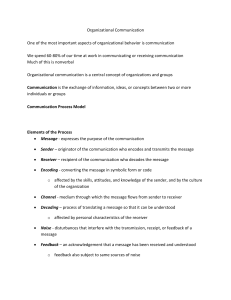

Workplace Communication

advertisement