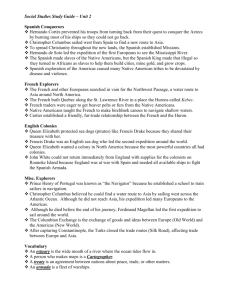

America's History-Chapter 1 The Native American Experience The

advertisement