Civil Wrongs

advertisement

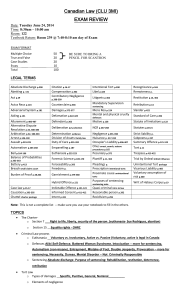

3 CIVIL WRONGS Kenneth A. Krajewski, Esq. * John A. Williamson, Jr., Esq., is author of the chapter which appeared in the first edition of Understanding the Law. Kenneth Krajewski updated the chapter for the 2005 revision. He would like to acknowledge his law clerk, Megan Culliton, for her assistance in updating this chapter. CIVIL WRONGS What Is a “Tort”? A civil wrong occurs when a person’s action, or a failure to take action, causes an injury to another person. The name for this type of wrong is a “tort.” The law calls a failure to take action an “omission.” A tort may be intentional or accidental. In either case, liability for a civil wrong results from one person’s unreasonable interference with the interests of another person. How Does a Tort Differ from a Crime? Although some torts, like assault and battery, might also be punishable under criminal law, there is a difference between criminal and civil wrongs. In a sense, torts are “private” wrongs—breaches of the legal duty we all have to respect the interests of others. Thus, they are different from crimes, which are “public” wrongs in violation of criminal statutes. Criminal cases involve a prosecutor, who is present on behalf of the state, and a defendant. Civil cases involve at least one plaintiff, the person who has been injured, and at least one defendant, the person who did the act or omission causing the injury. Criminal wrongs are punished by fines, community service, or even imprisonment. Victims of civil wrongs are compensated with money for their injuries or damages. The injured person may suffer physical harm, emotional damage, or damage to his or her property. The injured party may not know he or she suffered injury until days, weeks, months or, in some cases, years later. Types of Torts Intentional Torts and Negligence It is not the damage suffered, but rather, the type of act or omission that determines the type of tort. Intentional torts result from deliberate interference with others, such as assault, battery and false imprisonment. Defamation, which is injury to a person’s reputation, is also an intentional tort. Other intentional torts, like trespass, concern an injury to a person’s property interest. As opposed to intentional torts, negligence is an accidental or unintended act or omission which causes injury to another’s person or damage to his or her property. “Negligence” is a legal term used to describe the accidental or unintended result of careless or dangerous behavior. As we have noted, a tort is a civil (non-criminal) wrong, and therefore, it is not the same as a crime. There are, however, circumstances in which a single act may result in both civil and criminal liability. For instance, when one person strikes another, he or she may be subject to criminal prosecution for the act as well as a civil action for any injuries that might result. Although many people believe every injury merits an award of money damages, this is simply not true. Tort law establishes a standard by which all conduct and the resulting injuries are to be measured. To be held responsible for damages, a civil defendant must have 23 UNDERSTANDING THE LAW unreasonably interfered with the interests of another. Damages are only warranted where the plaintiff’s injuries resulted from this interference. The degree of liability also varies greatly, depending on the interest affected, as well as the extent of the harm. Tort law is premised on an intricate network of legal relationships, or duties, between individuals. For a defendant to be held civilly liable for a tort, he or she must have breached a duty owed to the injured party. Many times, the duty involves a responsibility to act in a certain way. Other times, the duty arises from the fact that the act or omission may cause an injury to another. Thus, if the injury is foreseeable, or if it is an anticipated outcome of an act or omission, the duty has been violated. Duties may vary with the circumstances and people involved. For example, the law does not impose the same standard of conduct on children as it does on adults. Likewise, some harmful conduct may be justified or excused when made in response to an emergency situation. One concept that is often repeated throughout the analysis of tort law is whether the injury-causing conduct was “reasonable.” This concept gives rise to much debate among legal scholars and practicing attorneys alike. The meaning and interpretation of the word “reasonable” and its application to tort law will appear as we discuss intentional torts, negligence, and strict liability. Intentional Torts An intentional tort is a purposeful act which causes injury to another. When such a purposeful act is made without a justification or explanation recognized by law, the wrongdoer will be held liable for the injuries caused. Generally speaking, there are two classes of intentional torts. The first pertains to interference with the person, involving damage to the body, reputation, or feelings of another; and the second to interference with another’s property, both real and personal. Interference with the Person Assault and Battery There are many examples to illustrate intentional interference with the body of another. Assault is an example of intentional interference with the person of another: it is the threat of imminent bodily harm or offensive contact which frightens the victim. Assault might be the step right before battery: where a man raises his fists and threatens to punch another man, that action is termed an assault if it is a realistic threat that frightens the man. A victim claiming assault will be able to recover money damages only if his fear of physical harm is reasonable. When the first man follows through and throws a punch, he commits battery. Battery is unpermitted contact between the physical beings of at least two individuals. The perfect example was briefly described above: one person striking another. Although battery is not necessarily an overtly violent action, imagine a barroom brawl when envisioning this tort. 24 CIVIL WRONGS Judging whether the contact rises to the level of the tort of battery, or is merely casual, daily interaction, requires application of the reasonableness standard. While the law protects us from hostile contact, a certain amount of bodily contact is inevitable in daily life, such as nudging in crowded elevators. Consent is assumed for contact like this. False Imprisonment False imprisonment—the unlawful restraint of a person against his or her will—is a third example of interference with the person. False imprisonment is not limited to an individual wrongfully put behind actual bars. Being restrained in a vehicle, or forced to accompany another person, may be considered false imprisonment. Sufficient restraint may be effected by physical barriers, such as a fence, or by real or threatened acts of force. Sometimes, words alone may suffice—i.e., when a person claiming legal authority says, “I arrest you!” Equally important to the confinement, is that the restrained person know of it or be harmed by it. The restraint must be complete; mere obstruction of someone’s right to go where he or she pleases does not constitute false imprisonment. Similarly, it is not false imprisonment when a construction crew blocks public thoroughfares with sawhorses, causing motorists to use alternate routes. The possibility of false imprisonment may arise with the detention of a suspected shoplifter. When a merchant detains a suspected shoplifter, it must be done with caution to avoid liability for an intentional tort. The detention must be based on a reasonable belief that shoplifting actually occurred. Restraint must be limited to a reasonable period of time, and accomplished in a sensible manner. Provided merchants meet these conditions, they have a limited privilege to detain suspected shoplifters for the purpose of investigation. Again, assessment of a plaintiff’s ability to recover under this tort theory revolves around whether the person’s reaction was that of a reasonable person. If the restraint is conducted in a manner that would not upset or intimidate a reasonable person, a hypersensitive plaintiff will likely not recover. However, when a department store restrains an elderly man, based on flimsy suspicions, and forcibly removes him to a locked room for several hours of questioning, the tort of false imprisonment has probably occurred, and this plaintiff may be entitled to recover money damages. Intentional Infliction of Emotional Harm One may also interfere with the person of another by intentionally inflicting emotional harm. To do so, the injuring party must exceed the bounds tolerated by a decent society in causing serious distress to another. Only extreme, outrageous, or intolerable conduct will suffice, since liability is not extended to include trivial insults or mere profanity. Mere rude behavior does not generally rise to the level of tortious conduct. Plaintiffs may not recover money damages because their feelings have been hurt, they have been made unhappy, or have suffered some minor humiliation. Once again, the test is whether a reasonable person would respond to the offensive behavior with a similar reac- 25 UNDERSTANDING THE LAW tion. Actionable intentional infliction of emotional harm may occur, for instance, when a person is falsely told her child has committed suicide. As with all other areas of tort law, extreme sensitivity of the offended party is not taken into account when considering whether intentional infliction of emotional harm has occurred. To establish liability, there must be substantial or prolonged mental anguish characterized by such highly unpleasant reactions as fright, horror, or grief. Because of this high standard, it is often difficult to sustain a claim of intentional infliction of emotional harm. Interference with Property Trespass onto Property The deliberate interference with property is another class of intentional tort. A common example is trespass, which is the purposeful entry without permission on someone else’s real estate. Trespass is a tort because it interferes with the right of the owner to have exclusive possession of his or her property. Trespass is not contingent on entry by a person; even flooding a neighbor’s lot may constitute trespass. The tort of trespass requires that the trespasser occupy the challenged property through a deliberate, conscious or purposeful act. Intent to arrive on the property is all that is necessary. The trespasser does not have to be aware he is on someone else’s property. Many people believe that a sign or fence is necessary to alert potential trespassers of property boundaries. However, even without physical markings of the property’s edges, if someone is on another person’s land without permission, it is a trespass. An owner has the right to exclusive use of his or her property for several feet above, and below, the ground. For instance, a child’s ball that flies across another’s property, four feet above the ground and never touching an inch of land, is a trespass. Property owners are equally protected from the erection of overhanging buildings on adjacent lots. The entry must actually be physical, however. Allowing light into a neighbor’s yard does not constitute trespass, nor does playing loud music or allowing foul odors to cross property lines. Recovery of money damages for trespass is not permitted when the owner has consented to entry on property, such as an easement granted a telephone company to string wires across a field. Interference with Personal Property Intentional interference with the personal property of another is an intentional tort. In law, personal property is often referred to as “chattels.” A chattel is any tangible object that can be owned by an individual, with the exception of land and buildings. Chattels include such items as automobiles, clothing, and documents (stock certificates, bankbooks, insurance policies). Interference may consist of damage, alteration, destruction, unauthorized use or deprivation. Merely handling the property of another without harming its usefulness does not constitute interference. Even a slight harm, such as taking a key to the side of someone else’s 26 CIVIL WRONGS vehicle, would likely warrant damages only for the cost of repairs. Dispossession or destruction of the property, however, would be sufficient to warrant more extensive money damages. For example, as opposed to keying the vehicle, taking a sledgehammer to the vehicle might merit full replacement value as damages. Defenses There are several defenses to interference with the person or property of another. Consent is a defense to all intentional torts; no one will be held liable if the other party knowingly and freely agreed to the interference. So, there can be no action for trespass when someone is invited onto property. Similarly, no action can be brought when an automobile is loaned by the owner and used within the bounds of the consent. Implied Consent In some situations, the customary nature of an activity may imply consent to interference. For example, participants in athletic events accept physical contact as long as it is consistent with the rules. Similarly, operating a store open to the public invites regular “invasions.” Here, too, consent is implied. “Privilege” Another defense is privilege, which may be used where particular circumstances justify conduct. This defense arises when certain conduct occurs out of necessity. The person acting is permitted to take this otherwise prohibited action, because of its significant social value. An example is the arrest of a suspect by a police officer. Self-Defense An individual can claim self-defense and defense of others when explaining his or her actions. To establish a protective privilege, the individual must show that the timing is correct: the threat to the individual or someone else is imminent. Revenge is not a proper explanation for the use of “self-defense.” Also, the person claiming self-defense must demonstrate that the threat is genuine. The person under attack must react in a reasonable way. This privilege is limited to the force necessary to stop the attack. For example, an individual about to be slapped may not pull out a gun to stop the attacker. Only a genuine and imminent threat to human life justifies use of deadly force. New York takes this limitation one step further, and requires a person under attack to retreat from the danger before using deadly force. Generally, in situations involving an attack, one person is entitled to come to the defense of another. In so doing, he or she assumes the other’s right to self-defense and may do whatever the other might do for self-protection. Necessity and Other Limits on Protecting Property Because owners have the right to the peaceful enjoyment and use of their real property, they are entitled to defend it based on a principle similar to that of self-defense. The right to defend personal property is more limited, however, because the social value accorded to 27 UNDERSTANDING THE LAW possessions is considerably less than that given to the well-being of persons. Thus, no one may use deadly force to protect property, regardless of value. For example, a homeowner going out of town for an extended trip cannot set spring-loaded guns to fire in the event someone attempts to break into the unoccupied house. This force is unreasonable, and the homeowner would very likely be liable for money damages for any injuries caused, even to a burglar. The only time excessive or deadly force is permitted to protect a home occurs when the people inside the home are in serious risk of harm as well. There are occasions where interference with property is permitted, and in fact, encouraged. A defense known as “necessity” arises when an individual attempts to prevent serious harm to a human being, including himself or herself. This is known as private necessity. For example, an individual operating a single-engine plane is forced to make a crash landing in a farmer’s crop fields. As a result, the crops are destroyed. Although technically this is a trespass to chattels, the pilot can defend his actions by explaining the necessity of the crash landing. While he will likely be liable for the value of the destroyed crops, the pilot will not be liable for damages due to trespass. In the above example, take note that the farmer cannot prevent the pilot from using her fields as a refuge. Although in most circumstances the trespasser may be chased off of private property, a genuine emergency requires the farmer to allow the pilot to remain until the emergency ends. Public necessity is very similar to the private variety but, as the name indicates, involves preventing harm to the public at large. A common example involves a man forced to shoot a neighbor’s rabid dog before it attacks a nearby group of small children. Although the man interfered with his neighbor’s property, in fact killing his neighbor’s dog, he did so to prevent public harm. Most likely, this man will not be liable to the neighbor for the value of the dog. Defamation One tort that often appears grouped with intentional torts is defamation. “Defamation” is damage to a person’s reputation by means of a false statement. To establish defamation, the individual must have made a defamatory statement specifically identifying the injured party. Certain topics of criticism are considered more sensitive than others, and more likely to be defamatory. These include statements about a person’s skills or ability to practice in his or her profession; statements claiming that an individual committed a crime of moral turpitude; or statements claiming that an individual is unchaste. New York law also recognizes that a false allegation that an individual is homosexual may be defamatory. Even with these categories of defamation, however, the statement must be “published,” that is told to another. If only the person being defamed knows of the allegation, it is not defamation! A written defamatory statement is libel. If the defamatory statement is spoken, it is slander. Because of its spoken nature, slander is more difficult to prove than libel. 28 CIVIL WRONGS The defamed individual must be alive: dead people cannot be offended by defamatory statements. Mere name-calling does not usually constitute defamation. Opinions might be defamatory depending on the tone, context and purpose with which they are spoken. Inadvertent publication is still actionable. Persons accused of defamation have three defenses. They may claim consent; they may also claim truth of the statements. Finally, an accused defamer may claim privilege. Types of privilege include privileges between spouses, and statements made by government officials regarding their office and official duties. Negligence In the legal world, commission of a negligent tort requires the following: a duty between the parties, breach of that duty, proximate cause, and damages. This seemingly complicated definition is actually very simple. The individuals involved must have a legal relationship of some sort, and that relationship raises a duty to act in a reasonable way. One of the parties violates that relationship and by doing so, causes the other an injury. The injuring party must have known, or should reasonably have known, that the actions would cause some sort of injury. By definition, negligent people do not intend the harm resulting from their actions. Rather, they engage in conduct carrying risks which a reasonable person is expected to anticipate and avoid. Obviously, life cannot be free of accidents, so a person is not necessarily liable for negligence because conduct may place others at risk. Many activities such as driving a car, flying in an airplane, or even riding a bicycle involve some risk. The issue in negligence cases is to determine whether the injuring party should have foreseen the possible risks to others as a result of even seemingly mundane activities. Duty Who is a foreseeable victim? The concept of a duty of care defines a level of social relationships which act as a guide for foreseeability. It is this concept of duty that establishes whether an individual is in a position of risk which requires him or her to exercise reasonable care toward others. In order to determine whether a duty of care exists and has been breached, the law hypothesizes a standard of conduct which a “reasonable” person would follow under the circumstances. “Reasonable Person” Standard and “Duty of Care” The reasonable person standard obliges us all to take such precautions as everyday prudence demands. It represents the community’s judgment as to how a reasonable individual should behave in situations where there is risk to others. Thus, everyone who drives a vehicle is expected to do so with reasonable care. Speeding in congested areas or operating a vehicle with defective brakes are examples of substandard or negligent conduct by which a motorist breaches a duty of care to others. 29 UNDERSTANDING THE LAW Circumstances may impose varying standards for the duty of care, allowing for limited exceptions to the harsh rule. Superior knowledge will be considered in determining the reasonableness of an individual’s actions. For example, professionals in medicine, law, architecture, and other licensed disciplines are held to standards of care commensurate with their respective fields of training and employment. A doctor who specializes in a particular branch of medicine will be held to a higher standard within that specialty than a general practitioner. In addition, physical characteristics are considered if necessary, and only if relevant. For instance, a person’s status as physically disabled may affect a determination of the reasonableness of his or her actions. In some situations, custom in a particular community may provide an indication of what constitutes reasonable care. Still, the observance of local custom does not always imply freedom from negligence since the customary activity may fall below the level of reasonableness. For instance, it may be customary in some cities for taxi drivers to tailgate, but this does not necessarily make the conduct reasonable or absolve a tailgating taxi driver from liability if an accident occurs as a result of such behavior. Duty to Act An individual passing by an accident caused by that tailgating taxi cab driver has no affirmative duty to stop and help the injured parties. However, should that individual choose to stop and help rescue an injured party, he or she has a duty to act reasonably and with due care. In addition, New York has a Good Samaritan rule, which protects certain individuals from liability, should further injury occur while they attempt to rescue another. This exception is limited, however, to a nurse, doctor or veterinarian engaged in voluntary rescue. Though there is rarely a duty to act affirmatively in the absence of a legal relationship, an individual who causes a dangerous situation may have a duty to rescue the person he or she put in harm’s way. For example, if a woman throws a child who cannot swim into the deep end of a pool, she likely has a duty to rescue that child from drowning. Some legal relationships impose a pre-existing duty of care requiring an individual to act to rescue. For example, common carriers like airlines and bus companies, and hotels generally have a duty to rescue individuals who put themselves into the company’s care. Similarly, manufacturers who encourage people to buy their products assume a duty to protect purchasers from defects in a manufactured item which might cause injury. Thus, a manufacturer may have a duty to recall a defectively manufactured product already in the marketplace. “Proximate Cause” To create liability, the breach of duty must be the proximate cause of the injury. “Proximate cause” is simply a phrase which asks, “How fair is it to impose liability under these factual circumstances?” The law requires a reasonable relationship between a negligent act and its harmful consequences. 30 CIVIL WRONGS For example, suppose a driver ignores a stop sign and collides with another vehicle. Obviously, there is a relationship between the driver’s failure to stop and the subsequent collision. Thus, it can be said that the driver’s failure to stop caused the collision. In other words, the failure was the cause of the consequences, and there can be no question as to whether those consequences were foreseeable. As such, the driver will be liable for any injuries sustained by the occupants of the other vehicle. On the other hand, suppose that a bystander, unrelated to any of the occupants of the vehicles, is startled by the sound of the nearby collision and spills a cup of hot coffee on her lap, causing her to be burned. The law holds that such consequences, though harmful, are too remote to be considered to have been caused by the driver’s failure to stop at the stop sign. Injury As a final element of negligence, the injured party must demonstrate that he or she suffered an injury as a result of the dangerous activity engaged in by the injuring party. For example, if the occupants of the car hit by the vehicle that ignored a stop sign suffer injury, the relationship between their injuries and the negligent acts of the driver are clear. If the occupants do not suffer any injury, they may not recover money damages merely because the accident occurred. Interestingly, New York courts require negligent parties to be liable for all consequences of their actions. This is the case even if the injured party is especially vulnerable to injury, or prone to sickness. In the car accident example, imagine that one of the vehicle occupants already had a broken leg before the accident. If the collision in question causes a more severe fracture, and permanently disables that passenger, the driver is liable for all injuries sustained as a result. If the negligent driver was lucky enough to cruise through the stop sign at an intersection without hitting any other vehicles, and caused no injuries, the driver would not be civilly liable for money damages to anyone. Defenses As with intentional torts, there are defenses to negligence actions and limitations on liability. Contributory negligence is one such defense. This doctrine requires that the plaintiff (injured party) bringing the suit must have exercised reasonable care in guarding his or her own well-being. If this obligation was breached and caused injury to the plaintiff, he or she would be considered contributorily negligent. Thus the doctrine imposes the same standard of reasonable care on the plaintiff as it does on the defendant. Using the example of the negligent driver, assume that the driver strikes a woman crossing the street instead of another car. Under this doctrine, it is significant whether the pedestrian took reasonable precautions in entering the street. If not, she would be considered to have been careless and thereby to have contributed to her own injury. 31 UNDERSTANDING THE LAW Traditionally, common law excused entirely a negligent defendant from liability when there was contributory negligence on the part of the plaintiff, and acted to bar completely any recovery. However, a rising dissatisfaction with this “all or nothing” doctrine has led to the adoption of another concept: comparative negligence. Under this doctrine, which became applicable to all claims of negligence occurring in New York after September 1, 1975, culpable conduct on the plaintiff’s part does not bar recovery completely; rather, it is reduced in proportion to the amount of negligence on the part of the plaintiff which contributed to the injury. “Assumption of risk” is still another doctrine which may affect recovery of damages. Generally, it bears the same relationship to negligence as does consent to intentional torts. It becomes operative as a defense when the plaintiff can be shown to have been knowingly and voluntarily exposed to the risk which resulted in injury. The key element, of course, is the knowing and voluntary nature of the exposure. When a person buys a ticket to a baseball game and sits along the third base line, there is an assumption of the risk of being hit by a foul ball. Assumption of risk is not a total defense to an action if the accident happened on or after September 1, 1975. Rather, like contributory negligence, assumption of the risk is a type of comparative negligence which reduces recovery in the proportion that the plaintiff’s voluntary exposure to risk of injury bears to the culpable conduct which caused the damages. Strict and Statutory Liability Strict Liability Strict liability is an area of tort law which involves neither intentional harm nor lack of reasonable care. Generally, liability is imposed because the activity in which the defendant engages is so inherently dangerous that the law holds that person entirely accountable, despite safety precautions. The best example of strict liability involves ultra-hazardous activities. To identify an ultra-hazardous activity, look for three criteria. First, the activity cannot be made safe; second, it poses a risk of severe harm; and third, the activity must be uncommon in the community. To get a mental picture of this tort, imagine blasting or the use of explosives or anything involving chemicals, or any activity involving nuclear energy or radiation. Any party engaged in these types of activities may be strictly liable for resulting harm. Injuries caused by animals also fall under this category. The owner of a domesticated animal who has knowledge of his pet’s vicious propensity to bite people may be strictly liable for injuries caused by that pet. The first bite is generally actionable under a negligence theory of recovery. However, the owner is strictly liable for the second bite, and any subsequent bites. Owners of non-domesticated or wild animals are strictly liable for all injuries caused by those animals. 32 CIVIL WRONGS Statutory Liability Statutory liability is similar in that there is no need for the injured party to demonstrate intentional or negligent harm. All that must be shown is that the defendant’s activity caused harm to an interest protected by a statute. A prime example of this type of liability is the Workers’ Compensation Law, which enables injured employees to recover for injuries sustained while in the course of their employment. In a sense, the employer is strictly liable for an employee’s injuries, because the employer’s insurance pays for resulting medical bills and a portion of lost wages without regard to fault. This recovery is limited, however, to actual damages. An injured worker may not recover punitive damages or recover for pain and suffering from his or her own employer. Also, although the employee is free to sue anyone else, the employee is barred from suing the employer under this statutory scheme. In New York, the law imposes liability on bar owners, hotel management, innkeepers, and others who sell or dispense alcoholic beverages. Under this law, liability attaches when the establishment illegally sells liquor to a minor, or to someone who is already intoxicated, and who thereafter proceeds to cause injury to a third party. In this instance, it is not necessary to show negligence on the part of the vendor. Deprivation of constitutional rights may also give rise to a right of action. There are state and federal statutes which protect against deprivation of personal rights secured to individuals by the Constitution and which provide a remedy in civil damages against those infringing the plaintiff’s rights. Product Liability Another form of strict liability is the liability of a product manufacturer for injury caused by its malfunctioning or defective product. The key concept with respect to a product liability claim is that the injured party must establish that the product is defective. A product may be defective if it has a manufacturing flaw, a design defect, or inadequate warnings with respect to its use. A manufacturing flaw may be the result of an error in the product’s manufacture. Such a product, therefore, does not operate as the manufacturer intended. Manufacturers generally have a duty to inspect products for manufacturing flaws. A design defect, instead, occurs when a product is manufactured in accordance with its design, but such design itself endangers the product’s users. Design defects must pose an unreasonable risk to users. A claim of inadequate warnings involves a failure of the designer or manufacturer to warn the user of latent or concealed dangers associated with use of the product. Retailers and distributors may also be strictly liable for the sale of a defective product. Depending on the circumstance, a product liability claim may also contain elements of negligence and breach of contract. 33 UNDERSTANDING THE LAW Going to Court When a person has been the victim of an intentional tort, has suffered as a result of negligence, or has a claim under strict liability, he or she may seek to recover compensation in the form of damages from the other party. Frequently, the process involves a lawsuit. First, the plaintiff (injured party), acting through an attorney, serves a summons and complaint on the defendant (the injuring party). This initiates the legal action, informing the defendant of the nature of the claimed injury. In response, the defendant serves an answer, which contains the defendant’s position on the issues and includes all available defenses. Once the plaintiff commences the case, and the defendant becomes involved in the action, the process of discovery begins. ”Discovery” consists of the exchange of relevant documents in response to demands. Such demands include production of medical reports and the sworn testimony of witnesses. In addition, several proceedings, such as motions, examinations before trial, and non-party depositions are now available to both parties. Through these devices, litigants develop evidence in support of their respective positions and determine whether the other side has a legally sufficient case. Throughout the discovery process, the parties may negotiate to reach an agreement about the value of the case. If a settlement cannot be reached, the case goes to trial. The plaintiff must prove the case by a fair preponderance of the credible evidence which is composed of the testimony of witnesses and relevant exhibits. The defendant counters by similar means. After both sides have presented their cases, the judge instructs the jury regarding the applicable law (unless trial by jury has been waived and the case is tried before the judge alone). After receiving the judge’s instructions, the jury deliberates. If it finds in favor of the plaintiff, it will also determine the amount of damages to be awarded. Damages generally fall into three categories: (1) compensatory; (2) punitive; and (3) nominal. The first is intended to make the plaintiff “whole,” i.e., fully compensated, for the loss suffered. Compensatory damages may include awards for medical expenses, pain and suffering, and loss of earning capacity. Punitive damages constitute punishment for wrongdoing, and are available in cases where the defendant has acted intentionally or recklessly to harm the plaintiff. Nominal damages are characteristically small in amount and are awarded in cases of intentional tort to establish on the public record that the defendant has wronged the plaintiff. Their purpose is to induce victims of torts to seek satisfaction by legal means rather than resorting to retaliation outside the law. Alternatives to Court Due to the congestion of many courts’ dockets, and the expenses and uncertainty associated with a trial, many litigants opt for alternative dispute resolution (ADR) procedures. ADR may involve mediation by a trained mediator or an arbitration proceeding before one 34 CIVIL WRONGS or more arbitrators hired by the parties to hear the case. Mediators and arbitrators are usually attorneys that are highly skilled in the area of law that the case involves. Though most litigants choose to engage in ADR voluntarily for the reasons above, many courts now have mandatory ADR programs which the parties must attend before the case will be scheduled for trial. That being said, it is a long road to reach the point where damages are determined. The elements of a claim must be established methodically to determine what amount, if anything, to which the plaintiff is entitled. 35