Tufts University School of Dental Medicine

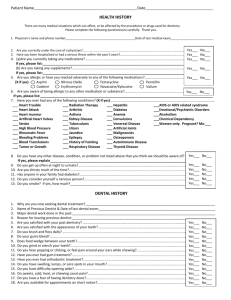

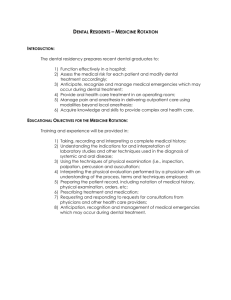

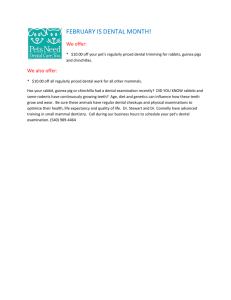

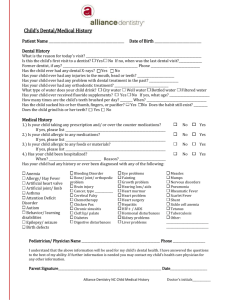

advertisement