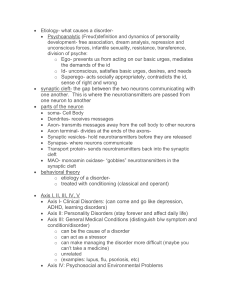

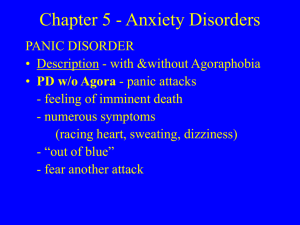

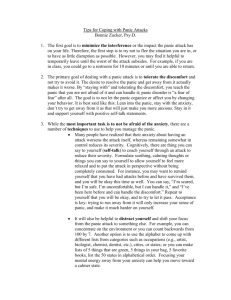

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

advertisement