SELF-MANAGEMENT: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF DIFFERENT

TYPES OF REINFORCEMENT

A Thesis Presented to the Faculty

of

California State University, Stanislaus

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

of Master of Arts in Psychology

By

Rafał S. Gebauer

July 2015

CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL

SELF-MANAGEMENT: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF DIFFERENT

TYPES OF REINFORCEMENT

by

Rafał S. Gebauer

Signed Certification of Approval Page is

on file with the University Library

Dr. William Potter

Professor of Psychology

Date

Dr. Bruce Hesse

Professor of Psychology

Date

Dr. AnaMarie Guichard

Associate Professor of Psychology

Date

© 2015

Rafał S. Gebauer

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

List of Tables ..........................................................................................................

v

List of Figures .........................................................................................................

vi

Abstract ...................................................................................................................

vii

Introduction .............................................................................................................

1

Self-instruction ............................................................................................

Self-recording/monitoring...........................................................................

Self-reinforcement ......................................................................................

Different types of external reinforcement ...................................................

Weigh control techniques ...........................................................................

2

2

4

5

6

Method ....................................................................................................................

8

Participants ..................................................................................................

Apparatus and Materials .............................................................................

Design .........................................................................................................

Procedure ....................................................................................................

8

8

9

9

Results .....................................................................................................................

15

Participant 1 ................................................................................................

Participant 2 ................................................................................................

Participant 3 ................................................................................................

Participant 4 ................................................................................................

15

17

19

21

Discussion ...............................................................................................................

26

References ...............................................................................................................

32

Appendices

A. Consent form ...............................................................................................

B. Social validity questionnaire ......................................................................

C. Social validity questionnaire - results .........................................................

iv

38

41

45

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE

PAGE

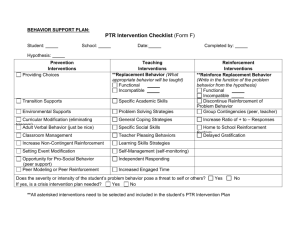

1. Intervention contingency overview...................................................................

11

2. Feedback on daily gain or loss ..........................................................................

12

3. The average number of steps or amount of water during particular conditions

24

v

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE

PAGE

1. The amount of water and number of steps for participant 1 .............................

16

2. The amount of water and number of steps for participant 2 .............................

18

3. The amount of water and number of steps for participant 3 .............................

20

4. The amount of water and number of steps for participant 4 .............................

22

vi

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to compare the effectiveness of different types of

reinforcement in self-management settings. Four university students participated in

self-management program in order to increase water intake and walking. Multiple

baseline design across behaviors which included baseline (A) condition, positive

reinforcement (B) condition, negative reinforcement (C) condition and combination

of both (B+C), was introduced. The results suggest that there is no large differences

in effectiveness of different types of reinforcement contingencies. However, the study

did show that implementing a relatively low cost reinforcement contingency did seem

to increase both target behaviors.

Key words: self-management, reinforcement, water intake, walking

vii

INTRODUCTION

The skill of controlling one’s behavior is a crucial component of an

individual’s life. The founder of radical behaviorism B.F. Skinner (1953) recognized

the importance of self-control of behavior as a method for personal development

throughout the lifespan. Later on, the term self-management was introduced, which is

now more widely in use, and is considered “a practice of techniques of self-control”

(Epstein, 1997, p. 553). After reviewing the literature it is clear that there are many

varied techniques with confusing terms, unclear definitions and/or mixed results.

Thus, the current study was a next step in order to fill in the gap in behavior analytic

knowledge by examining the functionality of reinforcement for self-management

interventions. It attempted to investigate the relative efficacy as well as provide a

comparison of different types of reinforcement (i.e. positive, negative, combination of

both).

Self-management/control is a broad area of research which includes many

approaches and techniques such as self-instructing, self-monitoring, self-recording,

self-reinforcing/ punishing to name just a few (Burgio, Whitman and Johnson, 1980;

Cihak & Gama, 2008; Duarte and Baer, 1994; Fritz, Iwata, Rolider, Camp & Neidert,

2012; Glynn, 1970; McCarl, Svobodny & Beare 1991; Newman, Buffington &

Hemmes 1996; Newman, Tuntigian, Ryan & Reinecke, 1997; Stasolla, Perilli &

Damiani, 2014).

1

2

Self-instruction

Duarte and Baer (1994) defined self-instructing as “self-talk with instructional

content”, and used this technique to improve sorting skills in preschool children.

After the children were unable to sort on their own, naming of common attributes was

introduced but this proved to be insufficient to produce accurate sorting. Thus,

researchers introduced self-instructions evoked by experimenter question “So, what

are you looking for?”. This intervention proved to be effective improving children’s

sorting skills. Burgio et al. (1980) taught self-instructing to developmentally disabled

children in order to increase their attending behavior during training and subsequently

to generalize it to one to one and classroom situation. Participants were trained to

self-instruct and after an acquisition of the skill the experimenter introduced different

types of distractors (visual, audio and in vivo) to investigate the effectiveness of the

intervention and possible generalization.

Self-recording/monitoring

Researchers have different approaches and definitions of self-monitoring and

self-recording as well as mixed data about effectiveness of these techniques. Fritz et

al. (2012) investigated components of self-management intervention such as

differential reinforcement (DR) of accurate recording or self-recording by

implementing treatment for two adults and a boy diagnosed with autism in order to

decrease their stereotypy. They attempted to assess the effectiveness of self-recording

by isolation of this technique from the other components that are often an additional

part of the intervention. The results suggested that a self-recording procedure alone is

3

ineffective or at least insufficient in the reduction of stereotypy. In other studies selfrecording proved to be an effective tool in behavior change providing highly stable

levels of target behaviors. McCarl et al. (1991) used self-recording to improve on-task

attention and academic productivity in three highly distractible girls with mild to

moderate mental handicap. The intervention, which consisted of five phases training

of self-recording, increased on-task behavior of all three participants and for two out

of three, there was an improvement in productivity. In another study Stasolla et al.

(2014) implemented self-monitoring procedure to increase on-task behavior of two

boys with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactive disorder

(ADHD). Additionally, the intervention was also aimed to decrease stereotyped

behaviors and investigate its effects on the mood. They found self-recording as an

effective tool to improve on-task behavior and increase indices of happiness and

decrease stereotyped behaviors. Taking into account inconsistent outcomes of selfrecording procedures in literature (i.e. ineffectiveness or high stable increase of target

behavior after implementation of self-recording) the current study used self-recoding

as a procedure to collect baseline data as well as enable accurate administration of

reinforcement during intervention phases. This solution was provided to ensure

minimal or easy to detect interference of self-recording technique with subject matter

of the study i.e. reinforcement. For this purpose, the self-recording/monitoring part of

the procedure was defined following Dean, Malott and Fulton’s (1983) definition,

that is self-monitoring was treated as a part of wider self-recording technique which

includes monitoring of one’s behavior and recording it afterwards.

4

Self-reinforcement

Another self-management technique that has been used by researchers is selfreinforcement or punishment (Cihak & Gama, 2008; Glynn, 1970; Newman et al.,

1996; Newman et al., 1997). Glynn (1970) compared the effects of self-determined,

experimenter-determined and chance-determined token reinforcement with no tokens.

Three conditions were assigned to four classes of grade nine girls. The selfdetermined reinforcement proved to be as effective as the experimenter-determined

one in the learning of history and geography material in the classroom. Newman et al.

(1996) successfully increased appropriate conversation in teenagers with autism. The

intervention consisted of either external or self-reinforcement where both of them

proved to be an effective procedure. Newman et al. (1997) used a self-managed

differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO) to decrease disruptive behavior

(out-of-seat or nail-flicking) in three students with autism. The intervention was

introduced using external reinforcement followed by fading realized by selfreinforcement with prompts to final unprompted self-reinforcement. This treatment

successfully decreased target behavior and allowed for the follow-up. Cihak and

Gama (2008), by using a negative self-reinforcement procedure such as noncontingent access to escape (i.e. access to a break independently of the target

behavior), were able to increase task engagement while simultaneously inappropriate

behaviors decreased. This proved to be an effective intervention for students with

moderate to severe disabilities. However, despite these somewhat successful uses of

self-reinforcement there are some significant concerns about the nature of self-

5

reinforcement as a proper term and possible procedures needed to implement it

(Catania, 1975; Goldiamond, 1976).

Different Types of External Reinforcement

The alternative to self-reinforcement in self-management interventions is

reinforcement provided by an external agent. It requires another person as an

additional component and thus increases the costs and dependence of the intervention.

It is more reliable and likely a more effective procedure since there is no reliance on

the individual’s usually poor self-control. A literature search did not find any studies

that directly targeted comparison of reinforcement methods in self-management

procedures in order to evaluate their effectiveness. Despite that, reinforcement is a

very common component of self-management studies, thus its evaluation seems to be

crucial. However, there were attempts in behavior analytic literature to investigate

different types of reinforcement (but not in a self-management context). DeLeon,

Neidert, Anders and Rodriguez-Catter (2001) compared positive and negative

reinforcement in treatment of escape maintained behaviors. They applied different

types of reinforcement in order to increase the compliance of child with autism and to

reduce her problem behaviors. The results showed that, overall, positive

reinforcement was more effective than negative. However, along with an increase in

task requirements and possible choice between reinforcements, the effects and

selection pattern became unstable (i.e., the participants chose the negative

reinforcement more often in comparison to the previous preference for positive

reinforcement). Bouxsein, Roane, and Harper (2011) investigated not only the

6

effectiveness of different types of reinforcement but also their combination. A boy

diagnosed with Down syndrome was exposed to positive or negative reinforcement or

both, contingent on compliance. In this study the data suggested that a combination of

positive and negative reinforcement was the most effective.

Weight Control Techniques

According to The World Health Organization (WHO, 2015) globally, there are

more than 1.9 billion overweight adults, 600 million of whom are obese. Hammond

and Levine (2010) report that obesity costs the United States more than 215 billion

dollars a year. Between 1980 and 2014 the number of people worldwide with a Body

Mass Index (BMI is calculated by body mass divided by the square of the body

height; the score equal to 25 or more indicates overweight) above 25 more than

doubled (WHO, 2015). This study will discuss two of the many suggestions given in

literature to change this trend.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) recommends at least

150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 minutes of vigorousintensity physical activity per week to lose weight or, a least, maintain a healthy

weight. The current study examined walking as a target behavior, in order to provide

an effective tool for weight control.

Other studies suggest that besides physical activity, drinking water regularly

throughout the day might increase weight loss and facilitate the maintenance of a

healthy weight (Muckelbauer, Sarganas, Grüneis & Müller-Nordhorn, 2013). The

current study also targeted daily water intake as a second behavior.

7

Thanks to recent technological progress researchers have begun to use a wide

variety of electronic devices (such as cellphones, Ipods Touch, mobile handheld

computers), specifically for self-recording (Bedesem & Dieker, 2014; Blood,

Johnson, Ridenour, Simmons & Crouch, 2011; Gulchak, 2008), that can provide more

control over data validity without direct observation of participants and make the

process of data collection more attractive. The current study used cell phone

applications in particular, to facilitate self-recording and increase the data validity of

walking behavior since this type of application offers automatic tracking. This study

compared the effectiveness of different types of reinforcement procedures as well as

their combination for both the targeted physical activity and water consumption.

METHOD

Participants

The participants in this study were four California State University, Stanislaus

students. Two males and two females ages 19 to 21 years old were recruited by the

experimenter based on their willingness and having the time to run a selfmanagement procedure. Before collecting the baseline data, all of the participants

reported drinking no more than two cups of water per day. All of them had access to a

smartphone as well as to an internet connection to collect self-recording data using an

application on the phone and forward it to the researcher. The participants with prior

knowledge of self-management were excluded from the study - this was assessed by

questioning them. The participants may have obtained extra credit points for

participating if available. All of them were treated according to “Ethical Principles of

Psychologists and Code of Conduct” (American Psychological Association, 2010)

and read and signed an informed consent form (see Appendix A)

Apparatus and Materials

Various smartphone type phones with access to internet were used

(participants supplied the phones – they ranged from Samsung Galaxy S3, Samsung

Galaxy S5 to LG G3). Participants were asked to download two applications Noom

Walk Pedometer: Fitness (2015) and Water Your Body (2015). Noom Walk

Pedometer: Fitness was used to collect the data about walking behavior and Water

Your Body allowed the participants to provide information in regards to amount of

8

9

water they drank. Participants were asked to summarize their achievements on a daily

basis by sending, to the researcher, e-mail messages with screen shots from their

phone showing current data for each of the behaviors. This included the total number

of steps and total amount of water intake. As a part of that message, they were also

asked to self-evaluate by saying if they met the criteria and whether or not they

should get the reinforcement or avoid a loss. A google doc data sheet was used to

provide the questionnaires on social validity in this study. (See Appendix B)

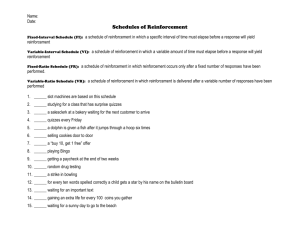

Design

The study was a multiple baseline design across behaviors which included a

baseline (A) condition, positive reinforcement (B) condition, negative reinforcement

(C) condition and combination of both (B+C). To counterbalance possible order

effects participants were exposed to a randomly selected condition order. Thus, after

the baseline there was an equal chance for any participant to begin the intervention

with any of the three possible conditions followed by others also in random order.

Because of the applied nature of the study the transition to the next condition was

provided always after 7 days with an exception for the water intake baseline which

lasted for 4 days and last condition of the same behavior which lasted for 10 days in

order to satisfy the control requirements of multiple baseline design.

Procedure

After meeting the recruitment criteria the participants had an initial 45 minute

training session with the researcher. That session provided them with an overview of

the study requirements and prepared them for the self-recording phase of the study.

10

The session included a general discussion about the purpose and nature of the study,

lessons on self-management and the techniques that were going to be implemented.

Then, participants were instructed to download the relevant applications and the

researcher taught how to use them. To assure valid data collection of water intake

behavior the researcher provided a water bottle with volume markings for each of the

participants. Specific instructions about self-recording and the method of

reinforcement for participants were provided.

The reinforcer was a total of $52 per behavior ($58 for one of them because of

three additional days in the last condition to satisfy the multiple baseline design

requirements). This amount included $14 ($20 in the last condition of one of the

behaviors) available in each of the intervention’s conditions calculated by multiplying

the number of days in a condition by $2 as well as a $10 incentive for participation

and consistent self-recording provided at the end of the study. The researcher

explained that participants would gain $2 for every day they met a criteria during a

positive reinforcement condition and no consequence would be delivered if they

failed to meet a criteria during that condition. Subsequently, in a negative

reinforcement condition $2 was subtracted from the entire amount of money available

to the participant during that phase of the study (in this case number of condition days

* $2) every time they did not meet criteria. Therefore, they could lose the chance to

get $2, and no consequence was provided upon the success in fulfilling the criteria.

Thus, if they did not meet the goal each day for the behavior being considered, they

would lose all the money within 7 (10) days of not meeting the goal. Finally, during

11

the condition with both positive and negative reinforcement, participants received $2

every time they met a criteria, but $2 was subtracted from the total, every time they

did not meet a criteria. See Table 1 for a summary of the monies available and the

contingencies involved for each condition.

Table 1

Intervention Contingency Overview

Condition

Number of

days

Positive

7 (10)

Reinforcement

Total

Monies

$14 ($20)

Negative

Reinforcement

7 (10)

$14 ($20)

Positive and

Negative

Reinforcement

7 (10)

$14 ($20)

Self-recording Participation

28

$10

Contingency Stated

Each day the goal is met,

you will earn $2 of the

$14 ($20) available.

Each day the goal is not

met, you will lose $2 from

the pool of the $14 ($20)

available.

Each day the goal is met,

you will earn $2 of the $14

($20) available and each

day the goal is not met, you

will lose $2 of the $14

($20) available.

You will get additional $10

for providing self-recording

data every day throughout

the study

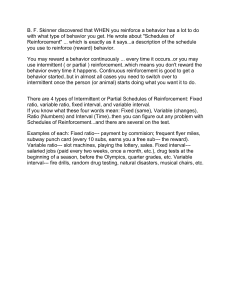

Additionally, participants were asked to share their achievements every day

via the e-mail messages and to keep track of their daily dollar gain or loss. In order to

provide immediate contact with the reinforcement contingency the researcher

provided daily feedback about participants’ achievements and currently accumulated

money for each phase (See Table 2 for a summary). After each week the researcher

12

totaled the amount of obtained reinforcement, met with participants to deliver the

money and provide information on the next actions.

Table 2

Feedback on daily gain or loss

Condition

Walking

Congratulations!

Criteria Today, you did: XX steps

was

You earned: $2

met

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Positive

Reinforcement

Sorry.

Criteria Today, you only did: XX steps

was not You earned: $0.

met

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Congratulations!

Criteria Today, you did: XX steps

was

You didn’t lose: $2

met

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Negative

Reinforcement

Sorry.

Criteria Today, you only did: XX steps

was not You lost: $2

met

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Congratulations!

Criteria Today, you did: XX steps

was

You earned: $2

met

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Positive and

Days to go in this phase: X

Negative

Sorry.

Reinforcement

Criteria Today, you only did: XX steps

was not You lost: $2

met

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Water Intake

Congratulations!

Today, you drank: XX oz.

You earned: $2

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Sorry.

Today, you only drank: XX oz.

You earned: $0.

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Congratulations!

Today, you drank: XX oz.

You didn’t lose: $2

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Sorry.

Today, you only drank: XX oz.

You lost: $2

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Congratulations!

Today, you drank: XX oz.

You earned: $2

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

Sorry.

Today, you only drank: XX oz.

You lost: $2

You’ve accumulated: $XX

Days to go in this phase: X

13

After discussion about the procedures and reinforcement the participants were

encouraged to ask questions and express any concerns. When everything was clear

they signed the informed consent. They were verbally prompted to immediately

inform the researcher about any health problems during the study and were given the

contact information for the CSU Stanislaus Student Health Center. Participants were

next assigned to a unique random order of conditions. At the end of the introductory

session, the researcher weighed participants and recorded it as their starting weight.

Finally, they were asked to start collecting daily baseline data until the researcher

contacted them with further instructions. Subsequent meetings were provided

separately for each participant based on the collected data in order to change the

condition at the appropriate time to meet the requirements of the multiple baseline

design. After the first training session, the researcher met with each participant a total

of seven times, once after each phase for each behavior (three phases with two

behaviors each) during the study and once after the study in order to summarize the

results, provide incentives, collect the data on weight and go through the debriefing

process.

The daily criteria for walking took into consideration The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (2014) recommendations about the suggested amount of

physical activity per week. However, the actual criteria were established using

baseline data to ensure an appropriate level of difficulty without unnecessary risk and

effort but to reveal potential differences between reinforcements. This was

14

accomplished by calculating the average from four days with the highest number of

steps during baseline and increasing it by 50%.

The daily water intake criteria took into consideration the WHO (2004)

recommendations. However, because of the minimal participants’ water intake prior

to the study that did not match the recommendations the criteria were determined by

increasing the average of two days with the highest water intake by 50 %.

The criteria levels for both behaviors were kept constant throughout the study.

Since the objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of different

reinforcements, the emphasis was placed on the consistency (i.e. performing the

behavior every day on the particular level). Because of that, the criteria were

relatively easy to achieve but enough of a challenge to reveal any differences among

the reinforcing contingencies during conditions.

Finally, a social validity measure was taken at the end of the study but before

debriefing to ensure objectivity (see Appendix B). It was provided to the participants

anonymously as an online survey.

15

RESULTS

The data indicated good control of the reinforcement contingency over the

behaviors. There was a significant increase from baseline, across all participants and

behaviors, when the intervention was introduced. Visual analysis suggests that there

were no differences among the different reinforcement conditions’ effectiveness.

However, in general (for 2 out of 4 participants) the data in the negative

reinforcement phase proved to be more stable in comparison to the other two: positive

reinforcement and combination of positive and negative reinforcement conditions.

None of the participants’ weight decreased during the study. For two the

weight stayed the same. For the other two, weight increased, but within the range of

normal body weight fluctuation (i.e. there are usually day to day changes in our

weight without any interference from outside), which makes this increase irrelevant

data to this research.

Participant 1 (see Figure 1)

The amount of water intake during baseline ranged between 12 and 32 oz.

There was large increase from the last data point of the initial condition (30 oz.) to the

first one of the intervention (52 oz.). In the first intervention phase (positive

reinforcement) water intake varied from 52 to 64 oz. During that phase Participant 1

met the criteria every day. In the subsequent condition (negative reinforcement) the

amount of water ranged between 51 and 64 oz. each day criteria were met. Finally, in

the last condition (combination of positive and negative reinforcement) water intake

varied between 52 and 64 oz. and again Participant 1 met the criteria every day.

16

The number of steps in baseline varied from 1751 to 4951 steps. Similar to

water intake, the data increased greatly from the last data point of the initial phase

(2527 steps) to the first one of intervention (6667 steps). In the first intervention

condition (positive reinforcement) the number of steps varied between 4553 and

6964. During that phase Participant 1 met the criteria every day but one. In the next

phase (negative reinforcement) the number of steps ranged from 6149 to 6983 and all

17

of the criteria were met. Finally in the last phase (combination of positive and

negative reinforcement) number of steps varied from 3618 to 8960 and Participant 1

met the criteria every day but one.

In Participant’s 1 walking data there are 3 data points which are significantly

different from the main data path. Participant 1 reported verbally, during last meeting,

that on day 9 and 23 scores were low and Participant 1 did only 4553 and 3618 steps

respectively because of the day off at work. However, on day 22 Participant 1 did

8960 steps, which was due to a trip to the zoo.

Participant’s 1 weight did not change. From the initial 108 lbs. it stayed as 108

lbs. as the final weight.

Participant 2 (see Figure 2)

The amount of water intake during baseline ranged between 48 and 75 oz.

There was a big increase from the last data point of the initial condition (75 oz.) to the

first one of the intervention (115 oz.). In the first intervention phase (negative

reinforcement) water intake varied from 114 to 124 oz. During that phase Participant

2 met the criteria every day. In the combination of positive and negative

reinforcement condition the amount of water intake ranged between 120 and 168 oz.

and all of the criteria were met. Finally, in the last condition (positive reinforcement)

water intake varied between 120 and 192 oz. and again the Participant 2 met the

criteria every day.

18

The number of steps in baseline varied from 2469 to 11198 steps. Similar to

water intake the data showed a large increase from the last data point of the initial

phase (5630 steps) to the first one of intervention (11313 steps). In the first

intervention condition (negative reinforcement) the number of steps varied between

19

9820 and 17327. During that phase Participant 2 did not meet the criteria three times.

In the next phase (combination of positive and negative reinforcement) the number of

steps ranged from 15480 to 17851 and all of the criteria were met. Finally in the last

phase (positive reinforcement) number of steps varied from 15091 to 28818 and

Participant 2 met the criteria every day.

In Participant’s 2 walking data there were 4 data points that were significantly

different from the main data path. Participant 2 reported verbally that on day 8, 9, and

10 scores were low and Participant 2 did only 11313, 9820 and 11215 steps

respectively because he was surprised that the criteria was so high. However, on day

28 Participant 2 did 28818 steps which was due to a busy day on campus.

Participant’s 2 weight changed. From the initial 164.2 lbs. it increased to the

170.8 lbs. for the final weight. This change is within day to day body weight

fluctuation.

Participant 3 (see Figure 3)

The amount of water drunk by this participant during baseline ranged between

16 and 40 oz. There was a big increase from the last data point of the initial condition

(40 oz.) to the first one of the intervention (61 oz.). In the first intervention phase

(negative reinforcement) water intake varied from 61 to 72 oz. During that phase

Participant 3 met the criteria every day but one. In the next condition (positive

reinforcement) the amount of water ranged between 64 and 68 oz. and each days’

criterion was met. Finally, in the last condition (combination of positive and negative

20

reinforcement) water intake varied between 60 and 72 oz. and, again, Participant 3

met the criteria every day.

21

The number of steps in baseline varied from 1649 to 4218 steps. From the last

data point of the initial phase (4218 steps) to the first one of intervention (2772 steps)

there was a jump in the direction opposite to what was expected. However, the next

data point (6324 steps) showed an increase similar to the one in water intake. In the

first intervention condition (negative reinforcement) the number of steps varied

between 2772 and 12638. During that phase Participant 3 meet the criteria every day

but one. In next phase (positive reinforcement) the number of steps ranged from 6116

to 6494 and all of the criteria were met. Finally in the last phase (combination of

positive and negative reinforcement) the number of steps varied from 1027 to 7230

and Participant 3 failed to meet the criteria on two days.

In Participant’s 3 walking data there were 3 data points which were significantly

different from the main data path. Participant 3 reported verbally that on day 22 and

26 scores were low and Participant 3 did only 2746 and 1027 steps respectively

because of the days off of work. However, on day 11 Participant 3 did 12638 steps

which was due to a trip with friends to the another city to watch a baseball game.

Participant’s 3 weight changed slightly. From the initial 189.8 lbs. it increased

to the 190.4 lbs. of the final weight. This change is within day to day body weight

fluctuation or could be even treated as a measurement error.

Participant 4 (see Figure 4)

The amount of water intake during baseline ranged between 33 and 57 oz.

There was a large increase from the last data point of the baseline condition (46 oz.)

to the first one of the intervention (82 oz.). In the first intervention phase (positive

22

reinforcement) water intake varied from 82 to 102 oz. During that phase Participant 4

met the criteria every day. In the next condition (combination of positive and negative

reinforcement) the amount of water ranged between 81 and 93 oz. and all of the

criteria were met. Finally, in the last condition (negative reinforcement) water intake

varied between 84 and 90 oz. and again Participant 4 met the criteria every day.

23

The number of steps walked in baseline varied from 5531 to 17385 steps.

Similarly to the water intake the data showed a big increase from the last data point of

the initial phase (12489 steps) to the first one of intervention (22375 steps). In the

first intervention condition (positive reinforcement) the number of steps varied

between 22375 and 27384. During that phase Participant 4 met the criteria every day.

In the next phase (combination of positive and negative reinforcement) the number of

steps ranged from 22368 to 28249 and all of the criteria were met. Finally in the last

phase (negative reinforcement) the number of steps varied from 22256 to 23118 and

Participant 4 met the criteria every day.

In Participant’s 4 walking data there are 2 data points which are significantly

different from the main data path. Participant 4 reported verbally that on day 10 and

20 scores were high and Participant 4 did 27384 and 28249 respectively because he

participated in marathons.

Participant’s 4 weight did change. From the initial 173.4 lbs. it increased to

the 178 lbs. for the final weight. This change is within day to day body weight

fluctuation.

Table 3 shows the summary of the average number of steps and amount of

water for each participant. These data show that Participants 1 and 3, in general,

scored better in SR– condition and Participants 2 and 4 in general scored better in

SR+ & SR – condition and SR+ condition.

24

Table 3

The average number of steps or amount of water during particular conditions

Participant Behavior

SR + average SR – average SR + & SR –

number

(over 7 days) (over 7 days) average (over 7 days)

1

2

3

4

Walking

(steps)

Water intake

(oz.)

Walking

(steps)

Water intake

(oz.)

Walking

(steps)

Water intake

(oz.)

Walking

(steps)

Water intake

(oz.)

6265

6630

6529

57,1

58,4

57,7

18746

13882

16677

157,7

118,7

142,3

6208

6326

5146

64,6

64,9

65,7

23566

22513

23910

90,7

87,6

87,1

Social validity questionnaires which were introduced separately for each of

the behaviors indicate the following; 3 out of 4 participants agreed that this study was

beneficial for them. All of them stated that they would recommend this program to

their friends and were motivated to participate. None of the participants reported

dishonesty during data collection. All of the participants claimed that the rules they

had to follow during the experiment were clear and 2 out of 4 participants stated that

the amount of money available for daily goals corresponded with necessary effort and

2 neither agreed nor disagreed. When asked about willingness to use this program in

order to increase other behaviors the answers were varied and ranged from strongly

disagree to strongly agree (see Appendix C).

DISCUSSION

Across all of the participants and behaviors there is a fairly large increase

from baseline to intervention, which suggests good control over the behaviors. A

visual analysis of the data does not reveal any significant differences in effectiveness

of different types of reinforcement since the aforementioned change is maintained

across all of the conditions. These results are different from the previous findings of

DeLeon et al. (2001) and Bouxsein et al. (2011). They found that, at least in regards

to compliance, positive reinforcement is more effective than negative reinforcement

but the combination of both is the most effective approach. There are several possible

reasons for these discrepancies.

Firstly, it should be noted that DeLeon et al. (2001) as well as Bouxsein et al.

(2011) attempted to decrease escape maintained behaviors by increasing compliance

to demand. This is important because any positive reinforcement such as access to

tangibles was by default more reinforcing than negative reinforcement since it also

included a break from the demand necessary for delivery of reinforcement and time to

eat the edibles, listen to music. In the current study the amount of reinforcement ($2)

and hence its value was the same for all of the conditions. Thus one of the

explanations could be that the differences among reinforcement effectiveness in

DeLeon et al. (2001) and Bouxsein et al. (2011) studies were not a result of the

different nature of positive and negative reinforcement but, rather, the actual

difference in value of the reinforcers.

25

26

On the other hand, a part of the current data seems to be consistent with

previous findings (DeLeon et al., 2001; Bouxsein et al., 2011). For 2 out of 4

participants the data show that the behavior in the negative reinforcement phase was

stable, usually just above the daily criteria. Positive reinforcement and combination of

positive and negative reinforcement conditions produced more variability in data.

Participants were more likely to not only meet the criteria but also exceed it by a fair

amount sometimes. However, the interesting issue was that these two participants

(number 2 and 4) were men and when we look at the other two, which were women

(number 1 and 3) the situation is almost the opposite. They were more likely to

exceed the criteria in negative reinforcement condition alone then in conditions which

included positive reinforcement. However it is important to emphasis that these are

only observations and any generalized assumptions should not be made; especially,

taking into account the small number of participants and specific narrow population.

Interestingly, all of the participants reported verbally at the last meeting that

they were feeling most motivated during the combination of positive and negative

reinforcement condition. For summary see Table 3.

Another difference between this study and previous research was the

participants. It seems reasonable to claim that particular arrangements of

reinforcement contingencies could have a different impact on typically developing

adults (university students) in comparison to the children with Autism or Down

syndrome. It is likely that the former had a much more extensive history with

27

aversive control than the latter which could have contributed to the similar results

across all of the phases.

The other possible explanation of these results is the fact that the independent

variable was a verbal behavior manipulation. This means that there was no actual

difference in contingency among conditions; it was only the matter of the words used

to describe the rule. The actual consequence was the same everyday [i.e. participants

could earn $2 either by meeting the criteria (positive reinforcement) or by avoiding

the loss of previously assigned money but that money was not in their possession

(negative reinforcement)]. There is a chance that the participants were responding to

the underlying contingencies not the rules that they were given. To test that

possibility future researchers should introduce a negative reinforcement condition

where participants could actually lose something of value (e.g., their own money). It

could be realized by asking them to deposit a certain amount of money prior to the

study which would be given back only when they met the criteria. It is also worth

mentioning that following debriefing, all of the participants reported that they felt

differently in each of the conditions and that they were focusing on the described rule.

They claimed that they were not aware of the artificial difference among phases

created only by wording so they behaved in accordance with the actual contingency.

In regards to the independent variable, even if participants reported via the

social validity survey (see Appendix C) that the amount of money corresponded with

the effort necessary to meet the criteria, it is not clear if the value was too high or too

low to reveal differences since it was arbitrarily determined based on available

28

resources. Simultaneously, perhaps if the criteria itself was higher and hence more

difficult to meet, then it would be possible to observe potential differences. Thus, the

issue should be addressed in future research.

Another important issue is the dependent variable. As mentioned, it is possible

that the effort necessary to complete the task can modulate the value of

reinforcement. This is consistent with DeLeon et al. (2001) results where the

participant changed his preference in regards to the type of reinforcement based on

the increasing task difficulty. Thus, a factor that could have influenced data is not

only the actual amount of reinforcement but its relative value that could be interfered

by the required effort to complete the task. In this study all of the participants

commented that drinking water was easier when compared to walking which required

time spent on additional activities to meet the criteria and often interfered with the

type of participant’s work. Future studies should address that issue by using behaviors

of equal effort.

Also, the data collection system should be discussed. Despite the attempt to

control self-recording validity, there are several issues which should be considered

when analyzing data. There was no objective control over the participant’s honesty.

The applications used did not offer automatic online data tracking or even automatic

data recording (it is currently impossible to easily measure someone’s water intake

without the participant’s contribution). Thus, the only system of control was the

participants’ every day e-mails with screen shots of the daily achievement in

application. However, all of the participants, in the anonymous online survey,

29

reported being honest in data collection (see Appendix C) this should be treated with

caution. Future research should test that issue perhaps using more sophisticated

technology which would allow eliminating the possibility of participant dishonesty.

Taking these issues into account it is possible that data from both behaviors

are misleading. However, it is important to note that the method of data collection

was chosen because of the type of population (which is difficult to observe directly)

as well as an attempt to keep the situation as close to the natural environment as

possible. Applied research involves many compromises over laboratory research

methodology, however the use of technology seems to be a promising direction in the

area of self-management studies.

Each phase in this study lasted only one week, it would be beneficial for

future researchers to extend the period of time when a particular reinforcement is in

place. It is possible that in a longer term perspective the differences are more

significant and particular types of reinforcement have some additional side effects.

It would be also interesting to see how the data would look like if there was no

learning effect, since all of the participants reported that with time the behaviors were

easier to perform. Perhaps future studies should address that issue by introducing

different behaviors for each of conditions but which require equal effort or by

changing criteria to keep the necessary effort consistent by contracting against

learning effect. These could not be incorporated in this research due to limited time

and resources.

30

In conclusion, despite previous research that suggested differences in the

effectiveness of different types of reinforcement, the current study does not support

those findings. The data obtained in this research shows no large differences between

different reinforcement contingencies. However, the study did show that

implementing a relatively low cost reinforcement contingency did seem to increase

both exercise and water drinking. Further research may be able to clarify the best type

of reinforcement system, as well as maximize the behavioral change.

REFERENCES

32

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and

code of conduct. Retrieved from http://apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

Bedesem, P. L., & Dieker, L. A. (2014). Self-monitoring with a twist: using cell

phones to CellF-monitor on-task behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior

Interventions, 16(4), 246-254. doi:10.1177/1098300713492857

Blood, E., Johnson, J. W., Ridenour, L., Simmons, K., & Crouch, S. (2011). Using an

iPod Touch to Teach Social and Self-Management Skills to an Elementary

Student with Emotional/Behavioral Disorders. Education & Treatment of

Children, 34(3), 299-321.

Bouxsein, K. J., Roane, H. S., & Harper, T. (2011). Evaluating the separate and

combined effects of positive and negative reinforcement on task

compliance. Journal Of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(1), 175-179.

Burgio L, D., Whitman T, L., & Johnson M, R. (1980). A self-instructional package

for increasing attending behavior in educable mentally retarded

children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13(3), 443-459.

Catania, A. C. (1975). The myth of self-reinforcement. Behaviorism, 3192-199.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The. (2014) How much physical activity

do adults need? Retrieved from

http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/adults.html

33

Cihak, D. F., & Gama, R. I. (2008). Noncontingent escape access to selfreinforcement to increase task engagement for students with moderate to

severe disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental

Disabilities, 43(4), 556-568.

Dean, M. R., Malott, R. W., & Fulton, B. J. (1983). The effects of self-management

training on academic performance. Teaching Of Psychology, 10(2), 77.

DeLeon, I. G., Neidert, P. L., Anders, B. M., & Rodriguez-Catter, V. (2001). Choices

between positive and negative reinforcement during treatment for escapemaintained behavior. Journal Of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(4), 521-525.

doi:10.1901/jaba.2001.34-521

Duarte, A. M., & Baer, D. M. (1994). The effects of self-instruction on preschool

children's sorting of generalized in-common tasks. Journal of Experimental

Child Psychology, 57(1), 1-25. doi:10.1006/jecp.1994.1001

Epstein, R. (1997). Skinner as self-manager. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 30545-568.

Fritz, J. f., Iwata, B. A., Rolider, N. U., Camp, E. M., & Neidert, P. L. (2012).

Analysis of self-recording in self-management interventions for

stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(1), 55-68.

Glynn, E. L. (1970). Classroom applications of self-determined

reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 3(2), 123-132.

34

Grandjean, A. (2004). Water Requirements, Impinging Factors, and Recommended

Intakes. Retrieved from

http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/nutwaterrequir.pdf

Goldiamond, I. (1976). Self-reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 9(4), 509-514. doi:10.1901/jaba.1976.9-509

Gulchak, D. J. (2008). Using a mobile handheld computer to teach a student with an

emotional and behavioral disorder to self-monitor attention. Education &

Treatment of Children, 31(4), 567-581.

Hammond, R. A., & Levine, R. (2010). The economic impact of obesity in the United

States. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity : Targets and Therapy, 3,

285–295. doi:10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384

McCarl, J. J., Svobodny, L., & Beare, P. L. (1991). Self-recording in a classroom for

students with mild to moderate mental handicaps: Effects on productivity and

on-task behavior. Education & Training in Mental Retardation, 26(1), 79-88.

Muckelbauer, R., Sarganas, G., Grüneis, A., & Müller-Nordhorn, J. (2013).

Association between water consumption and body weight outcomes: a

systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 98(2), 282299. doi:10.3945/ajcn.112.055061

Newman, B., Buffington, D. M., & Hemmes, N. S. (1996). Self-reinforcement used to

increase the appropriate conversation of autistic teenagers. Education &

Training in Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities, 31(4), 304309.

35

Newman, B., Tuntigian, L., Ryan, C. S., & Reinecke, D. R. (1997). Self-management

of a DRO procedure by three students with autism. Behavioral

Interventions, 12(3), 149-156.

NorthPark.Android. (2015). Water Your Body (Version 3.081) [Mobile application

software]. Retrieved from https://play.google.com/store?hl=en

Noom Inc. (2015). Noom Walk Pedometer: Fitness (Version 1.1.1) [Mobile

application software]. Retrieved from https://play.google.com/store?hl=en

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan.

Stasolla, F., Perilli, V., & Damiani, R. (2014). Self-monitoring to promote on-task

behavior by two high functioning boys with autism spectrum disorders and

symptoms of ADHD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(5), 472-479.

doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2014.01.007

World Health Organization, The. (2015) Obesity and overweight [Fact sheet No311].

Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

APPENDICES

37

APPENDIX A

CONSENT FORM

1. This research will examine the effectiveness of self-management techniques in

increasing daily walking and water intake. If you agree to participate, you will

be asked to follow the instructions given to you by researcher during the

initial training and throughout the course of the study.

2. You are free to discontinue your participation at any time without penalty.

Even if you withdraw from the study, you will receive any entitlements that

have been promised to you in exchange for your participation, such as extra

credit (if available) and free water bottle.

3. Participation in this research study does not guarantee any benefits to you.

However, possible benefits include the fact that you may learn something

about how research studies are conducted and you may learn something about

this area of research (i.e. self-management techniques and their possible

application in everyday life).

4. You will be given additional information about the study after your

participation is complete.

5. If you agree to participate in the study, you will be also asked to download

two free applications to your phone and to provide to the researcher the data

collected by them. Any personal information obtained during this process of

data collection will be kept on the researcher’s computer in a separate folder

protected by a password and will be accessible only to the researcher or his

supervisor. Any personal information downloaded to the researcher’s

smartphone will be deleted immediately that information has been transferred

to the computer folder.

6. If you agree to participate in the study, due to the way of communication

(sharing of information via smartphone) with researcher, you will take

responsibility for any additional data and messaging fees which may be

potentially associated with your participation.

7. If you agree to participate in the study, you will be asked to attend the initial

session which will last approximately 2 hours and during that time the

researcher will provide any necessary information to participate in this study.

Additionally, your weight will be measured at the beginning and at the end of

the study. The subsequent meetings will last no more than half an hour.

38

Furthermore, since walking and drinking water are relatively unobtrusive

behaviors and can be performed throughout the day, there is no specific time

frame and amount of time you need to spend on them every day, thus you are

free to reach your goals at any time during each 24 hour period.

8. All data from this study will be kept from inappropriate disclosure and will be

accessible only to the researcher and his faculty advisor. To assure

confidentiality any information which could allow to identify particular

individual will be replaced with artificial data.

9. The present research is designed to reduce the possibility of any negative

experiences as a result of participation. Risks to participants are kept to a

minimum. However, if your participation in this study causes you any

concerns, anxiety, or distress, please contact the Student Counseling Center at

(209) 667-3381 to make an appointment to discuss your concerns.

10. This research study is being conducted by Rafał S. Gebauer. The faculty

supervisor is

Dr. William Potter, Professor and Chair, Department of Psychology and Child

Development, California State University, Stanislaus. If you have questions or

concerns about your participation in this study, you may contact the

researchers through Dr. Potter at (209)667-3518.

11. You may obtain information about the outcome of the study at the end of the

academic year by contacting Rafał S. Gebauer at rgebauer@csustan.edu.

12. If you have any questions about your rights as a research participant, you may

contact the Campus Compliance Officer of California State University

Stanislaus at IRBadmin@csustan.edu.

13. You will be provided with a blank, unsigned copy of this consent form at the

beginning of the study.

14. By signing below, you confirm that you are in a good health condition and

you have no contraindications for participating in the study that involves

walking. You also agree to immediately inform researcher about any health

problems during the study.

15. By signing below, you confirm your availability for the period of 31 days

starting from the initial session.

16. By signing below, you attest that you are 18 years old or older.

39

17. By signing below, you are indicating that you have freely consented to

participate in this research study.

PARTICIPANT’S SIGNATURE:

DATE: ___________

40

APPENDIX B

SOCIAL VALIDITY QUESTIONNAIRE

Social Validity Questionnaire - Water Intake

*Required

I think that this study was beneficial for me. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I especially liked the condition in which I could gain money every time I drank

water. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I especially liked the condition in which I could lose money every time I did not

drink water. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I especially liked the condition in which I could gain money every time I drank

water and could lose money every time I did not drink water. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I would recommend this program to my friend. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I was motivated to participate in this study. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

I cheated on data collection. *

1

2

3

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

4

5

Strongly Agree

The rules which I should follow during experiment were clear. *

1

2

3

4

5

41

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

The amount of money available for daily goal corresponded with necessary effort. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

There were things I would change to increase effectiveness of that intervention. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

What?

I would like to carry on this program to constantly improve or maintain my water

intake. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I would like to use this program in order to increase my other behaviors. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Please provide any additional comments:

Strongly Agree

42

Social Validity Questionnaire - Walking

*Required

I think that this study was beneficial for me. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I especially liked the condition in which I could gain money every time I did walk. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I especially liked the condition in which I could lose money every time I did not

walk. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I especially liked the condition in which I could gain money every time I did walk

and could lose money every time I did not walk. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I would recommend this program to my friend. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I was motivated to participate in this study. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

I cheated on data collection. *

1

2

3

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

4

5

Strongly Agree

The rules which I should follow during experiment were clear. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

The amount of money available for daily goal corresponded with necessary effort. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

There were things I would change to increase effectiveness of that intervention. *

1

2

3

4

5

43

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

What?

I would like to carry on this program to constantly improve or maintain my

walking. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

I would like to use this program in order to increase my other behaviors. *

1

2

3

4

5

Strongly Disagree

Strongly Agree

44

APPENDIX C

SOCIAL VALIDITY QUESTIONNAIRE – RESULTS

Social Validity Questionnaire - Water Intake – Results

1 - strongly disagree; 2 – disagree;3 – neither disagree nor agree; 4 – agree; 5 – strongly agree

45

Why?

to be part of an actual study and to get rewarded with

money

It allowed me to earn money as well as do something

for my health.

for the money and to stay hydrated

I was interested in the results that it may bring

46

Please provide any additional comments:

This program has been very helpful to me to increase my water intake. Before

it was very hard for me to drink more than a bottle of water a day. Now I find

myself getting more thirsty during the day and wanting to drink water

47

Social Validity Questionnaire – Walking

1 - strongly disagree; 2 – disagree;3 – neither disagree nor agree; 4 – agree; 5 – strongly agree

48

Why?

the step goals were a little harder to reach because my occupation requires me

to be seated a lot so I had to walk around more often than I normally would

I earned money and did something to better my help.

for the money

I currently have an office job so I do not walk a lot. I was interested in the

results that could come from walking more

49

Please provide any additional comments:

The only problem I found was that at times the app used to keep track of the

steps would either give me steps for no reason, or just not keep track of the

steps I took properly.