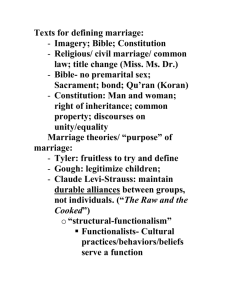

Economic Incentives and Family Formation

advertisement