Agenda and Presentation Materials

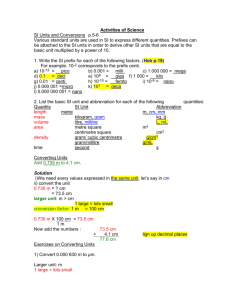

advertisement