The Bolognese Academy, Carracci Family and

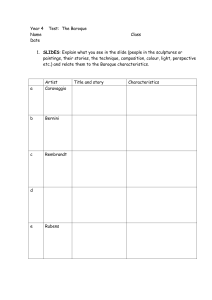

advertisement

The Bolognese Academy, Carracci Family, and Illusionism Maria Korol Sara Rasoulian Scott Stormer Sumbla Yasdanie Historical Context Counter Reformation • Challenging the Protestant Reformation • Treaty of Westphalia, 1648 • Promotion and restoration of Latin Catholicism Bridging the gap between the imperfect world and the world beyond • Lifting the barrier • Blending angles into our imperfect world Served the interest of court society and the church The Bolognese Academy • Established by the Carracci family members – Agostino (1557-1602) and Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) – Ludovico Carracci (15551619) Founded on the premise that art can be taught - primacy of studio training • Promoted the traditions of the Renaissance and the Classical model • Advanced the study of anatomy and life drawing • Primary movement in Baroque art • • Upper left: Annibale Carracci, detail of Loves of the Gods ceiling fresco at he Palazzo Farnese Gallery, Rome, Italy. Below it: Annibale Carracci, Assumption of the Virgin Mary, 1600-01,Oil on canvas, 245 x 155 cm Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome PIETRO DA CORTONA, Triumph of the Barberini, Ceiling Fresco in the Gran Salone, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, Italy, 1633-1639 PIETRO DA CORTONA, Triumph of the Barberini (Divine Providence), 1633-1639 • Commissioned by Pope Urban VIII for the Grand Salon of the Palazzo Barberini in Rome • Central composition exhibits flying maidens holding aloft the papal keys, tiara, with robe belt above a swarm of heraldic giant golden bees • the “Barberini Bees” represent teamwork and industriousness, two well-known Barberini characteristics • The most important decorative commission of the 1630s. Characteristics: • Heroic • Christian undertones • Symbolism • Illusionistic Cultural Influences • Venice and Northern Italy from 1600-1800 remained a flourishing artistic center, even as its political and economic status declined over the course of two centuries. Venice was a cultural capital of Europe, and the Academy in Bologna founded by the Carracci family trained artists in a classical tradition. Foreign artists were attracted to Northern Italy because of the aristocratic families commissioning art works. The Bolognese Academy became the center for progressive art at the time, Naturalism infused with Classicism ushered in the Baroque style, and the reform efforts by the Carracci family influenced a generation of artists in Italy. • The concern with truth and nature became a big part of the culture in Italy. The Bolognese school developed around the Carracci family attempted to get rid of mannerism by returning to High Renaissance principles of clarity and balance. The school most likely started as a casual gathering of young artists with similar ideas, wanting to reform art. The Carracci family turned to Correggio, Titian, and Veronese for inspiration and used there styles into their own works. Around 1580 the Carracci family opened the Bolognese School. The new style of simple, clear, direct pictures, portraying the truth of the subject fit the demands of the Counter-Reformation which advocated that there be no barriers for the observer and object in religious art. The Counter- Reformation advocated the truth to common experiences and inspires human faith. The academy emphasized drawing from life, and connecting truth to nature. Gestures and expression of figures for the art works encouraged the viewer to become an active participant in the piece. The excessive amount of Mannerist painters at the time led to the Carracci family to take it upon themselves to reform art through research and experiment. The Carracci family reformed the style of painting by referencing it to the Roman models of Renaissance art. The success of the academy led Annibale to receive an invitation to decorate the ceiling of the Palazzo, and soon the movement became the most influential force in Italian Baroque painting. Cultural Influences continued • Baroque art returned to Renaissance principles, and addressed the senses, emotions, and intellect of the viewer. Caravaggio was already in Rome before Annibale. Caravaggio was the first artist to really grasp the full illusionistic potential of Bolognese techniques, and his style was associated as a product of the naturalistic conventions. • Annibale’s work represented what might be and what should be. Caravaggio’s work represented more of what is the truth in direct observation. However, Annibale was heavily influenced by Caravaggio’s work, and Caravaggio became the leader behind an entire school of Baroque Naturalists (secondary movement). • The new reform efforts influenced a new generations of artists and art work. Artists like Reni, Domenichino, Albani, and Lanfranco were all trained by the Carracci at their academy in Bologna. In 1625, Lanfranco painted the dome of the church of Saint’ Andrea della Valle in Rome with his “Assumption of the virgin”, The painting was inspired by Correggio’s Renaissance ceiling in Parma. The illusionistic effects helped make the painting one of the first high baroque masterpieces. Lanfranco’s work in Rome and Naples became critical to the development of illusionism in Italy, and Domenichino went on to become Rome’s leading painters. • The accomplishment of the Carracci Family included achieving a revitalization of traditions of Italian Renaissance painting. These new principles of reform influenced the course for painting in Italy and France in the 17th century, but with greater clarity of purpose and intellectual force. ANTONIO DA CORREGGIO, Assumption of the Virgin, 1526-1530, Fresco 1093 x 1195 cm Cathedral of Parma ANTONIO DA CORREGGIO, Assumption of the Virgin 1526-1530, fresco, Cathedral of Parma “Assumption of the Virgin” by Correggio portrays the assumption of Mary into heaven. The painting was done in plaster with water-soluble pigments which served as the inspiration for the baroque style of dramatic illusionistic ceiling painting. Correggio used the sotto in su perspective, which means seen from below in Italian. The technique creates an illusion that the figures are floating in space above the viewer, which was common in Baroque fresco cycles. Correggio was one of the most important northern Italian painters, and the Parma ceiling is one of his best know pieces. Correggio was influenced by Andrew Mantegna, with his invention of foreshortening. The new technique allowed the viewer to be pulled back into the art piece. He was also influenced by classical works of Leonardo, Raphael, and the Venetians, and he was inspired by the intense coloring of the local Bolognese school. The illusionistic effects with steeply foreshortening figures floating above the viewer inspired numerous Baroque artists including Annibale Carracci who was Correggio’s greatest predecessors (his influence can be seen in Carracci’s Farnese ceiling). The painting shows a view of the sky with rings of clouds where hundreds of figures performed a dance in celebration of the Assumption. His use of illusionism enhances the dramatic effect of the piece. Subject and Style of the Bolognese Academy • • • • • • The Carracci brothers Agostino and Annibale, and their cousin Ludovico formed the Academy of the Progressives (Bolognese Academy) at the beginning of 1580 in response to the Mannerist style, which they regarded as false and artificial. They rejected the Mannerist use of previous artworks as models, and promoted the direct observation of nature. They emphasized the importance of drawing, and the use of preliminary sketches. The main subject for their works was Classic mythology with Christian undertones. The Bolognese Academy style was influenced by that of High Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael. Top left: CARRACCI, Annibale, Self-Portrait in Profile, 1590s, Oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence Below it: CARRACCI, Annibale,The Flight into Egypt, 1603, Oil on canvas, 122 x 230 cm, Galleria Doria-Pamphili, Rome Palazzo Farnese, Rome, Italy • Annibale Carracci was commissioned to paint frescoes in the palace of Cardinal Odoardo Farnese in 1595. • Annibale first painted the Camerino (small room) with the stories of Hercules. • In 1597 he started his masterpiece “Loves of the Gods” in the larger gallery of the Farnese palace. Image on the right: Annibale Carracci, Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne, central panel of Loves of the Gods, 1597-1602, Rome, Italy, 1597-1601 • • The Loves of the Gods gallery in the Palazzo Farnese represents a great collection of classical paintings, with illusionistic elements such as the painted frames and painted sculpture. It shows the influence of High Renaissance works such as the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling fresco by Michelangelo, and the frescoes in the Vatican Loggie by Raphael. The “Toolbox” of Illusionism • Perspective: A method of presenting an illusion of the three dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. (developed by Brunelleschi in the Early Renaissance) • Foreshortening: the use of perspective to represent the apparent visual contraction of an object that extends back in space at an angle to the perpendicular plane of sight. (developed by Mantegna in the Early Renaissance) • Trompe L’Oeil: French, “fools the eye.” A form of illusionistic painting that aims to deceive viewers into believing that they are seeing real objects rather than a representation of those objects. • Painters such as Pietro da Cortona, Giovanni Battista Gaulli, and Fra Andrea Pozzo would further investigate and develop Illusionism in the form of ceiling frescoes, mostly produced for Catholic churches, during the Baroque period. Italian Baroque ceiling frescoes: Materials and Processes • The first part of the overall plan of a ceiling fresco started with an extensive amount of preliminary drawings, many of which used red chalk. The Caracci academy was well known for it’s use of life studies, and for Annibale’s commitment to the study of nature. So the first parts in the process of monumental ceiling frescoes in the High Baroque era consisted of the design phases and studies from life for the majority of the figures in the compositions. • Top left: a life study, a seated ignudo looking upward, 15981599, black chalk heightened with white on gray-blue paper, laid down 495 x 384 (19 1/2 x 15 1/8), Musee du Louvre, Paris. Below it: , a drawing in sinopia pigment, Annibale Carraci, attributed, St. Sebastian. Red chalk on heavy cream laid paper, c. 1606. • • • • • Many of these survive, although there obviously must have been many more. Annibale would also use this phase of the process to design the overall composition through his drawings before proceeding onto the larger cartoons. This leads to the next phase of the process, again another preliminary stage before actually being involved in the painting of the ceiling. The next part of this process, after the initial life studies and planning of the overall design, consisted of the execution of large-scale cartoons which would be used by the artist to quickly transfer the drawings to the plaster surface of the ceiling. Also, it is interesting to note that even though these large-scale cartoons seemed to provide for direct copying by the artist, there was some amount of freedom that the artist had in improvising with his figures as he saw fit to suit the overall composition within the actual setting of the ceiling. Before the actual painting process could take place, artists would begin by transferring their cartoons to the plastered surface by sketching them in on this surface in a red pigment called sinopia. This was responsible for later giving this first layer it’s name of sinopia, due to artist’s primarily using this pigment for their initial underdrawings. This first layer, divided into sections, was also called the arriccio. On top of this, the next layer of plaster was placed, called the intonaco, and this became the top and final surface in which the artists would directly paint on. But before the cartoons could be transferred directly to the ceiling, it had to be plastered first which leads to a discussion of the first steps in the actual process of fresco. • Fresco painting is generally divided into two types, buon fresco and fresco secco. Buon fresco consists of painting directly on wet plaster or mortar also called intonaco, with pigment mixed with water. In this process, a binder is not needed as the pigment mixed with water is enough to hold the pigment to the wall. This is in contrast, to fresco secco, which is done on dry plaster. • The majority of Italian Baroque ceiling frescoes were done using the process of buon fresco, which requires the artist to plan very carefully how much work he will be able to get done in a day due to the drying nature of the plaster. The artist would plan this by having a section of the wall plastered in the buon manner, and this area was called the gionarata which is translated to mean a day’s work. This was the area that the artist planned on finishing in the course of a day’s work and this would give the artist between 10 and 12 hours before the plaster dried. • Once this area dried, the artist could no longer paint on this area without first removing the plaster and starting over. This is one reason why some areas that needed to be redone due to mistakes or other reasons were generally re-painted using fresco secco, which allowed the artist to work on dry plaster although there were limitations with this process as well. • A typical fresco would consist of between 10 and 20 gionarata and over the course of many centuries the divisions between these gionarata can sometimes be seen from the ground although it was common for artists to paint these areas a secco and due to the fragile nature of a secco painting these sections have sense fallen off. • Fresco secco also had other limitations making it a medium that was not as commonly used as buon fresco, one of these being the limitation on colors that could be used. This meant that only stable pigments could be used, and other less stable pigments could not be used in the fresco secco process. • One of the most common pigments used in a secco was a color called azurite blue and artists sometimes used a secco painting specifically to allow for a broader range of colors that was allowed through the use of fresco secco. The combination of mainly fresco buono for the vast majority of the ceiling combined with parts of fresco secco for corrections and concealing the divisions between individual gioranta was the main process in completing a ceiling fresco. Bottom Left: Detail from a fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepelo. Left: a view of an Italian High Baroque ceiling. Bottom Right: Giovanni Battista Gaulli, adoration the name of Jesus. 1674-9. Fresco, Rome, Gesu, ceiling of the nave. FRA ANDREA POZZO, Glorification of Saint Ignatius, ceiling fresco in the nave of Sait’Ignazio, Rome Italy, 1691-1694 FRA ANDREA POZZO Glorification of Saint Ignatius, ceiling fresco in the nave of Sait’Ignazio, Rome 1691-1694 • An analysis of this work can start by exploring the first impressions of the viewer as opposed to an immediate detailed analysis of all of it’s parts. This is a good way to start, because of the fact that this ceiling, like so many other High and Late Baroque ceiling frescoes, is so grand and large in it’s composition and overall complexity, that the most important aspect of it is the initial response that it evokes. • This is a good example of something being more than just the sum of its parts, although these individual aspects of the work are important when taken together due to the fact that it is these that together make the work something exceptionally large and grand. • The subject of this fresco is an allegory of the missionary work of the Jesuits and there are personifications of the continents of Europe, Africa, Asia, and America. To start with, this Baroque ceiling is exceptional in it’s complexity, typically ornamental in true Baroque fashion, although in it’s own unique way. The use of perspective in the Pozzo ceiling • The degree of illusionism that is achieved in the Pozzo ceiling is very impressive, and this reflects his very deep understanding of the systems of perspective that were first developed by Brunelleschi and later refined and applied to painters by Alberti. • Although, the application of these systems of perspective is very different and much more sophisticated and refined in terms of the illusionistic qualities that can be obtained from it, then in works of earlier Renaissance masters. This higher degree of illusionism is a hallmark and key attribute of High and Late Baroque ceiling frescoes. • Although it is obvious that the use of perspective is based on the linear formulas of Brunelleschi and Alberti. There is a high degree of spatial depth that is contained within this ceiling with all diagonals converging towards a central point, typical of true linear perspective. The spatial depth of the picture moves towards the center from all sides with the corners being represented as being closest to the viewer with distances being represented as further away as space is represented moving away from the corners and towards the center of the composition. • The farthest implied distance is directly in the center of the picture drawing the viewer’s attention to this point. All architectural elements and figures point towards this central area which further enhances the illusion of the perspective system used in this ceiling. There is also a use of aerial perspective with figures becoming less clearly defined as the implied distances become greater. The Illusionistic Qualities The Influence of Michelangelo (Renaissance) on the Pozzo (Baroque) Ceiling • The degree of illusionism in the Pozzo ceiling is remarkable and is made apparent by studying the side figures and their relationships with the actual windows of the church directly below the ceiling. From this one can gain a sense of the incredible illusionism that was achieved in this fresco, for one cannot tell at all where the actual architecture ends and the ceiling begins. • It is interesting to look at some of the individual figure groups in this ceiling in more detail sense it is these individual groups that interact to make up the whole of the composition, along with the architectural elements. The individual figures share a lot in common with earlier Renaissance models, particularly those of Michelangelo. Pozzo’s palette is also similar in ways to this Renaissance master, showing a clarity and vividness of color, lacking sharp contrasts that are sometimes typical of the Baroque, and instead reflecting this Renaissance influence. The expressive poses and gestures of the individual figures also reflect these earlier Renaissance influences, and Pozzo may or may not have quoted directly from Michelangelo’s famous figures in his Sistine frescoes. The handling of drapery is also very similar to that of Michelangelo’s with drapery being handled in large simplified folds focusing on a unity of color with delicate highlights. Although there are also some areas with very expressive flying drapery that is very much a Baroque and not a Renaissance attribute. Top right: Detail of the prophet Jonah from Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling. Bottom left: Example of the illusionism that was achieved in the Pozzo ceiling fresco. To summarize some of the key features of the Pozzo ceiling, it may be noted that this particular Baroque fresco is unique in it’s balance of classical and baroque elements with the expression and extravagance of the figure groups balanced and contained within the classical arches and columns. Also, the spacing of the figure groups, and the amount of open space that is left within the composition serves to balance the baroque aspects with these classical ones. This balancing makes this particular Baroque fresco a truly amazing example of High Baroque illusionism. Sources • Janson, H. W., and Janson, Anthony. History of Art. Harry N. Abrams Incorporated, sixth Ed. New York, 2001. • Kleiner, Fred S. and Mamiya, Christian J. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, Western Perspective, Volume II. Thomson Wadsworth, U.S., 2006. • Web Gallery of Art. http://www.wga.hu/framese.html?/html/c/correggi/frescoes/duomo.html 06 May, 2007. • Web Museum, Paris. Carracci. http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/carracci/ • In addition, many general information sites on the artists and their works of Baroque Illusionism can be found on the World Wide Web