exercises to help readers make predictions about the text they are working with and to help them "confirm or reject their hypotheses as they process the information in the text" (p. 133). The information about these characters had not been presented in the story line of the episodes, and students had not been required to read the passages prior to the test.

The final exam closely resembled the mid-term in its format. The exam was made up of 30 questions: 10 listening comprehension, 10 reading comprehension and 10 listening/reading comprehension. The 10 listening comprehension questions were a combination of questions that the Destines

44

series included in the Study Guide and questions that I wrote. The two passages that made up the reading comprehension texts came from the

Destines Study Guide. These reading exercises, like the ones from the midterm, focused on a character from the Destines series. Unlike the mid-term, however, students did not have prior access to the texts that appeared on the final. I wrote the multiple-choice questions that accompanied each passage.

In order to complete the mid-term and the final exam, participants needed a general knowledge of syntax. They had to understand subject-verb agreement, adjective agreement and telling time. In addition, they needed to recognize cognates from English. For the listening/reading portion of the midterm students should have understood present tense reflexive verbs, and, for the reading section of the final exam, the difference between present and past tense verbs.

Because students viewed or listened to the Destines stories in the language lab, and were, therefore, familiar with the language lab setting, I used the lab's video and audio equipment to give the mid-term and final exams.

Students sat In glass study carrels to watch or listen to Destines. Although the lab broadcasts the audio part of Destines with the use of a sound system, participants had the option of using the lab's headphones to listen to the

telenevela. The headphones reduced peripheral distractions. In addition, the headphones aided the one hearing-impaired student in the afternoon group.

45

Teaching Procedure

Students attended class five days per week. They met with their instructor, a teaching assistant, three days of the week. Of the other two days, one was the lab day, described above. On the other day, Susan Stein,

Associate Professor of Spanish and the First-Year Spanish Supervisor, lectured to the combined sections of 1501 about grammatical concepts. I assumed that the Spanish 1501 students would gain enough syntactical knowledge in their weekly meetings with Stein to be able to get a global understanding of the

Destines episodes.

I divided the students into two groups. The three sections of Spanish

1501 that met at 8 a.m. composed the morning group. The afternoon group included the remaining four sections of 1501. One day per week, Thursday for the morning classes and Friday for the afternoon classes, was designated a lab day. On lab days students met with me in the language learning laboratory for fifty minutes. Attendance at the weekly lab sessions accounted for 10 percent of the students' overall semester grade in Spanish 1501; missed labs were not allowed to be made up. Records of attendance were kept for every weekly meeting. Three sections of the 1501 pupils, approximately 75 participants, met on Thursday mornings at 8:00 a.m.; the other four sections of first-semester

Spanish, made up of about 40 students, fulfilled lab requirements Friday afternoons at 1:00 p.m. Of the roughly 112 students who took Spanish 1501 during the fall semester of 1997, data from only 56 of the participants could be

46

analyzed due to students missing exams, adding the course late or dropping the course before the end of the term.

During our first meeting, all students present voluntarily filled out a survey, called a pre-test, and a questionnaire. Because of the great fluctuation in attendance and class sizes that generally accompanies the first few weeks of classes, students who did not attend class the day that the pre-test survey and questionnaire were filled out had the opportunity to come to my office before our second weekly lab session to complete the forms. Ten students took advantage of this opportunity.

During the first half of the term, the morning group received audio-only instruction while the afternoon group received audio-visual instruction. After the mid-term the morning group received the audio-visual instruction and the afternoon group switched to audio-only instruction. Thus, the morning and the afternoon groups were exposed to both types of instruction. The type of speech participants listened to for both of the types of treatment they received in the lab is called "oral presentation of a fixed, rehearsed script," as defined in Chapter II,

(Byrnes, 1984, p. 319). In addition, this type of speech was non-transactional because the participants listening to and/or watching the videos did not interact with the characters in the videos.

During my weekly meetings with the students, they completed activities that corresponded to the Destines learning series. The first five to ten minutes of each lab session for both the morning and afternoon groups was spent filling

47

out questions in the Preparacidn section provided for each successive episode.

The Preparacidn questions asked students to make predictions about what they thought would happen in the upcoming episode. After each thirty-minute episode of the Destines videos, students spent five to ten minutes answering questions in the ^ Tienes buena memoria? part of the workbook provided for each episode. At the end of the lab period, we discussed the answers to the questions on the ^Tienes buena memoria? pages to review each episode.

Both the morning and afternoon groups were exposed to the same episode of Destines and executed the same workbook exercises on a weekly basis, with one significant difference. For the first half of the semester, the morning students, made up of three sections of Spanish 1501, listened to the

Destines story line only while the afternoon groups, made up of the remaining four sections of 1501, watched and listened to the videos. Students were exposed to the first six episodes of Destines during the first half of the semester.

After six weeks of the morning group's audio-only experience with the soap opera and the afternoon group's audio-visual activity with it, all of the students took the mid-term exam (included in the Appendix).

During the second half of the semester, the morning group had audiovisual access to the telenevela while the afternoon group had audio-only access to Destines. As they had done the previous half of the semester, both groups continued filling out the Preparacidn and ^ Tienes buena memoria? pages of the workbook before and after, respectively, each Destines episode. During the five

48

to ten minutes before and after playing the tapes of the soap opera, I walked up and down the aisles of study carrels to ensure that the members of the classes were completing the tasks in their workbooks. After four weeks of this procedure, the students took the final exam to measure their progress in listening and reading comprehension in Spanish. Participants had four weeks of the second type of treatment, as opposed to the six that they had of the first treatment type for two reasons: (1) the first Destines episode was an introduction to the series with background information which was not a "real" episode; (2) the first few weeks of the semester were confusing for some participants. Students did not have a definite setting for lab sessions until the third week of the semester. Students dropped and added 1501. I did not always have workbooks for new students on their first day of lab and had to wait for more to arrive from the publisher during the first three weeks of the term. The new students also did not understand the lab procedure. The first few lab sessions were less productive than the rest because students were not settled in the lab routine.

The second part of the lab meetings went more smoothly. Participants knew how to fulfill lab requirements, and where to meet, and no new students were included after the period of adding courses ended.

In addition to taking the final exam, participants filled out the post-test survey to ascertain student opinions about the language learning laboratory and which method of learning, audio-only or audio-visual, assisted them most effectively in building listening and reading comprehension skills. The post-test

49

survey included the same statements and Likert scale that the Pre-Test survey had, except that the statements on the Post-Test were in the past tense.

Testing Procedure

Both the morning and afternoon group took the same mid-term and final exams, which measured their competency in listening and reading and the combination of listening and reading in the second language. Students were not allowed to leave the language learning laboratory with any parts of the exams to prevent the morning group from showing the exams to the afternoon group.

The 10-question listening comprehension third of both the mid-term and the final exam required listeners to answer true or false to oral questions about two scripts that they listened to. Questions were oral only to ensure that no skill other than listening was tested.

For the listening/reading portion of the mid-term examination, students listened to two scripts (one provided by Destines on a cassette, the other a recording of a native speaker from Texas Tech and Spanish major from Texas