SeHablaEspanol - WordPress.com

advertisement

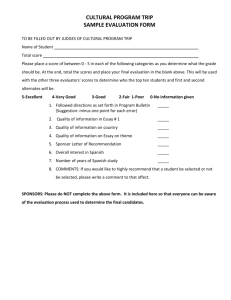

316

~

Definition

examples of this logic of elimination in Barry's essay, such as his definition of

guys as "scum" in paragraph 31.

TAN YA BARRIENTOS

SE

3. Why do you think Barry is so careful to specify the gender of God in paragraph 17? What AUDI ENCE does he have in mind here?

4. From reading Barry's title, you might expect "Guys vs. Men" to be primarily

a COMPARISON AND CONTRAST essay. Where and why does Barry switch from

drawing a comparison between the two kinds of males to defining one kind to

the exclusion of the other?

5. Barry's humor often comes from his use of specific EXAMPLES, as in "violent crime, war, spitting, and ice hockey" (3). Point out where his scrupulous

examples help define specific terms. What would this essay be like without

all the examples? What is Barry's PURPOSE in being (or pretending to be) so

rigorous?

~

WORDS AND FIGURES OF SPEECH

Tanya Barrientos (b. 1960) is a novelist , a columnist for the Philadelphia

Inquirer, and a writing teacher at Arcadia U niversity_She is t he aut hor of

Frontera Street (2002) and Family Resemblance (2003)_ "Se H abla

Espafiol" is from a 2004 issue of the bilingual m agazine Latina_The title

refers to the sign, often seen in store windows, announcing "Spanish is

spoken" here. In this essay, Barrientos raises a basic question of selfdefinition and ethnic identity: C an a woman born in Guatemala who

grew up in the United States speaking English instead of Spanish be

legitimately considered a Latina?

~

1. How does Barry DEFINE "male" (2)? How about "manly" (2)? So, according

to Barry's definitions, is "manly male" an OXYMORON? (Barry would probably

make a joke here, one that would not be complimentary either to males or to

oxen.)

2. How would you define "loons" (3)? How do they differ from "goobers" (3)?

3. Why does Barry capitalize "Big Trouble" in paragraph 26?

4. Translate the following Barry phrase into standard English: "one humongous

and spectacularly gizmo-intensive item of hardware" (15).

~

H ABLA E s PANOL

FOR WRITING

1. Rightly or wrongly, Barry has been called a humorist. How would you

DEFINE one? Make a list of the distinguishing characteristics that make a good

humorist in your view, and give EXAMPLES of humorists who you think represent

these characteristics (you might want to use Barry as an example, or not).

2. How would you define "guys"? What characteristics does Barry leave out?

Can a female be a "guy" (as in "When we go shopping, my grandmother is just

one of the guys")? Write an essay setting forth your definition of "guys." Or

choose another gender term (such as men, women, girls, or girlfriends), and write

an essay that gives "another way to look" at gender through your definition of

this term .

he man on the other end of the phone line is telling me th e classes

I've called about are first-rate: native speakers in charge, no m ore

than six students per group. I tell him that will be fine and yes, I' ve

studied a bit of Spanish in the past. H e asks for my name and I supply

it, rolling the double "r" in "Barrientos" like a pro. T hat's when I hear

the silent snag, the momentary hesitation I've come to expect at this part

of the exchange. Should I go into it again? Should I explain, tP.e way I

have to half a dozen others, that I am Guatemalan

but pura

gringa 1 by circumstance?

. ::: -~· -·.~ ' ·· ~ .

This will be the sixth time I've signed up to learn the lang-uage my

' workparents speak to each other. It will be the sixth time l' ve ~bought

books and notebooks and textbooks listing 50 1 conjugated verbs in

alphabetical order, in hopes that the subjunctive tense wilJ finally take

root in my mind. In class I will sit across a table from the' "native

speaker," who will wonder what to make of me. "Look," I'll want to say

T

·J?y..-b.irth

1. Gringa, which is the feminine form of gringo, is used to refer t o someone of nonLatina background.

~

317

~

2

318

4

6

9

~

Defi nition

(but never do). "Forget the dark skin. Ignore the obsidian eyes . Pretend

I'm a pink-cheeked, blue-eyed blonde whose name tag says 'Shannon."'

Because that is what a person who doesn't innately know the difference

between corre, corra, and carr{ is supposed to look l~ke, isn't it?

•

<~ ca,w.e to the United States in 1963 at age 3 with my family and

immediat~lY stopped speaking Spanish . College-educated and seamlessly .

bilingtl'al w,hen they settled in west Texas, my parents (a psychology professm; ancf an artist) wholeheartedly embraced the notion of the American melt'ing. pot, They declared that their two children would speak

nothing·b~·t ii{gle~. They'd read in English, write in English, and fit into

AngeJo :Society ·beautifully.

It sounds politically incorrect now. But America was not a hyphenated nation back them. People who called themselves Mexican Americans or Afro-Americans were considered dangerous radicals, while lawabiding citizens were expected to drop their cultural baggage at the

border and erase any lingering ethnic traits.

To. be honest, for most of my childhood I liked being the brown

girl who defined expectations. When I was 7, my mother returned my

older brother and me to elementary school one week after the school

year had already begun. We'd been on vacation in Washington, D.C. ,

visiting the Smithsonian, the Capitol, and the home of Edgar Allan Poe.

In the Volkswagen on the way home, I'd memorized "The Raven," and I

would recite it with melodramatic flair to any poor soul duped into sitting through my performance. At the school's office, the registrar

frowned when we arrived.

"You people. Your children are always behind , and you have the

nerve to bring them in late?"

"My children," my mother answered in a clear, curt tone, "will be

at the top of their classes in two weeks."

The registrar filed our cards, shaking her head.

I did not live ,in an neighborhood with other Latinos, and the public school I attended attracted very few. I saw the world through the

clear, cruel vision of a child . To me, speaking Spanish translated into

being poor. It meant waiting tables and cleaning hotel rooms. It meant

being left off the cheerleading squad and receiving a condescending

smile from the guidance counselor when you said you planned on

Barrientos I Se Habla Esparw l . . 3 19

becoming a lawyer or a doctor. M y best friends' names were H eidi and

Leslie and Kim. They told me I didn't seem "M exican" to them. and I

took it a as compliment. I enjoyed looking into the faces of L atino store

clerks and waitresses and, yes, even our maid and saying "Yo no lu:Wlo

espaiiol." It made me feel superior . It m ade me feel American. l t mad e

me feel white. I thought if I stayed away from Spanish, stereotypes

would stay away from me.

Then came the backlash. During the two decades when I'd

worked hard to isolate myself from the stereotype I'd const ructed in

my own head, society shifted . The nation changed its views on ethnic

identity. College professors started teaching history through M rican

American and Native American eyes. C hildren were told to forget

about the melting pot and picture America as a multicolored q uilt

instead. Hyphens suddenly had muscle, and I was left wondering

where I fit in.

The Spanish language was supposedly the glue t hat held the new

Latino community together. But in my case it was what kept me apart. I

felt awkward among groups whose conversations flowed in and out of

Spanish. I'd be asked a question in Spanish and I'd have to answer in

English, knowing this raised a mountain of questions. I wanted to call

myself Latina, to finally take pride, but it felt like a lie. So I set out to

learn the language that people assumed I already knew.

After my first set of lessons, I could function in the present tense.

"Hola , Paco. iQue tal? iQue color es tu cuademo? El mio es azul. " M y

vocabulary built quickly, but when I spoke, my tongue felt thick inside

my mouth- and if I needed to deal with anything in the future or the

past, I was sunk. I enrolled in a three-month submersion program in

Mexico and emerged able to speak like a sixth-grader with a solid C

average. I could read Gabriel Garcia Marquez 2 with a Spanish -English

dictionary at my elbow, and I could follow 90 percent of the melodrama

on any given telenovela. 3 But true speakers discover my limitation s the

moment I stumble over a difficult construction, and that is when I get

2. Columbian novelist and short-story writer (b. 1928).

3. Spanish-language TV soap opera.

320

13

14

~

Barrientos I Se I-Iabla Espafiol

Definitio n

the look. The one that raises the wall between us . The one that makes

me think I'll never really belong. Spanish has become a litmus test

showing how far from your roots you've strayed .

My bilingual friends say I make too much of it. They tell me that

rriy Ou~te~alan heritage and unmistakable Mayan features are enough

to legitimize my m embership in the Latin American club. After all, not

all Poles sp~ak Polish. Not all Italians speak Italian. And as this nation

grows 1morl and more Hispanic, not all Latinos will share one language.

1

But ) · don t ~el~~~~ them.

'Ihere'".mti'S.t·he other Latinas like me. But I haven 't met any. Or, I

should, sil:y,.. -ha~en' t met any who have fessed up. Maybe they are

secretly struggling to fit in, the same way I am. Maybe they are hiring

tutors and listening to tapes behind locked doors, just like m e. I wish we

all had the courage to come out of our hiding places and claim our rightful spot in the broad Latino spectrum. Without being called hopeless

gringas. Without h aving to offer apologies or show remorse.

If it .will help, I will go first .

Aqui estoy. Spanish-challenged and pura Latina.

t

15

16

~

FoR DISCUSSION

~

1. Tanya Barrientos is not a native speaker of Spanish, though both of her parents were. Why didn't they encourage her to learn the language as a child?

Should they have? Why or why not?

2. According to Barrientos, how were "hyphenated" Americans in general

DEFINED when she and her family first came to the United States from

Guatemala in 1963 (4)? How did young Barrientos herself define Latinos who

spoke Spanish?

3. In the decades following her arrival in the United States, says Barientos, societal views toward ethnic identity "shifted" (1 0). W hat are some of the more significant aspects of that shift, according to Barrientos?

4. In your opinion, is Barrientos a legitimate member of "the Latin American

club" (1 3)? That is, can she and others with similar backgrounds rightfully

define themselves as Latinas or Latinos? Why or why not?

~

4

321

STRATEGIES AND STRUCTURES

~

1. What is Barrientos's PURPOSE in "Se Habla Espaiiol": to explain why she does

not speak Spanish with the fluency of a native speaker? to persuade readers that

she is a true Latina? to DEFINE the ambiguous condition of being both "Spanishchallenged and pura Latina" (16)? Explain.

2. Is Barrientos's essay aimed mainly at a multilingual AUDJENCE or a largely

English-speaking one? Why do you say so?

3. Throughout her essay, how does Barrientos use the Spanish language itsclf to

help defin e who and what she is? Give several examples that you find particularly effective.

4. Where and how does Barrientos construct a stereotypical definition of "Latin

American?" Where and how does she reveal the shortcomings of this definition?

5. Barrientos's essay includes many NA RRATIVE elements. What are some of

them, and how do they help her to define herself and her condition?

~

WORDS AND FIGU RES

OF

SPEECH

~

1. Once defined as a "melting-pot," the United States, says Barrientos, is now a

"multicolored quilt" (10). What are some of the implications of this shift in

METAPHORS for national diversity?

2. When Barrientos refers to the Spanish language as "glue," is she avoiding

or getting stuck in one (11 )? Explain.

3. In printing, a stereotype was a cast metal plate used to reproduce blocks of

type or crude images. How does this early meaning of the term carry over into

the modern definition as Barrientos uses it (10)?

4. Barrientos sometimes groups herself with other "Latinos," sometimes with

other "Latinas" (9 , 14 ). Why the difference?

CLICHEs

~

FoR WR IT ING

1. Write a paragraph or two about an incident in which someone DEFINED you

on the basis of your choice of words, your accent, or some other aspect of your

speech or appearance.

2. Write an essay about your experience learning, or attempting to learn, a language other than your native tongue- and how that experience affected your

own self-definition or cultural identity.