Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 1 of 10 Learning Modules

advertisement

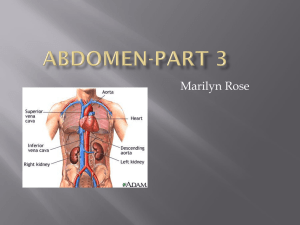

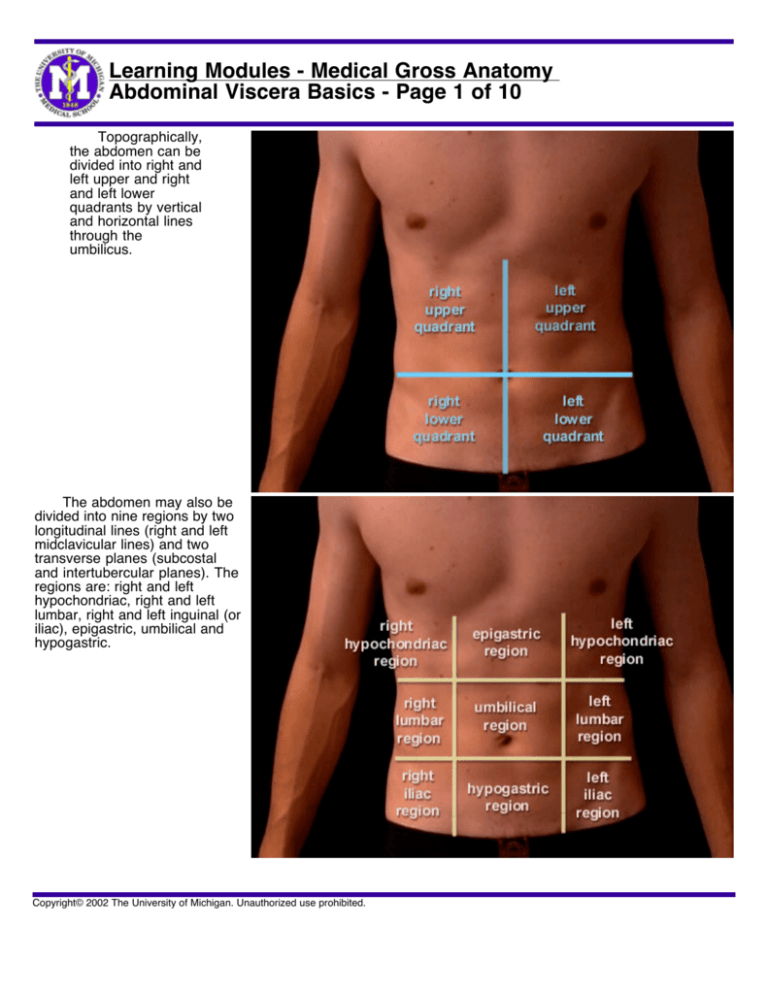

Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 1 of 10 Topographically, the abdomen can be divided into right and left upper and right and left lower quadrants by vertical and horizontal lines through the umbilicus. The abdomen may also be divided into nine regions by two longitudinal lines (right and left midclavicular lines) and two transverse planes (subcostal and intertubercular planes). The regions are: right and left hypochondriac, right and left lumbar, right and left inguinal (or iliac), epigastric, umbilical and hypogastric. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 2 of 10 The abdominal cavity is bounded above by the thoraco-abdominal diaphragm (the respiratory diaphragm or "THE" diaphragm) and below by the pelvic inlet. It is continuous through the pelvic inlet with the pelvic cavity, and the combined space is the abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominal cavity contains the peritoneal cavity, the abdominal organs, and the retroperitoneal space. The peritoneal cavity is a potential space between the parietal peritoneum lining the body wall and visceral peritoneum covering the abdominal organs. The peritoneal cavity is a serous sac, similar to the pleural and pericardial cavities. The retroperitoneal space is behind the peritoneum of the posterior abdominal wall. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 3 of 10 The peritoneal cavity is a potential space between the parietal and visceral layers of the peritoneum and there are no structures within it. The layer lining the abdominal wall, the pelvic wall and pelvic viscera, and the inferior surface of the diaphragm is the parietal peritoneum and the layer lining the surface of the organs is called the visceral peritoneum. Just as in the pleural and pericardial cavities, the peritoneal cavity contains a film of serous fluid that lubricates the peritoneal surfaces and allows free movement of the viscera. As with the pleural and pericardial cavities, the peritoneal cavity surrounds, but does not contain, most of the abdominal organs. Most, but not all, of the organs associated with the GI tract are suspended "within" the peritoneal cavity by connections to the posterior abdominal wall called mesenteries. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 4 of 10 Before looking at the development of the gut, let's consider the basic terminology of the abdominal viscera. The digestive tract begins at the oral cavity, which opens posteriorly into the pharynx, the common food/air tube leading to both larynx and esophagus. The esophagus passes through the lower neck, through the chest, and then pierces the diaphragm at the esophageal hiatus to empty into the stomach. The stomach empties into the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. The head of the pancreas lies in the G-shape of the duodenum and it drains its digestive juices into the duodenum. The liver lies above and to the right of the stomach. The bile duct, which drains the liver, also drains into the duodenum. The gallbladder is a resevoir in the biliary tract. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 5 of 10 The spleen is not an organ of the digestive tract, but it is an abdominal organ. It lies beneath the diaphragm to the left of the pancreas, and mostly posterior to the stomach. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 6 of 10 The small intestine comprises the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum, the first and shortest part, empties into the jejunum at the duodenojejunal junction. The jejunum coils for approximately 8 feet before becoming (by gradual transition) the ileum. The ileum then coils for another 12 feet, approximately, before emptying into the large intestine. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 7 of 10 The large intestine or large bowel comprises in order the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. The cecum receives the contents of the ileum at the ileocecal junction, and the vermiform appendix is attached to the cecum posteroinferiorly. The ascending colon bends to the left at the hepatic or right colic flexure to become the transverse colon. The transverse colon bends down at the left colic or splenic flexure to become the descending colon. The descending colon becomes the S-shaped sigmoid colon to pass over the pelvic brim into the pelvis. The sigmoid colon straightens out as the rectum (which means straight), and rectum ends as the anal canal. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 8 of 10 Mesenteries are doublelayer sheets of peritoneum that suspend most of the gut and associated structures from the posterior body wall and provide pathways for blood vessels and nerves to the viscera, which travel between the two layers. The mesenteries are named according to their associated organ. For instance, the transverse mesocolon suspends the transverse colon from the posterior abdominal wall, the sigmoid mesocolon suspends the sigmoid colon, and "THE MESENTERY" suspends the small intestine. Organs that have a mesentery are called intraperitoneal. Organs without a mesentery are called retroperitoneal. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 9 of 10 Intraperitoneal organs are peritoneal organs that have an associated mesentery, such as the stomach, small intestine (jejunum and ileum), transverse and sigmoid colon, liver, and gallbladder. Retroperitoneal organs do not have a mesentery and are associated with the posterior body wall. Retroperitoneal organs are subdivided into two categories: primarily retroperitoneal and secondarily retroperitoneal. Primarily retroperitoneal organs were present posterior to the peritoneal cavity in the embryo, such as the aorta, inferior vena cava, ureters, kidneys, and suprarenal glands. Secondarily retroperitoneal organs become fused to the posterior abdominal wall during development. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited. Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy Abdominal Viscera Basics - Page 10 of 10 Secondarily retroperitoneal organs once had a mesentery and lost it during development. This happens to certain gut structures during the return of the intestines into the abdominal cavity (discussed later). These organs include the pancreas, duodenum, ascending and descending colons, which are associated with fusion fascia adhering them to the posterior abdominal wall. In the accompanying movie of a cross-section of an embryo, the kidneys (dark purple) are primarily retroperitoneal in the retroperitoneal space (yellow area). The ascending and descending colon develop, suspended within the peritoneal cavity (white area) by a mesentery, and become secondarily retroperitoneal during development. As the colon fuses to the posterior abdominal wall, the peritoneum is lost, and all that remains is an avascular plane, the "fusion fascia" (purple dotted lines) shown at the end of the movie. Copyright© 2002 The University of Michigan. Unauthorized use prohibited.