File

advertisement

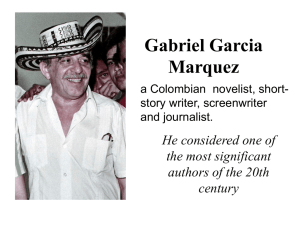

IB English A1 Higher Level World Literature Assignment 1 Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez The Author’s Use of Weddings to Criticize the Stereotype of Latin American Women Seoul Foreign School, South Korea Word Count: 1,500 1 The Role and Function of Weddings In many Latin American cultures, weddings are traditionally regarded as very important social occasions, and often times marriages are arranged by the parents of the bride without the bride having any choice in whom she will marry. Mexican writer Laura Esquivel, through the wedding of Rosaura and Pedro and the contrasting wedding of Alex and Esperanza in her novel Like Water for Chocolate, criticizes the traditional view that women are inferior and not entitled to much opinion. In the same manner, Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez, through the wedding of Bayardo San Román and Angela Vicário in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, voices his disdain of the attitudes towards women in Latin American society. In Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate, the wedding of Rosaura and Pedro is used to criticize the stereotype of women as merely the possession of the husband by portraying it in a condemnatory way. Pedro and Tita love each other, but Tita’s mother, Mama Elena, insists that her eldest daughter Rosaura be wed first. This is so that Tita can stay unmarried and take care of her when she gets old. Esquivel uses the character of Chencha, the maid, to convey her opinion on the matter when Chencha says, “Your ma talks about being ready for marriage like she was dishing up a plate of enchiladas! And the worse thing is, they’re completely different! You just can’t switch tacos and enchiladas like that!” (14). Here, Esquivel uses the simile between Mama Elena offering her daughter up for marriage and serving a plate of food, which equates her daughters to mere inanimate objects that are given to others for their enjoyment. This simile used by Esquivel also indicates no consideration whatsoever for the feelings or emotions of Tita and Rosaura, since a plate that is being served is given no voice. Esquivel uses this image to portray the typical treatment of women in many Latin American societies as merely possessions. Another instance where Esquivel uses the wedding of Rosaura and Pedro to criticize the role of women is when Tita and Nacha are castrating chickens in order to prepare them for the wedding banquet. Tita, bitter over her sister marrying the man she loves, starts shaking while castrating the chickens, to which Mama Elena asks if she is well. Esquivel uses Tita’s stream of consciousness to convey her disdain for her forced submission by saying, “when they had chosen something to be neutered, they’d made a mistake, they should have chosen her. At least then there would be some justification for not allowing her to marry and giving Rosaura her place beside the man she loved” (27). Here, Tita is wishing that she had been neutered instead of the chickens, so that a valid excuse could be put forth for her not being allowed to marry. Esquivel uses this to convey her criticism that the typical view of 2 women as inferior and not entitled to their own will is not excusable. Only a severe physical mutilation such as castration would satisfactorily impede Tita from being able to marry Pedro. Thus, in the marriage of Pedro and Rosaura Esquivel disapproves of the stereotypical portrayal of women in Latin American societies. In a similar way to what Esquivel does, Gabriel García Márquez in his novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold also denigrates the typical view of women in Latin American society through the wedding of Angela Vicário and Bayardo San Román. Bayardo is a mysterious man who appears in town one day. Not too long after, he seeks the hand of young Angela Vicário, the youngest daughter in the Vicário family. Márquez, like Esquivel, criticizes the lack of free choice that women have by using negative diction when he writes that she “never forgot the horror of the night on which her parents and her older sisters with their husbands…imposed on her the obligation to marry a man whom she had barely seen” (34). Here, Márquez uses the noun ‘horror’, which has the connotation of something extremely appalling and terrifying, indicating that the thought of marrying a man she has never seen truly strikes fear in Angela to a great extent. The verb ‘imposed’ also has the connotation of a forced action that disregards the will of its object, which points toward the fact that Angela had no choice in the matter of marrying Bayardo. Additionally, Márquez also uses the noun ‘obligation’ to classify Angela’s marriage to Bayardo, which also connotes something that must be done regardless of her feelings. By using these pejorative words, Márquez is conveying to the reader his disparaging view on the traditional view of women in Latin American society in the same way that Esquivel does. Another instance where Márquez uses the marriage between Angela Vicário and Bayardo San Román to criticize the image of women is when Angela raises the issue of a loving marriage with her mother. Márquez writes that “Angela Vicário only dared hint at the inconvenience of a lack of love, but her mother demolished it with a single phrase: “Love can be learned too” (34-35). Here, Márquez again uses negative diction to portray his opinion on the stereotypical view of women by employing the noun ‘inconvenience’, which in this case indicates a bothersome detail of little importance and that carries little weight in the decision. The fact that Angela’s mother sees love in marriage as a mere ‘inconvenience’ is indicative that she disregards Angela’s desire for its presence. As seen in Esquivel’s novel with Mama Elena, Márquez emphasizes this by using Angela’s mother’s response: “Love can be learned too”, which shows the impersonal treatment of marriage that is the social custom in the novel. Angela herself is not considered into the equation when setting up the marriage, indicating that her thoughts are not important. Márquez also uses the verb ‘demolished’, a strong verb 3 that suggests a rapid and violent destruction of, in this case, Angela’s desire to have a marriage with love. Through his use of negative diction in portrayal of the wedding of Angela Vicário and Bayardo San Román, therefore, Márquez condemns the typical view of women in Latin American society just as Esquivel does. However, one thing that Esquivel does that Márquez does not is provide an alternate depiction of the ideal treatment of women. In addition to using the wedding of Rosaura and Pedro to criticize the role of women, Laura Esquivel also uses the contrasting wedding of Alex and Esperanza to the same effect by portraying it as the ideal marriage in which both partners are equal. Esquivel describes Alex and Esperanza as being “attracted at the moment they met” (238), an expression which indicates that there are mutual, true feelings between them, unlike the unilateral pursuit between Pedro and Rosaura. Esquivel goes on to say that “Tita knew that Alex and Esperanza would be bound together forever” (238), which points towards the fact that, being attracted to each other, their feelings for each other are strong enough to bind them together, something which is also absent in the marriage between Pedro and Rosaura. Esquivel uses this contrast to criticize the disregard of women’s opinions and, going beyond Márquez, provide an alternate way of going about it. Esquivel emphasizes the benefits of equal treatment of women as opposed to the stereotypical inconsideration of them by describing Tita’s impression of Esperanza at the wedding when she says, “How proud she felt to see Esperanza so self-confident, so intelligent…so happy” (240). The adjectives chosen by Esquivel, “self-confident”, “intelligent”, and “happy” all have positive connotations associated with a happy disposition. By using these adjectives, Esquivel is conveying a message that equal treatment of women in the marriage provides happiness and confidence, in contrast with the stereotypical unequal marriage of Pedro and Rosaura that does not. Thus, Laura Esquivel uses the wedding of Alex and Esperanza in contrast to that of Pedro and Rosaura in order to express disapproval of the traditional regarding of women as inferior in the same way as Márquez does, but also to illustrate an alternate, better way of treating women – as equal. In an ever-changing Latin American society, the stereotypical view of women as inferior to men can still be seen. Today, however, many people frown upon this concept, and this opinion can be seen in Latin American literature as well. Both Laura Esquivel, in her episodic novel Like Water for Chocolate, and Gabriel García Márquez, in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, criticize the notion of the inferiority of women through the use of the weddings of their characters. Additionally, Esquivel, no doubt given the advantage of writing from a female perspective, also provides an alternate view of how women should be treated 4 instead. Although the struggle for equal rights can not be said to have completely prevailed in Latin America today, these two novels that share intricate similarities no doubt stand as titles famous for their criticism of the traditional view of women, among other things. And as the great William Shakespeare once said, “Hasty marriage seldom proveth well”. Word Count: 1,500 5 Works Cited Esquivel, Laura. Like Water for Chocolate: A Novel in Monthly Installments, with Recipes, Romances and Home Remedies. Christensen, Carol and Thomas: transl. 1st Ed. New York: Anchor, 1995. Print. Márquez, Gabriel García. Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Rabassa, Gregory: transl. 1st Ed. New York: Random House, 2003. Print.