FINA 351 – Managerial Finance, Chapter 13, Capital Structure

advertisement

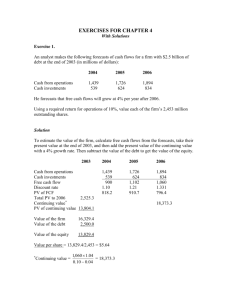

FINA 351 – Managerial Finance, Chapter 13, Capital Structure, Notes 1. What is Capital Structure (CS)? It is the mix of debt and equity on the balance sheet. The basic capital structure question is: How much debt is right for this company? Contrary to what your momma may have taught you, according to the so-called finance experts too little debt may be just as costly as too much debt, because debt financing is usually the cheapest source. This is why it is often said that debt is a two-edged sword: too much is bad but so is too little. 2. Why is CS important? It directly impacts the cost of capital and therefore directly affects the value and profitability of the company. For example, at one time Hershey Foods determined that its cost of capital was 13%, significantly more than the cost of capital of its competitors, which put Hershey at a significant competitive disadvantage. It might have even put Hershey out of business if steps were not taken to address this issue. 3. Can a company choose its CS? If so, how? Yes, within reasonable limits. If it wants more equity, the company can issue stock and pay off debt. If it wants more debt, it can borrow and with the proceeds buy back stock. The last step was what Hershey Foods did to raise its debt/equity ratio and thereby reduce its cost of capital from 13% to 11%. Because of aggressive cost of capital management, Hershey was able to reduce its WACC from being one of the highest in its industry to being one of the lowest (see graph below). 4. Who were M&M?. Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani (both deceased) were finance/econ professors at U. of Chicago and MIT, respectively. They won a Nobel Prize in Economics for their work on capital structure. Merton was once asked by a news journalist to summarize the work he did which won a Nobel Prize. His answer was too long and complicated for an audience accustomed to 10-second sound bites. Finally, he suggested a simple analogy: if you cut a pizza into smaller pieces, you’ll have more pieces but not more pizza. In other words, if you ignore income tax and financial distress costs, your firm should be worth the same whether it was financed with all debt or all equity. The news camera crew folded up their cameras and said they’d get back to him. Merton decided he had somehow missed his chance to package economic wisdom in 10-second sound-bites. M&M Theorem and Pizza: After the ball game, the pizza man asked Yogi Berra if the pizza should be cut into four slices as usual, and Yogi replied: “No, cut it into eight; I’m hungry tonight.” The moral of the story? More pieces do not mean more pizza. The main point of the M&M propositions were that if you ignored taxes and financial distress costs, whether you get your L/T financing from debt or equity should not matter. 5. Is there an optimum CS? If so, what about M&M’s Proposition Case I? As illustrated, Case I shows that the mix of debt/equity doesn’t matter if taxes and financial stress costs are ignored (the size of a pizza doesn’t depend on the number of pieces). But Case II and Case III show that when taxes and financial distress (bankruptcy) costs are considered, the value of firm most certainly peaks at an optimum point. Every CFO has a target CS for the optimum level that minimizes cost of capital. An executive at AT&T, for example, was asked by a reporter what its optimum level of debt was. The executive answered without hesitation. So it is obvious that AT&T had already put a lot of thought and study into this question. 6. Who determines the optimal CS and how? Management and the board are charged with these important decisions. How they decide differs from firm to firm but in general they use: (1) internal studies and investment bankers to help crunch the WACC formulas, (2) follow the industry average, and/or (3) use their intuition. 7. Is the CS of companies similar within an industry? Yes. Companies in uncertain or cyclical industries (often with higher betas) need the flexibility that low-debt brings. For example, drug companies might make it big with one product, but they never know when if the next drug will be approved and how it will sell. Companies in more stable industries (with lower betas) are in a better position to carry higher debt, such as cable television. Industries that require a lot of heavy industrial equipment or infrastructure typically need more L/T financing, such as airlines or electrical utilities. On the other hand, industries with little infrastructure usually need little debt, such as computer software companies. 8. What is the Overall Pattern of CS in the U.S.? Debt/Total Assets is about 60% based on book values, but closer to 30% based on market values. Recently, long-term financing has come from debt more often than equity, with equity financing actually being negative (more stock repurchased than issued) in some years. However, IPOs have been picking up lately. Overall, companies in the U.S. have not used debt financing as much as they could have – there appears to be excess tax shield from debt financing that could be utilized if desired. 9. At what point is the optimum CS? The optimum CS is the where the mix between debt and equity (weights) causes the cost of capital to be at its lowest point. 10. What are the advantages and disadvantages of more debt? Advantages: (1) Debt is cheaper than equity financing because interest is tax deductible (dividends are not) and because it is less risky to investors than equity (i.e. debt investments carry a guaranty of interest and principal; equity investments carry no such guarantee) (2) Higher debt brings greater incentive for efficiency – people tend to fight harder with their backs up against a wall, out of a sense of desperation if nothing else. (3) Higher leverage brings a greater return on equity to owners. This is one of the main points in this chapter. Here’s a simple example. Suppose the balance sheet for your business had assets of $100k, liabilities of $60k, and equity of $40k. If your business made a profit of $20k, you would have a return on equity of 50% (20k/40k). Supposed instead that your balance sheet was leveraged with more debt (e.g. assets of $100k, liabilities of $80k, and equity of $20k). Now a $20k profit creates a return on equity of 100% ($20k/$20k). Notice that debt leverages your return on equity, in the sense that the more of other people’s money you use (debt), the higher the return on your equity. You’re using other people’s money as a lever to maximize return on equity. This is the main reason that many financial firms leading up the financial crisis of 2008 were so highly leveraged. For example, Bear Stearns had $33 of debt for every $1 of equity (i.e. there was only 3 cents of equity for every dollar of assets). Such high leverage means there is very little capital to absorb losses, which is why these firms failed. Disadvantages: (1) financial distress/bankruptcy costs are very expensive (time, stress, morale, etc.). (2) when debt gets too high, the cost required for additional debt gets prohibitive (e.g. loan shark interest rates are always in the double digits). 11. What are two forms of bankruptcy? Chapter 7: the company is worth more dead than alive – kill the company and sell the assets. But creditors are often lucky to get pennies on the dollar and owners lose everything. Chapter 11: the company is worth more alive than dead. The creditors feel there’s a better chance of getting their money back by altering the terms of the loan, making concessions, and allowing the company to survive. Many times companies will recover very quickly (e.g., 7Eleven was in Ch. 11 only for a few months.) Note: there are other forms of bankruptcy as well, such as Chapters 9, 12 & 13. Ch. 9 is for municipalities, such as Detroit, MI; Jefferson County, AL; Harrisburg, PA; Vallejo, CA; Desert Hot Springs, CA; or Orange County, CA. Ch. 12 & 13 are similar to Ch. 11 but for farmers (Ch. 12) or other private individuals (Ch. 13) with steady income and smaller amounts of debt. 12. In bankruptcy, in what order are creditors paid off? Negotiation usually occurs which means that the order below is not always followed. But usually the claims are paid in the following order: 1. Secured creditors (to the extent that collateral value) 2. Administrative expenses associated with bankruptcy (accountants/lawyers, courts costs, etc.) 3. Employee compensation owed 4. Consumer claims 5. Government claims 6. Unsecured creditors (e.g. debenture bonds) 7. Preferred stockholders 8. Common stockholders 13. What is an LBO and how does it affect CS? A leveraged buyout occurs when somebody (management or an outsider) use the proceeds from debt (usually junk bonds) to buy the stock at a premium from existing owners. This buyout of the owners adds more debt to the balance sheet. If debt levels were low, this could theoretically bring the debt level up to the optimum point. The resulting increase in the value of the firm will offset the cost of the premium offered. But in the past, LBOs have often added too much debt to the balance sheet, causing the value of firms to eventually decrease (this has occurred about 25% of the time). An example is the bankruptcy of Federated Dept. Stores (Bloomingdale’s, Macy’s, Bon-Marche, etc.) when Robert Campeau saddled the company with excessive debt in an LBO. 14. How can Ch. 13 be summarized? Here’s a simplified picture (summary) of Ch. 13. In a nutshell, it says that a firm with no debt is not taking advantage of the tax deduction that comes with debt financing. As debt is added, the tax shield causes the WACC to lower and the value of the firm to increase – but only up to a point, called the optimal capital structure (OCS), beyond which increased debt levels actually cause the WACC to increase and the value of the firm to drop, due to financial distress costs. Level of Debt