Marketing Channels Delivering Customer Value

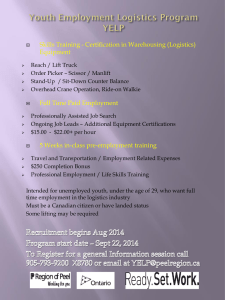

advertisement