Culture, Culture Learning and New Technologies

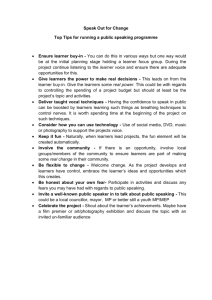

advertisement