Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Cereal Science

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jcs

Retrogradation of waxy and normal corn starch gels by temperature cycling

Xing Zhou a, Byung-Kee Baik b, Ren Wang c, Seung-Taik Lim a, *

a

Graduate School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Korea University, Seoul 136-701, Republic of Korea

Washington State University, Department of Crop & Soil Sciences, Pullman, WA 99164-6420, USA

c

Department of Food Science & Technology and Carbohydrate Bioproduct Research Center, Sejong University, 98 Gunja-Dong, Gwangjin-Gu, Seoul 143-747, Republic of Korea

b

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 1 June 2009

Received in revised form

10 September 2009

Accepted 22 September 2009

Gelatinized waxy and normal corn starches at various concentrations (20–50%) in water were stored

under temperature cycles of 4 C and 30 C (each for 1 day) up to 7 cycles or at a constant temperature of

4 C for 14 days to investigate the effects of temperature cycling on the retrogradation of both starches.

Compared to starches stored only at 4 C, both starches stored under the 4/30 C temperature cycles

exhibited smaller melting enthalpy for retrogradation (DHr), higher onset temperature (To), and lower

melting temperature range (Tr) regardless of the starch concentration tested. Fewer crystallites might be

formed under the temperature cycles compared to the isothermal storage, but the crystallites formed

under temperature cycling appeared more homogeneous than those under the isothermal storage. The

effect of starch content on the retrogradation was greater when the starch gels were stored under cycled

temperatures. The reduction in DHr and the increase in conclusion temperature (Tc) by retrogradation

under 4/30 C temperature cycles became more apparent when the starch concentration was lower (20 or

30%). Degree of retrogradation based on melting enthalpy was greater in normal corn starch than in waxy

corn starch when starch content was low.

Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Temperature cycling

Retrogradation

Corn starch

1. Introduction

The starch granule, commonly composed of both amylose and

amylopectin, is semicrystalline. The crystalline regions in granules

appear in clusters of branched amylopectin chains. Amylose,

mainly linear starch chains, is largely amorphous and randomly

distributed between amylopectin clusters (Bemiller, 2007). When

the starch granule is heated in the presence of water, the semicrystalline structure in granules transforms to an amorphous form;

this process is termed gelatinization. Gelatinized starch, however,

tends to re-associate in an ordered crystalline structure during

storage, which is termed retrogradation (Yuan et al., 1993).

As the retrogradation of starch affects the acceptability and shelf

life of starchy food, its control in rate and degree has been

substantially studied by food scientists. Starch retrogradation

occurs in three phases: nucleation, i.e. formation of critical nuclei;

propagation, i.e. growth of crystals from the nuclei formed; and

maturation, i.e. crystal perfection or continuous slow growth. The

Abbreviations: DR, the degree of retrogradation; DSC, differential scanning

calorimeter; Tc, conclusion temperature; To, onset temperature; Tp, peak temperature; Tr, melting temperature range; DH, melting enthalpy; DHg, melting enthalpy

for gelatinization; DHr, melting enthalpy for retrogradation.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ82 2 3290 3435; fax: þ82 2 921 0557.

E-mail address: limst@korea.ac.kr (S.-T. Lim).

0733-5210/$ – see front matter Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2009.09.005

overall crystallization rate mainly depends on the nucleation and

propagation rate (Eerlingen et al., 1993). A temperature near the

glass transition temperature favors nucleation, whereas a higher

temperature up to the melting temperature favors propagation

(Baik et al., 1997; Durrani and Donald, 1995; Silverio et al., 2000).

When the storage temperature of gelatinized starch was cycled

between the temperature for nucleation and the temperature for

propagation, the rate of retrogradation could be accelerated

(Bemiller, 2007; Slade et al., 1987). This type of temperature cycling

process that induces a stepwise nucleation and propagation

promotes the growth of crystalline regions and perfection of crystallites (Silverio et al., 2000).

The degree of starch retrogradation and the property of the

starch crystallites formed are influenced not only by the storage

time and temperature, but also by starch concentration (Jang and

Pyun, 1997; Liu and Thompson, 1998; Longton and Legrys, 1981)

and the botanical origin of the starch, i.e. starch crystallinity,

molecular ratio of amylose to amylopectin and structures of

amylose and amylopectin molecules (Elfstrand et al., 2004;

Fredriksson et al., 1998; Jane et al., 1999; Klucinec and Thompson,

1999; Lai et al., 2000; Russell, 1987a; Sasaki et al., 2000; Vandeputte

et al., 2003; Varavinit et al., 2003). Several studies have investigated

starch gelatinization or retrogradation behavior as a function of

a wide range of moisture content. It was generally agreed that

maximum retrogradation enthalpy occurred at the so-called

58

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

intermediate water level when the starch concentration was 40–

60%, but the precise relationship between starch concentration and

retrogradation enthalpy varied according to storage temperature

(Jang and Pyun, 1997) and starches of different origin (Liu and

Thompson, 1998). Silverio et al. (2000) have investigated the effect

of temperature cycling on the retrogradation of amylopectins isolated from 10 different starches. Park et al. (2009) found that 40%

waxy corn starch gel retrograded at the cycled temperatures had

a larger amount of resistant starch but remained softer than those

stored at 4 C. However, the influences of amylose content and

starch concentration together with temperature cycling on starch

retrogradation have not been reported.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) has been widely used to

study the thermal behavior of starch gelatinization and retrogradation. The DSC melting endotherm of starch provides the enthalpy

as well as temperatures for melting the crystalline structure in

starch, which reflects the degree and perfection of the crystallinity

(Durrani and Donald, 1995). The melting enthalpy (DH) is often

positively related to the amount of crystals (double or single helical

structure) of the starch (Liu et al., 2006). The onset temperature (To)

represents the melting temperature of the least stable crystallites.

The peak temperature (Tp) suggests the melting temperature for

the majority of starch crystallites. The conclusion temperature (Tc)

indicates the melting temperature of the most perfect crystallites.

The melting temperature range (Tr), i.e. TcTo, indicates the degree

of heterogeneity of the crystallites (Biliaderis, 1992). The higher the

melting temperature (To, Tp, Tc) and the narrower the melting

temperature range (Tr), the more stable and uniform the crystallites

are (Durrani and Donald, 1995).

In this study, temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1

day, together with various starch concentrations (20–50%) were

used to investigate the effects of temperature cycling and starch

concentration on the retrogradation of waxy and normal corn

starches. Crystallinity in the retrogradated starches was evaluated

in the terms of melting enthalpy and temperatures using DSC.

2. Experimental

heating at 105 C for 5 h. Both starches contained crude protein less

than 0.35%, and ash less than 0.15% (manufacturer’ data).

2.2. Gelatinization and retrogradation

The starch (dry solid) was weighed into an aluminum DSC pan

and distilled water was added until the starch was fully wet. The

excess moisture was allowed to evaporate in a balance until the

total weight of starch and water reached 10 mg to achieve the

desired starch concentration of 20, 30, 40 or 50%. The pan was

hermetically sealed, and equilibrated for 24 h at 4 C.

After equilibration the DSC pans were heated in a convection

oven for 15 min at 105 C to gelatinize the starch (Silverio et al.,

2000). After cooling to room temperature (30 min), the DSC pans of

gelatinized starch were stored for 14 days under two different

conditions: at constant 4 C (stored in the cold chamber), or under

the temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1 day (4/30 C).

For temperature cycling, after storage in the cold chamber at 4 C for

1 day, the DSC pans were immediately taken out and stored in

a convection oven kept at 30 C for 1 day, and then this step was

repeated.

2.3. DSC analysis

A differential scanning calorimeter (DSC6100, Seiko Instruments

Inc., Chiba, Japan) was used to determine the thermal characteristics of starch gelatinization and retrogradation. To determine

gelatinization characteristics, the equilibrated DSC pans were

directly heated by DSC from 20 to 120 C at a rate of 5 C/min. For

retrogradation properties, the DSC pans of retrograded starches

were heated under the same conditions every 2 days or after each

temperature cycle. Indium and mercury were used for temperature

calibration, sapphire was used for heat capacity calibration, and an

empty pan was used as a reference. All measurements were performed in triplicate. The respective enthalpy (J/g) was expressed on

a dry starch weight basis. The degree of retrogradation (DR) was

calculated as the ratio of enthalpy of retrogradation to enthalpy of

gelatinization.

2.1. Materials

2.4. Statistical analysis

Waxy and normal corn starches were gifts from Samyang Genex

Company (Seoul, Korea). The moisture content of waxy corn starch

was 13.2% and that of normal corn starch was 12.6%, determined by

All numerical results are averages of at least three independent

replicates. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance

Normal

Waxy

20%

(14.4J/g)

30%

(14.5J/g)

Endothermic Heat Flow

20%

(16.4J/g)

30%

(17.6J/g)

40%

(14.7J/g)

40%

(18.5J/g)

50%

(15.0J/g)

50%

(19.6J/g)

M2

M1

0.1m W

20

40

G

60

80

M1

100

Temperature (°C)

0.1m W

120

20

G

40

60

80

100

120

Temperature (°C)

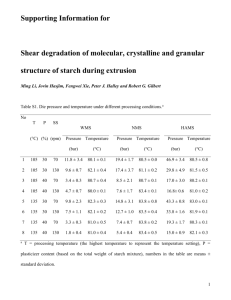

Fig. 1. DSC gelatinization thermograms of waxy and normal corn starches at various concentrations in water. Data in brackets are values of melting enthalpy for gelatinization (DHg).

Each value is the mean of triplicate measurements.

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

A

59

Normal

Waxy

Endothermic Heat Flow

2d

2d

20%

14d

20%

14d

2d

2d

30%

14d

14d

2d

30%

2d

40%

14d

14d

40%

2d

50%

2d

14d

50%

14d

0 .1 m W

20

30

0 .1 m W

40

50

60

70

20

80

30

Temperature (°C)

B

40

50

60

70

80

Temperature (°C)

Waxy

Normal

1cycle

1cycle

20%

Endothermic Heat Flow

7cycles

1cycle

20%

7cycles

30%

1cycle

7cycles

30%

1cycle

7cycles

40%

1cycle

7cycles

40%

7cycles

1cycle

50%

1cycle

7cycles

50%

7cycles

0.1mW

20

30

0.1mW

40

50

60

70

80

Temperature (°C)

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Temperature (°C)

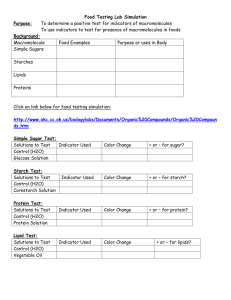

Fig. 2. (A) DSC thermograms of waxy and normal corn starches retrograded at 4 C for 2 and 14 days at various starch concentrations; (B) DSC thermograms of waxy and normal

corn starches retrograded for 1 and 7 temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1 day at various starch concentrations.

(ANOVA) using ORIGIN 8.0 (OriginLab Inc., USA). The statistical

significance were determined by Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. DSC thermograms for gelatinization

For both waxy and normal corn starches, notable changes in the

DSC thermograms of starch gelatinization occurred when starch

concentration increased (Fig. 1). Multiple endothermic peaks were

observed when the starch concentration was above 40%. While the

endothermic peak (G) around 70 C remained relatively unchanged,

the peak (M1) between 80 and 100 C and the peak (M2), which

appeared at above 100 C in normal corn starch, became more

evident and moved to higher temperatures when the starch

concentration increased. The G and M1 endotherms were associated with starch gelatinization, which occurred by the disruption of

amylopectin double-helices, whereas the M2 endotherm appeared

at above 100 C in normal corn starch was due to the melting of the

amylose–lipid complex (Donovan, 1979; Evans and Haisman, 1982;

Garcia et al., 1997; Jang and Pyun, 1996; Liu et al., 2007; Russell,

1987b). Amylopectins in waxy and normal corn starches have

similar structure profiles (Jane et al., 1999), however the melting

enthalpy for gelatinization (DHg, calculated by the G or G þ M1

endotherm size, depending on the starch concentration) of normal

corn starch was smaller than waxy corn starch at all starch

concentrations tested (Fig. 1), which was probably due to less

amylopectin content in normal corn starch than in waxy corn

starch. There has been much controversy in trying to explain the

presence of the two endotherms (G and M1) for starch gelatinization. Some authors (Donovan, 1979; Evans and Haisman, 1982;

Russell, 1987b) attribute the existence of the two transitions taking

place at different starch contents to heterogeneity in water distribution. Biliaderis et al. (1986) suggests a partial melting, followed

60

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

80

Waxy

Waxy

Normal

Normal

70

60

50

Melting Temperature (°C)

40

30

20

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Storage Time (days)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Temperature Cycles

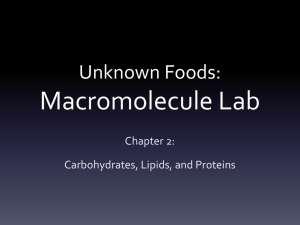

Fig. 3. Onset temperature (To) (open symbol) and the conclusion temperature (Tc) (solid symbol) of waxy (upper) and normal (lower) corn starches at various concentrations: 20%

(square), 30% (round), 40% (up triangle) and 50% (diamond). Starches were retrograded at 4 C for 14 days (left) or under the temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1 day

up to 7 cycles (right).

by reorganization (crystallite perfection) and final melting of perfected crystallites in a DSC scan. Since starch crystallite perfection is

a slow process, it is less likely to occur in a short time, such as

during the DSC scan. Garcia et al. (1997) used SEM and TEM to

observe the structural changes of cassava starch granules during

gelatinization and illustrated that a competition of granules for

water during heating would take place when the starch concentration was high. In other words, the presence of the two endotherms (G and M1) indicates heterogeneity in water distribution

during starch gelatinization. Starch may solubilise in different

manners when its moisture content is changed. After gelatinization, the heterogeneous distribution of water as well as some water

limitation among the starch molecules might influence the rate and

degree of starch retrogradation too.

3.2. DSC thermogram for retrogradation

Waxy and normal corn starches retrograded at a constant

temperature of 4 C exhibited broad endotherms at all concentrations tested (Fig. 2A). The shapes of these retrogradation endotherms varied as a function of starch concentration. After storage

for 2 days, the main peak was observed at about 55 C for 20% waxy

corn starch, moving to a higher temperature as starch concentration increased. A lower-temperature shoulder was apparent for

waxy corn starch of 40% and 50% concentration. After further

storage to 14 days, the major peak after the first 2 days storage was

still evident, but the region of the former lower-temperature

shoulder was much enhanced, becoming the main peak for 40% and

50% waxy corn starch. For 20% and 30% waxy corn starch, only one

peak was apparent, shifting to lower temperatures as the storage

time increased. These observations are in agreement with the

results of Liu and Thompson (1998). The retrogradation thermogram for normal corn starch stored under 4 C was similar to that for

waxy corn starch. However, a main peak and a low temperature

shoulder were only apparent in 50% normal corn starch, and the

peak temperature was lower than that of waxy corn starch.

A broad distribution of the endotherm may indicate the

heterogeneity of retrograded starch crystallites. The development

of a lower-temperature shoulder or the shift of peak temperature to

lower temperature indicates that the increase of the endotherm of

retrograded starch during storage at 4 C largely results from the

growth of less perfect crystallites.

When the starch gels were stored under the 4/30 C temperature

cycles, the thermograms of the retrograded starches exhibited

narrower peaks than those for the starch isothermally retrograded

at 4 C, regardless of concentration (Fig. 2B). It indicates that the

crystallites formed under temperature cycles were more homogeneous than those formed under a constant 4 C. The endothermic

peak for melting of the retrograded starch became larger with the

increase in concentration. Contrary to the starch stored at

a constant 4 C, the peak melting temperature of retrograded starch

at the cycled temperatures increased during storage. Therefore it

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

61

45

Waxy

Waxy

Normal

Normal

40

35

30

Melting Temperature Range (°C)

25

20

15

10

5

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Storage Time (days)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Temperature Cycles

Fig. 4. Melting temperature range (Tr) of retrograded waxy (upper) and normal (lower) corn starches at various concentrations: 20% (-), 30% (C), 40% (:) and 50% (A). Starches

were retrograded at 4 C for 14 days (left) or under the temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1 day up to 7 cycles (right). Starch of 30% concentration retrograded at 4 C

(B) was included for comparison.

appears that more stable crystallites were formed under 4/30 C

temperature cycled storage.

3.3. Melting temperatures for retrogradation

The melting temperature of retrograded waxy and normal corn

starches exhibited similar trends under the two retrogradation

conditions studied (Fig. 3). When stored at a constant 4 C, starch of

low concentration showed lower conclusion temperatures (Tc) than

those of high concentration. After storage at 4 C for 14 days, the Tc

values were 59.6 C and 70.6 C for 20% and 50% waxy corn starch,

respectively, and those for 20% and 50% normal corn starch were

59.5 C and 69.6 C, respectively. The Tc values of both starches at

various concentrations are significantly (p < 0.05) different.

Compared to Tc, the onset temperatures for melting (To) exhibited

smaller changes with concentration. Only To values of 20% and 50%

starches are shown in Fig. 3. The To values were 33.4 C and 31.1 C

for 20% and 50% waxy corn starch, respectively, and 34.3 C and

31.5 C for 20% and 50% normal corn starch, respectively, after

storage at 4 C for 14 days. Consequently, the melting temperature

ranges (Tr) were 26.2 C and 39.5 C for 20% and 50% waxy corn

starch, and 25.2 C and 38.1 C for 20% and 50% normal corn starch,

respectively, after storage at 4 C for 14 days (Fig. 4).

Starch at lower concentration exhibited smaller Tr and lower Tc,

indicating that the crystallites formed at lower starch concentration

were more homogeneous, but less stable to thermal treatment. The

Tc values of both waxy and normal corn starches were little affected

(no difference at p < 0.05) by storage time, whereas the To

increased: from 28.3 to 33.2 C (p < 0.05) in 40% waxy corn starch

and from 26.1 to 32.6 C (p < 0.05) in 40% normal corn starch during

14 days storage at 4 C.

When both waxy and normal corn starches were stored under

the 4/30 C temperature cycling, To values were higher by 18–19 C

compared with To values at constant 4 C, regardless of the starch

concentration studied. Silverio et al. (2000) reported that To was

only controlled by propagation temperature, regardless of the type

of the starch. Storage at 30 C during the propagation step might

melt some unstable crystallites formed at 4 C, which accounted for

the To increase under 4/30 C temperature cycles (Baik et al., 1997;

Durrani and Donald, 1995; Elfstrand et al., 2004; Park et al., 2009;

Silverio et al., 2000). The remaining crystallites could be melted at

higher temperatures. Tc values of both waxy and normal starches at

20% and 30% concentration increased by about 4 C and 2 C after 14

days, respectively, whereas those at 40% and 50% concentration

were relatively unchanged compared with the Tc values at constant

4 C. The greater To but relatively similar Tc under temperature cycled

storage compared to those stored at 4 C resulted in much smaller Tr

values. The crystallites formed under the 4/30 C temperature cycled

storage were more uniform and heat stable than those formed at

a constant 4 C. The stability of the crystallites of both waxy and

normal corn starches was more improved at lower concentration, as

indicated by a large increase in Tc. However, the crystallites of both

62

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

18

Waxy

Waxy

16

14

12

Melting Enthalpy for retrogradation (J/g)

10

8

6

4

2

0

18

Normal

Normal

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Storage Time (days)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Temperature Cycles

Fig. 5. The melting enthalpy for retrogradation (DHr) of waxy (upper) and normal (lower) corn starches at various concentrations: 20% (-), 30% (C), 40% (:) and 50% (A). Starches

were retrograded at 4 C for 14 days (left) or under the temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1 day up to 7 cycles (right). Starch of 30% concentration retrograded at 4 C

(B) was included for comparison.

starches became more homogeneous at high concentration during

storage, as indicated by the large decrease in Tr.

3.4. Melting enthalpy for retrogradation (DHr)

The DHr of waxy corn starch stored at a constant 4 C was

strongly influenced by starch concentration, and maximum retrogradation occurred at 50% starch concentration, whereas that of

normal corn starch was less affected by the studied starch

concentrations (Fig. 5, no significant difference at p < 0.05).

When stored under 4/30 C temperature cycles, the DHr values of

waxy and normal corn starches were relatively smaller compared

to those of starches stored at constant 4 C (Fig. 5). Again, the

propagation temperature might have melted some unstable crystallites formed at 4 C, accounting for the decrease in DHr under 4/

30 C temperature cycles (Baik et al., 1997; Durrani and Donald,

1995; Elfstrand et al., 2004; Silverio et al., 2000). This could also be

regarded as the annealing affect in which more stable crystallites

were developed under the propagation temperature, as indicated

by the higher To, at the expense of the less stable crystallites

(Durrani and Donald, 1995; Shi and Seib, 1995; Silverio et al., 2000).

The reduction in DHr became more pronounced when the starch

concentration was low (Fig. 5). After 14 days’ storage, the DHr of 20%

waxy corn starch was 10.1 J/g when stored at the constant 4 C, but

3.5 J/g when stored under 4/30 C temperature cycles. The DHr of

50% waxy corn starch was 16.3 J/g with a constant 4 C storage and

14.5 J/g with cycled temperature storage (p < 0.05). The DHr values

of 20% and 50% normal corn starches dropped from 9.0 J/g to 6.4 J/g

(p < 0.05) and from 9.4 J/g to 9.0 J/g (no significant difference at

p < 0.05), respectively, by storing starch under the cycled temperature rather than constant 4 C. As discussed previously, the crystallites formed at a lower starch concentration under 4 C were

more homogeneous but less stable. The stable crystallites formed at

lower concentration of starch after storage at 4 C could be due to

the melting of more unstable crystallites during the subsequent

storage at 30 C. This melting resulted in a significant decrease in

DHr, whereas the crystallites were further perfected under a propagation temperature of 30 C, as indicated by the higher To and Tc.

The crystallites formed in low concentrations revealed a greater

degree of annealing under 4/30 C temperature cycles. These results

were consistent with those reported by Ward et al. (1994), who

found that 25% amylopectin showed smaller DHr but higher To than

40% amylopectin when both were nucleated at 1 C and then

propagated at 23 C.

3.5. Degree of retrogradation (DR)

Degree of retrogradation (DR) is often expressed as the ratio of

DHr to DHg (Baik et al., 1997; Jane et al., 1999; Vandeputte et al.,

2003; Varavinit et al., 2003; Ward et al., 1994). When starch

gelatinized at a concentration greater than 30% was retrograded at

constant 4 C, DR of normal corn starch was lower than that of waxy

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

100

100

20%

Degree of Retrogradation (DR)

90

80

70

70

60

60

50

50

40

40

30

30

20

20

10

10

0

30%

90

80

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

100

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

100

40%

90

50%

90

80

80

70

70

60

60

50

50

40

40

30

30

20

20

10

10

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

2

4

Storage Time (days)

6

8

10

12

14

Storage Time (days)

100

100

20%

90

Degree of Retrogradation (DR)

63

30%

90

80

80

70

70

60

60

50

50

40

40

30

30

20

20

10

10

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1

7

100

2

3

4

5

6

7

100

40%

90

80

80

70

70

60

60

50

50

40

40

30

30

20

20

10

10

0

50%

90

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Temperature Cycles

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Temperature Cycles

Fig. 6. The degree of retrogradation (DR) for waxy (blank) and normal (filled) corn starches at various concentrations. Starches were retrograded at 4 C for 14 days (upper) or under

the temperature cycles of 4 C for 1 day and 30 C for 1 day up to 7 cycles (lower).

corn starch, whereas DR of normal corn starch at 20% concentration

was higher than that of waxy corn starch (Fig. 6). These results were

roughly in agreement with those reported by Liu and Thompson

(1998). They claimed that the lower retrogradation enthalpy of 50%

normal corn starch was due to a smaller proportion of amylopectin

in normal corn starch than in waxy corn starch, since retrogradation of starch occurring below 100 C is primarily due to the

amylopectin (Fredriksson et al., 1998). This theory does not explain

why normal corn starch at 20% concentration retrograded to

a larger extent than its waxy corn starch counterpart. It is more

likely that at lower concentrations, amylose partially contributes to

the amylopectin crystalline formation in normal corn starch.

Similar to the case of the isothermal storage, normal corn

starches of high concentration (i.e. >30%) exhibited lower DR than

that of waxy corn starches when stored under 4/30 C temperature

cycles (Fig. 6), and showed high DR when starch content was 20% or

30%. Furthermore, the retrogradation endotherm was too small to

be calculated for 20% waxy corn starch after the first 4/30 C

64

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

temperature cycle, whereas a relatively large retrogradation

endotherm was observed for 20% normal corn starch stored under

the same condition (Fig. 2B). Similar results were reported by Shi

and Seib (1995). They observed no retrogradation endotherm in

waxy corn starch or waxy rice starch at 25% concentration after

storage at 4 C for 1 day followed by storage at 23 C for 4 weeks. On

the other hand, normal wheat and corn starches at 25% concentration showed significant retrogradation under the same storage

conditions. These differences in starch retrogradation between

waxy and normal starches occurred because the rate of nucleation

at 4 C was slow for waxy starch at 25% concentration compared to

those starches containing amylose. The amylose molecules in the

normal corn starch at low concentration probably promoted the

retrogradation of amylopectin molecules of gelatinized normal

starch during storage.

To date, the exact influence of amylose on starch retrogradation

remains unclear (Vandeputte et al., 2003). Russell (1987a) studied

the retrogradation properties of high amylose corn, waxy corn,

potato and wheat starches at 43% concentration and reported that

a degree of cooperation appears to exist between amylose and

amylopectin. Gudmundsson and Eliasson (1990) showed that

synergistic interactions between amylose and amylopectin

occurred during retrogradation when the starch had very high

amylose content (75–90%), and the total starch concentration was

about 50%. They deduced that at low amylopectin content the

amylose component functions as nuclei and/or co-crystallizes with

the amylopectin to some degree. Fredriksson et al. (1998) also

found that high amylose barley starch retrograded to a higher

extent than waxy and normal barley starches when the starch

concentration was about 50%. At a starch concentration of 50%,

amylose may promote crystallization of amylopectin, especially

when amylose is present in a greater amount than amylopectin. In

our study, normal corn starch retrograded to a larger extent than

waxy corn starch especially at the early storage period, either at

constant 4 C or under 4/30 C temperature cycles when the starch

content was low (20% or 30%), and 20% waxy corn starch gave no

DH after 1 cycle. The amylose in normal corn starch may have

synergistic interactions with amylopectin for recrystallization at

low starch concentration.

It is well known that starch retrogradation occurs as two

kinetically distinct processes: rapid gelation of amylose via

formation of a double helical chain segment followed by helix–

helix aggregation; and slow recrystallization of the short amylopectin chains (Baik et al., 1997; Miles et al., 1985; Ring et al., 1987).

When waxy corn starch of a low concentration (i.e., less than 30%) is

gelatinized, the amylopectin clusters are relatively far apart,

making it difficult for them to re-associate. Amylose molecules in

normal corn starch of low concentration could freely leach out

during gelatinization, and gelate quickly (Ratnayake and Jackson,

2007). Some double helical chains of gelated amylose molecules

might act as nuclei, which facilitate recrystallization of amylopectin

molecules. It is also possible that the gelation of amylose could

make less water available for amylopectin molecules, thus causing

the amylopectin clusters to combine. As a result, DR of normal corn

starch stored at the constant 4 C could be higher than that of waxy

corn starch counterpart in this study. When starch was subjected to

4/30 C temperature cycling treatment, storage at 4 C for 1 day was

too short for waxy corn starch of 20% concentration to form

extensive nucleation, and the crystallites formed were relatively

weak. On subsequent storage at 30 C, those unstable crystallites

could be melted. On the other hand, amylose in 20% normal corn

starch might function as nuclei and also co-crystallize with

amylopectin at 4 C. The formed crystallites might readily proceed

a subsequent propagation during the storage at 30 C. At a higher

concentration, because of the heterogeneity in the water

distribution during starch gelatinization, some of the clusters were

close to each other after gelatinization and easily recrystallized, due

to the reduced mobility of amylopectin molecules. This might

reduce the amount of leached out amylose, subsequently lowering

its synergistic effect on retrogradation of amylopectin molecules.

It was also observed that after three temperature cycles, DR of

waxy corn starch at 30% concentration exceeded that of normal

corn starch. Retrogradation of amylopectin occurred faster in

normal than in waxy corn starch at the early stage of storage due to

the partial contribution of amylose to the amylopectin retrogradation in normal corn starch. Retrogradation of amylopectin leveled off in normal corn starch after three temperature cycles,

whereas it continued in waxy corn starch resulting in greater DR,

because of higher proportion of amylopectin in waxy than normal

corn starch.

4. Conclusion

Retrogradation characteristics of corn starch gels can be modified by using temperature cycling. The degree of recrystallization

was less under 4/30 C temperature cycling compared to isothermal

4 C storage, based on DH of the DSC endotherm. The crystallites

formed, however, appeared more homogeneous with higher

thermal stability by temperature cycling. Under temperature

cycling, annealing of starch was greater when the starch content

was low (20% vs. 50%), implying the significance of chain mobility.

Level of retrogradation was greater in normal corn starch than in

waxy corn starch at a low concentration (20 or 30%), indicating that

the amylose might have synergistic interactions with amylopectin

for recrystallization. Overall data show that the temperature

cycling induces different retrogradation behavior compared to

typical isothermal storage, and is applicable to control retrogradation properties of starchy foods.

References

Baik, M.Y., Kim, K.J., Cheon, K.C., Ha, Y.C., Kim, W.S., 1997. Recrystallization kinetics

and glass transition of rice starch gel system. Journal of Agricultural and Food

Chemistry 45, 4242–4248.

Bemiller, J.N., 2007. Carbohydrate Chemistry for Food Scientists, second ed. AACC

International.

Biliaderis, C.G., 1992. Structures and phase-transitions of starch in food systems.

Food Technology 46, 98–109.

Biliaderis, C.G., Page, C.M., Maurice, T.J., Juliano, B.O., 1986. Thermal characterization

of rice starches: a polymeric approach to phase-transitions of granular starch.

Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 34, 6–14.

Donovan, J.W., 1979. Phase-transitions of the starch–water system. Biopolymers 18,

263–275.

Durrani, C.M., Donald, A.M., 1995. Physical characterization of amylopectin gels.

Polymer Gels and Networks 3, 1–27.

Eerlingen, R.C., Crombez, M., Delcour, J.A., 1993. Enzyme-resistant starch. I. Quantitative and qualitative influence of incubation time and temperature of autoclaved starch on resistant starch formation. Cereal Chemistry 70, 339–344.

Elfstrand, L., Frigard, T., Andersson, R., Eliasson, A.C., Jonsson, M., Reslow, M.,

Wahlgren, M., 2004. Recrystallisation behavior of native and processed waxy

maize starch in relation to the molecular characteristics. Carbohydrate Polymers 57, 389–400.

Evans, I.D., Haisman, D.R., 1982. The effect of solutes on the gelatinization

temperature-range of potato starch. Starch-Stärke 34, 224–231.

Fredriksson, H., Silverio, J., Andersson, R., Eliasson, A.C., Aman, P., 1998. The influence of amylose and amylopectin characteristics on gelatinization and retrogradation properties of different starches. Carbohydrate Polymers 35, 119–134.

Garcia, V., Colonna, P., Bouchet, B., Gallant, D.J., 1997. Structural changes of cassava

starch granules after heating at intermediate water contents. Starch-Stärke 49,

171–179.

Gudmundsson, M., Eliasson, A.C., 1990. Retrogradation of amylopectin and the

effects of amylose and added surfactants emulsifiers. Carbohydrate Polymers

13, 295–315.

Jane, J., Chen, Y.Y., Lee, L.F., McPherson, A.E., Wong, K.S., Radosavljevic, M.,

Kasemsuwan, T., 1999. Effects of amylopectin branch chain length and amylose

content on the gelatinization and pasting properties of starch. Cereal Chemistry

76, 629–637.

X. Zhou et al. / Journal of Cereal Science 51 (2010) 57–65

Jang, J.K., Pyun, Y.R., 1996. Effect of moisture content on the melting of wheat starch.

Starch-Stärke 48, 48–51.

Jang, J.K., Pyun, Y.R., 1997. Effect of moisture level on the crystallinity of wheat

starch aged at different temperatures. Starch-Stärke 49, 272–277.

Klucinec, J.D., Thompson, D.B., 1999. Amylose and amylopectin interact in retrogradation of dispersed high-amylose starches. Cereal Chemistry 76, 282–291.

Lai, V.M.F., Lu, S., Lii, C., 2000. Molecular characteristics influencing retrogradation

kinetics of rice amylopectins. Cereal Chemistry 77, 272–278.

Liu, H.S., Yu, L., Chen, L., Li, L., 2007. Retrogradation of corn starch after thermal

treatment at different temperatures. Carbohydrate Polymers 69, 756–762.

Liu, H.S., Yu, L., Xie, F.W., Chen, L., 2006. Gelatinization of cornstarch with different

amylose/amylopectin content. Carbohydrate Polymers 65, 357–363.

Liu, Q., Thompson, D.B., 1998. Effects of moisture content and different gelatinization heating temperatures on retrogradation of waxy-type maize starches.

Carbohydrate Research 314, 221–235.

Longton, J., Legrys, G.A., 1981. Differential scanning calorimetry studies on the

crystallinity of aging wheat-starch gels. Starch-Stärke 33, 410–414.

Miles, M.J., Morris, V.J., Orford, P.D., Ring, S.G., 1985. The roles of amylose and

amylopectin in the gelation and retrogradation of starch. Carbohydrate

Research 135, 271–281.

Park, E.Y., Baik, B.-K., Lim, S.-T., 2009. Influences of temperature-cycled storage on

retrogradation and in vitro digestibility of waxy maize starch gel. Journal of

Cereal Science 50, 43–48.

Ratnayake, W.S., Jackson, D.S., 2007. A new insight into the gelatinization process of

native starches. Carbohydrate Polymers 67, 511–529.

Ring, S.G., Colonna, P., Ianson, K.J., Kalichevsky, M.T., Miles, M.J., Morris, V.J.,

Orford, P.D., 1987. The gelation and crystallization of amylopectin. Carbohydrate

Research 162, 277–293.

65

Russell, P.L., 1987a. The aging of gels from starches of different amylose amylopectin

content studied by differential scanning calorimetry. Journal of Cereal Science 6,

147–158.

Russell, P.L., 1987b. Gelatinization of starches of different amylose amylopectin

content: a study by differential scanning calorimetry. Journal of Cereal Science

6, 133–145.

Sasaki, T., Yasui, T., Matsuki, J., 2000. Effect of amylose content on gelatinization,

retrogradation, and pasting properties of starches from waxy and nonwaxy

wheat and their F1 seeds. Cereal Chemistry 77, 58–63.

Shi, Y.C., Seib, P.A., 1995. Fine-structure of maize starches from four wx-containing

genotypes of the W64A inbred line in relation to gelatinization and retrogradation. Carbohydrate Polymers 26, 141–147.

Silverio, J., Fredriksson, H., Andersson, R., Eliasson, A.C., Aman, P., 2000. The effect of

temperature cycling on the amylopectin retrogradation of starches with different

amylopectin unit-chain length distribution. Carbohydrate Polymers 42, 175–184.

Slade, L., Oltzik, R., Altomare, R.E., Medcalf, D.G., 1987. Accelerated staling of starch

based products. United States Patent. 4657770.

Vandeputte, G.E., Vermeylen, R., Geeroms, J., Delcour, J.A., 2003. Rice starches. III.

Structural aspects provide insight in amylopectin retrogradation properties and

gel texture. Journal of Cereal Science 38, 61–68.

Varavinit, S., Shobsngob, S., Varanyanond, W., Chinachoti, P., Naivikul, O., 2003.

Effect of amylose content on gelatinization, retrogradation and pasting properties of flours from different cultivars of Thai rice. Starch-Stärke 55, 410–415.

Ward, K.E.J., Hoseney, R.C., Seib, P.A., 1994. Retrogradation of amylopectin from

maize and wheat starches. Cereal Chemistry 71, 150–155.

Yuan, R.C., Thompson, D.B., Boyer, C.D., 1993. Fine-structure of amylopectin in

relation to gelatinization and retrogradation behavior of maize starches from 3

wx-containing genotypes in 2 inbred lines. Cereal Chemistry 70, 81–89.