Thomas 1

advertisement

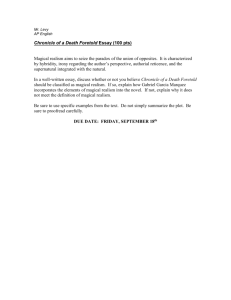

Thomas 1 Candidate Number: 0847-000-0000 Michelle R. Thomas Language A1 World Literature Paper 1, HL 9 March 2006 Magical Realism in The House of the Spirits and Like Water for Chocolate Need help with your problems? Just consult the spirits of the three-legged table. Having trouble getting the tamales to cook? They are probably angry because people are arguing, so just sing to them and it will make them feel better. These things are not possible in real life, and yet seem to be conventional in these two novels. This effect is accomplished by Allende and Esquivel because both The House of the Spirits and Like Water for Chocolate incorporate magical realism into their plots to enhance the characterization of the protagonists as well as the antagonists in their stories. Talks about Clara here… One antagonist who is especially evident in The House of the Spirits is Esteban Garcia. His character is the epitome of evil; this becomes obvious when he agrees as a young boy to aid Esteban Trueba in his attempt to murder Pedro Tercero Garcia for a large cash reward. Although he merely guides Esteban Trueba to Pedro’s location, this can nevertheless be seen as an act of Thomas 2 Candidate Number: 0847-000-0000 malice and greed. Also, Esteban Garcia later becomes involved in the secret police and eventually captures Alba as his prisoner. However, he did not treat her like the rest of the prisoners. He saw her everyday; “at times he appeared to be genuinely moved, personally spoonfeeding soup into her mouth, but the day he plunged her head into a bucket full of excrement until she fainted from disgust, Alba understood that he was not trying to learn Miguel’s true wherabouts but to avenge himself for the injuries that had been inflicted on him from birth, and that nothing she confessed would have any effect on her fate as the private prisoner of Colonel Garcia” (411). He also rapes her and beats her repeatedly during her time in the prison. The strong antagonism of Esteban Garcia’s character is developed by his wordly actions. Unlike protagonists such as Alba and Clara, Esteban Garcia lacks magical realism. It can be observed that during the period of political crisis and during Alba’s time in the prison, magical realism diminishes; however, it comes back strong as the spirit of Clara helps Alba to regain her mental and spiritual strength. Laura Esquivel also uses magical realism in Like Water for Chocolate to enhance the strong protagonism which characterizes its central character, Tita. The foundation for Tita’s protagonism is the pity that her character evokes from the reader. Even from the minute of her birth, “Tita [is] literally washed into this world on a great tide of tears that [spill] over the edge of the table and [flood] across the kitchen floor” (Esquivel 6). During the rest of the novel, it seems as if Tita never really stops crying; “sometimes she would cry for no reason at all, like when Nacha chopped onions… but [Nacha and Tita] didn’t pay them much mind. They made them a source of entertainment, so that during her childhood Tita didn’t distinguish between tears of laughter and tears of sorrow. For her, laughing was a form of crying” (7). Of course, Tita’s tears Thomas 3 Candidate Number: 0847-000-0000 throughout the rest of the novel have significance and emotion to them, but this permanent characterization of Tita also strengthens the conveyed mood of pity. Another instance where one is compelled to feel pity for Tita is, ironically, when she ruins her sister’s wedding. While she cries about the fact that she could never marry, a tear drop falls into the wedding cake, and she fears that it ruined the consistency of the meringue. The cake was fine, however, “the moment [the guests] took their first bites of cake, everyone was flooded with a great wave of longing” (39). It is also because of this spell that Nacha dies, grieving for her long-lost lover from her past. This is a prime example of how Tita’s emotions are reflected literally in her cooking, and how they create spells which have very consequential effects on others. This certainly could never occur in the real world, however this magical realism aids in the symbolic imagery which constitutes the plot of the novel as a whole. The established fact that Tita’s magical cooking greatly affects the lives of others is also especially evident in the character of Gertrudis. After she eats the delicious quail in rose-petal sauce that Tita had prepared from a rose that Pedro had secretly given her, Gertrudis “began to feel an intense heat pulsing through her limbs… her sweat was pink, and smelled like roses, a lovely, strong smell” (52). Her symptoms grew so extreme that she had to run to the shower outside, where she encountered unexpectedly the man of her dreams. Juan “put his arm around her waist, and lifted her onto the horse in front of him, face to face, and carried her away” (56). This is a major turning point in Gertrudis’s life, and she does not return to the ranch for a long period of time. Tita and Pedro are also affected by this enchanted meal. Upon eating, “it was as if a strange alchemical process had dissolved [Tita’s] entire being in the rose petal sauce, in the tender flesh of the quails, in the wine, in every one of the meal’s aromas. That was the way she Thomas 4 Candidate Number: 0847-000-0000 entered Pedro’s body, hot, voluptuous, perfumed, totally sensuous” (52). It is evident that magical realism supports the sublime language which describes this sensation between the two lovers. Esquivel ventures to unveil one of the mysteries of the spiritual subconscious, as she states that “it seemed they had discovered a new system of communication, in which Tita was the transmitter, Pedro the receiver, and poor Gertrudis the medium, the conducting body through which the singular sexual message was passed” (52). It can be observed from this described event that Esquivel incorporates philosophical sublimity into this instance of magical realism, which gives the story a spiritual and mystical charm, as opposed to Allende’s use of magical realism to portray eccentricites as merely conventional daily occurences. In dealing with antagonism in Like Water for Chocolate, Esquivel’s method for the characterization of evil characters differs from that of Allende. Instead of the purposeful lack of magic which Allende demonstrates in these characters, Esquivel’s antagonists still retain their magical realism. For example, even after her death, Mama Elena haunts Tita as a ghost, verbally repremanding her for her undiminishing love for Pedro. Tita stands up against the ghost of Mama Elena and firmly declares that her love will never go away and that she hates and had always hated Mama Elena. These “magic words [make] Mama Elena dissappear forever”, but first the ghost becomes a “little light… [which begins] to spin feverishly” (200). It approaches Pedro, “whirling crazily, with enough violence to make the lamp closest to him explode into a thousand pieces. The oil quickly [spreads] the flames onto Pedro’s face and body” (200). Mama Elena is most clearly identified as an antagonist in her spirit-form, since even as a ghost all she wanted was to haunt Tita and wreak havoc on her and Pedro’s relationship. This instance of magical Thomas 5 Candidate Number: 0847-000-0000 realism is literally involved in the plot and does not have as much of a symbolic effect as in The House of the Spirits. In conclusion, both Allende and Esquivel utilize magical realism in their novels to develop the protagonism of their main characters, although at the same time they convey different ideas. In The House of the Spirits, antagonism is portrayed through the absence of magic, while Esquivel consistently uses magic throughout the plot of Like Water for Chocolate. Moreover, Allende attempts to make the supernatural become natural in her novel, while Esquivel maintains the supernatural in order to create a myth-like anecdote.