“The experience you want is in the process of getting it…”

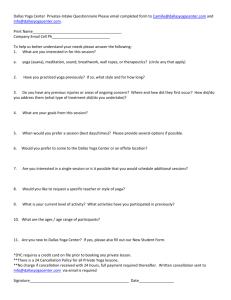

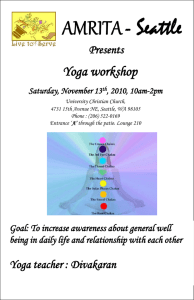

advertisement