OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS

advertisement

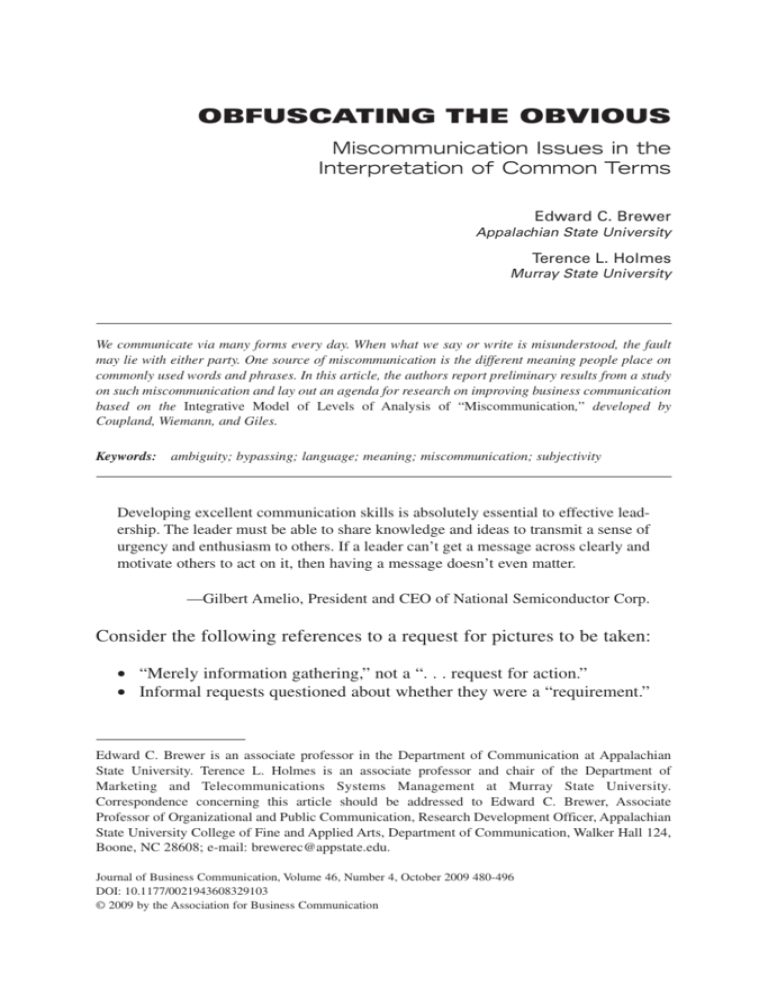

OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS Miscommunication Issues in the Interpretation of Common Terms Edward C. Brewer Appalachian State University Terence L. Holmes Murray State University We communicate via many forms every day. When what we say or write is misunderstood, the fault may lie with either party. One source of miscommunication is the different meaning people place on commonly used words and phrases. In this article, the authors report preliminary results from a study on such miscommunication and lay out an agenda for research on improving business communication based on the Integrative Model of Levels of Analysis of “Miscommunication,” developed by Coupland, Wiemann, and Giles. Keywords: ambiguity; bypassing; language; meaning; miscommunication; subjectivity Developing excellent communication skills is absolutely essential to effective leadership. The leader must be able to share knowledge and ideas to transmit a sense of urgency and enthusiasm to others. If a leader can’t get a message across clearly and motivate others to act on it, then having a message doesn’t even matter. —Gilbert Amelio, President and CEO of National Semiconductor Corp. Consider the following references to a request for pictures to be taken: • “Merely information gathering,” not a “. . . request for action.” • Informal requests questioned about whether they were a “requirement.” Edward C. Brewer is an associate professor in the Department of Communication at Appalachian State University. Terence L. Holmes is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Marketing and Telecommunications Systems Management at Murray State University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Edward C. Brewer, Associate Professor of Organizational and Public Communication, Research Development Officer, Appalachian State University College of Fine and Applied Arts, Department of Communication, Walker Hall 124, Boone, NC 28608; e-mail: brewerec@appstate.edu. Journal of Business Communication, Volume 46, Number 4, October 2009 480-496 DOI: 10.1177/0021943608329103 © 2009 by the Association for Business Communication Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 481 • The same informal requests being “effectively terminated” since they were not a “requirement,” and senior managers who were unaware of the informal requests telling their general manager that they knew of no “official” requests. • Those requesting the pictures were asked if they had a “mandatory need” for the photos. They didn’t know what the term mandatory need meant, so they didn’t pursue it further. The scenario summarized above might make for an interesting sidebar to a discussion of communication problems if not for the subject of the requested photos. In January 2003, the team of experts investigating the extent of possible damage to the Space Shuttle Columbia made an informal request for Defense Department photographs to try to determine how much damage the shuttle sustained to one wing upon liftoff for its ill-fated mission. The board that investigated the resulting disaster and loss of seven astronauts issued the quotes above in its report. The question that will always be in people’s minds is, “Could NASA have done something to detect the damage and either repair it or mount a rescue of some sort?” (Stein, 2003). Although the consequences of poor communication are seldom as severe as those faced by the NASA mission team leaders, we all encounter substandard outcomes stemming from miscommunication. It is an issue in all facets of life. We take much of our communication for granted. Mortensen (1997) reminds us that “it is virtually impossible to come into direct contact with another person without making personal assumptions” (p. 27). Organizations are, of course, interested in achieving accurate communication and minimizing inadvertent miscommunication in support of internal and external communication of business plans and actions. Businesses desire employees to learn proper communication tactics and how to avoid misunderstandings that can lead to dissatisfaction among organizational colleagues and between the organization and its customers and other stakeholders. SUBJECTIVE PROBABILITY In this article, we examine miscommunication issues that occur as a result of commonly used terms that relate to the likelihood that something will occur (such as always, never, probably, usually, and often) and when something will occur (such as ASAP, soon, today, tomorrow, and right away). The term subjective probability is commonly used to describe the 482 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION words dealing with the likelihood an event will occur. Researchers from several different disciplines have noted how people consider such probabilities in their decision making. For example, Bassett and Lumsdaine (2001) studied accuracy in relation to subjective assessments in health and retirement decisions, while Kardes et al. (2001) examined consumer belief systems as stated through subjective probability calculations. Most of this and other research concerning subjective probability has focused on investigating specific belief systems. In this article, we focus on subjective probability and its role in the effectiveness of the communication process. Understanding the implications of the use of such terms can help in formulating better training to improve communication effectiveness at all levels of the business environment and in organizations of all types. The linear model of communication introduced over half a century ago by Shannon and Weaver (1949) introduced the concept of “noise.” Communication models, of course, have become much more dynamic to represent the transactional nature of communication. As the understanding of noise has expanded, vague words (such as soon, ASAP, probably, often, etc.) can be identified as part of this noise that results in a loss of information during the flow of communication from source to destination. Recent research has examined perception and miscommunication in the construction industry (English, 2002) and on performance evaluations that could ultimately affect productivity (Milliman, Taylor, & Czaplewski, 2002). Others have noted communication difficulties as a factor in collective bargaining (Knowles, 1958), as well as the previously mentioned accuracy issues (Bassett & Lumsdaine, 2001) and the subjective nature of consumer beliefs (Kardes et al., 2001). As the subjective areas of these studies reflect, the communication problem is both persistent and universal and can result in troubling consequences, such as lower productivity, poor motivation, loss of customers, and other unfavorable outcomes. In addition to subjective probability, the understanding of time can be an important contributor to miscommunication. How a message sender makes sense of or understands time may be quite different from the message recipient’s understanding of the same concept. Butler (1995) examined time as a variable in organizational analysis. He presented a conceptual framework that included “the notion that time, as we experience it in the present, can only have meaning in relation to our understanding of the past and our vision of the future” (p. 946). Butler pointed out that “all organizational processes have a time dimension” (p. 947). Thus, the understanding of both probability issues Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 483 and time issues regarding miscommunication can have a major impact on the effectiveness of individual and organizational communication. As the subjective areas of these studies reflect, the communication problem is both persistent and universal and can result in troubling consequences, such as lower productivity, poor motivation, loss of customers, and other unfavorable outcomes. COMBATING AMBIGUITY Interlocutors tend to need a sense of clarity. Haywood, Pickering, and Branigan (2005) found that “speakers can be sensitive to potential ambiguities, and that they try explicitly to disambiguate their utterances when the visual context affords the opportunity for miscommunication” (p. 366). While the visual aspect could take us to a whole new realm, the idea that speakers can be sensitive to the ambiguous nature of language is an important consideration for organizational communication at all levels. Misunderstanding occurs when difficulties with understanding or comprehension are not revealed interactionally (Olsina, 2002). Linguistic scholars have also studied equivocation in communication (Janicki, 2002). Janicki (2002) concludes, “Both the professional linguist and the layperson appear to believe that much of the use of difficult/incomprehensible language is an unnecessary hindrance to communication, no matter what the reasons for that use may be” (p. 212). Clearly, ethical problems could arise from the misuse of ambiguous communication, especially if it is intentionally used to deceive the other party. An ethical discussion of miscommunication could also take us in a whole new direction that we do not pursue in this study. However, we will mention here that ambiguity is not necessarily bad. For instance, Eisenberg (1984) suggests that “particularly in turbulent environments, ambiguous communication is not a kind of fudging, but rather a rational method used by communicators to orient toward multiple goals” (pp. 238-239). As the interlocutors process equivocal language, meaning becomes an issue. Turner and Krizek (2006) raise this issue: 484 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION Assuming that meanings are understood in relation to other meanings begs the question, “Which meanings do we use as context?” This question is consistent with the hermeneutic tradition’s concepts of the hermeneutic circle, wherein the part can only be understood in relation to the whole and the whole in relation to its parts. . . . The hermeneutic circle does not provide an answer; rather, it validates the need to continually ask the question and move through repeating iterations of interpretation at multiple contextual levels. (p. 138) Relying on only one perspective can be dangerous when making sense of a situation or communication process. Larson (2003) uses a fire that occurred in Colorado in 1994 (named by state officials as the “South Canyon Fire”) as a case study to examine the concept of organizational sense making and discusses the “particle” (product or customer) worldview as a distinct way of thinking and seeing from the “activity” (organizational) worldview. In discussing practical implications, Larson (2003) states, “Over-reliance on a particle perspective neglects the specialized activities vital to organizations” (p. 11). The South Canyon Fire tragedy, during which 14 firefighters died, demonstrated a need for understanding both perspectives. Relying on only one perspective can be problematic when trying to make sense of meaning within the context of a communication event. Applying Larson’s discussion of “worldview” to the understanding of context in an organizational communication event thus illustrates the need for common understanding. Thus, the understanding of both probability issues and time issues regarding miscommunication can have a major impact on the effectiveness of individual and organizational communication. Quite obviously, there are implications for training in business and interpersonal relationships. Gonzalez et al. (2004) call for incorporating more knowledge and skills relating to communication, teamwork, and multifunctional teams. Clarifying meaning in common terms seems like an obvious way to increase shared meaning in both business and interpersonal settings, but these terms are so common that usage is often taken for granted, and context is not always fully considered. Even researchers seeking to examine where or what the communication problems might be find Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 485 it difficult to accurately estimate the source or the extent of the problem area. Past research shows that alternative formats for measuring miscomprehension can result in different estimates of such miscomprehension (Gates & Hoyer, 1986). For example, subjective probability literature includes empirical studies that employ many different data collection methods, from open-ended responses such as those we used in the study described later in this article, to providing a scale from 0 (absolutely no chance) to 10 (definitely will occur), and so on (Bassett & Lumsdaine, 2001; Budescu & Karelitz 2003; Kardes et al., 2001). Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact nature of miscommunication, we believe our research begins to move us toward a better understanding of common problem areas and thus toward increased understanding of ways to achieve shared meaning. RESEARCH PURPOSE Previous work on miscommunication has focused on nonachievement of shared meaning. From studies based on pedagogical issues such as classroom exercises (Holmes & Brewer, 2006) and cases (Brewer & Holmes, 2006), to dramaturgical issues (Rosile, 2003), to customer satisfaction analysis (Turner & Krizek, 2006), the common thread is the desire to improve interpersonal and/or organizational communication. The current article represents a transition from pedagogical aspects of overcoming miscommunication to more organizational concerns of improving effectiveness and efficiency in the workplace. Clarifying meaning in common terms seems like an obvious way to increase shared meaning in both business and interpersonal settings, but these terms are so common that usage is often taken for granted, and context is not always fully considered. To begin addressing this transition, we adapt a framework introduced by Coupland, Wiemann, and Giles (1991; see Table 1). Their Integrative 486 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION Table 1. Integrative Model of Levels of Analysis of Miscommunication Level Characteristics 1 2 3 4 5 6 Problem Status Awareness Level Meaning transfer Unrecognized inherently flawed Minor Possibly, not misunderstandings necessarily or misreadings routine; recognized to be expected Presumed Attributed to personal individual deficiencies lack of skill or ill will Goal referenced Recognized as (control, affiliation, failure in identity, goal instrumentality) attainment Group/cultural norm Mapped onto differences in social language and identities communication; and group predisposing memberships misunderstandings Ideological framings of talk; sociocultural power imbalances Participants see status quo only Repairability Participants Not relevant are unaware For participants, Relevant at low; at local local level only level for researchers For participants, Deficiencies moderate; can be directed fixed (e.g., to other training) Participants see Ongoing behavior’s aspect with strategic relationship implications implications Moderate; group Acculturation; identities taken out-group for granted; accommodation; differences seen sociocultural as natural learning reflections of group statuses Participants Only through unaware but critical analysis researchers are and resulting hyperaware social change (ideology driven) Source: Adapted from Coupland, Wiemann, and Giles (1991). Model of Levels of Analysis of “Miscommunication” (Coupland et al., 1991, pp. 12-13) is instructive on several fronts. The framework these authors present describes each level of miscommunication along (a) problem status (i.e., attributions as to the reason for this level of miscommunication), (b) awareness (i.e., do the participants in a communication setting, and/or researchers studying communication within that setting, recognize that miscommunication is a problem?), and (c) repairability (i.e., can the miscommunication that is the root cause of a set of problems be fixed?). The six levels of “miscommunication” help researchers in recognizing that not all such problems in communicating are equal in their importance and social significance. Thus, each of the six levels has characteristics that involve different problems, awareness of problems, and repairability. Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 487 Much of the research we discuss above has taken place within the first four levels of the Coupland et al. (1991) framework. Our previous work (Holmes & Brewer, 2006; Brewer & Holmes, 2006) discovered that participants did not know that discrepancies in interpretations of meaning were commonplace (consistent with Level 1 in the framework). These same works also involve Levels 2 and 3 of the model (i.e., a focus on interpersonal issues and opportunities for training and development regarding communication skills), with additional implications for Level 4 (the pervasiveness of such miscommunication and how to lower its occurrence or even avoid it altogether). The first four levels of the framework are important for business communication because the awareness, improvement, and relationship-building implications can guide managers in creating and maintaining a better workplace culture, where wasted time and hurt feelings are mitigated. We address the last two levels of the framework as well. These higher levels regard group and/or cultural differences (Level 5) and issues of power, ideology, and social change (Level 6). Research Questions We pose three research questions. Research Question 1: Does common context lead to less ambiguity? In conversations with participants after running our communication exercise, we found that subjects believed a common context would prevent miscommunication (Holmes & Brewer, 2006). This idea is based on two people talking and one using common terms. Given that their conversation is centered on the same subject, many felt that the result should be a lower level of ambiguity. Before this feedback, we had collected data based on individual subjects’ own interpretation of each term, with no attempt at defining a context that everyone then addressed. In this exploratory research, we collected data to begin investigating whether a common context will lead to less ambiguity. Research Question 2: Is there a difference in variability between common terms for time and common terms for probability? The common terms used in previous communication research are from two domains—probability and time. The terms used in this study stem from a communication training program (1987 Life Office Management Association Telephone Training Program, Atlanta, Georgia), which we have drawn on previously (Holmes & Brewer, 2006), and are meant to be representative of everyday language that is substituted for actual lengths of time and actual probabilities. Our 488 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION research is aimed at improving communication (by lessening miscommunication) in organizational settings. While the actual terms in both sets have shown the type of variability that could lead to misunderstanding, research has not previously been done to try to determine whether one or the other—that is, probability or time—is a bigger problem area. We hope our data will help begin the process of determining whether such a difference exists. Research Question 3: Is there a difference in variability for the terms based on demographic differences among the participants? In conducting the communication exercise with hundreds of participants over several years, we have noted during the debriefing period that many people base their interpretation of each term’s meaning on work experience. For those participants who have had little or no such experience, we have heard debates between individuals and/or groups based on their cultural upbringing, age, and gender. The Coupland et al. (1991) framework is supportive of our rationale for Research Question 3 as well, with such effects corresponding to the characteristics described for Levels 3, 4, and 5 of that model. In this exploratory research, we also wanted to begin investigating whether such anecdotal evidence is reflected in the data collected. If there are such differences, managers could benefit from knowing more about how miscommunication problems might differ based on the makeup of their staff (e.g., number of men and women, number of international and domestic workers, etc.) and/or the setting within which they manage (e.g., young, entry-level workers vs. a stable group of experienced staff; high vs. low turnover; etc.). Thus, finding out whether such factors have a global effect at all is an important first step. METHOD We collected data from a convenience sample of 345 graduate and undergraduate students in communication and marketing classes at a small southeastern university. For the initial phase of our research, we used a communication exercise, conducted as part of classroom activities. Open-ended responses were collected, as the terms for first probability (always, never, probably, usually, often) and then time (ASAP, soon, today, tomorrow, right away) were called out and placed on an overhead transparency or other display. Students were asked to record their own Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 489 interpretation of the meaning of each term. To clarify the type of response expected, we asked the subjects to simply record the probability (a number between 0 and 100) and time (number representing days, hours, minutes, etc.) that they would apply if they used the word always and so on for the five probability and five time-based terms. To investigate context effects (Research Question 1), we designed a communication scenario intended to provide the common context noted as a possible rationale for better communication of probability and time (see Appendix). After designing the scenario, we used it as the basis for data collection in the second phase of our research. We thus collected data within three groups for addressing our research questions. These were designated as follows: Group 1, open-ended response (no scenario provided, n = 160); Group 2, scenario-based response from manager’s perspective (n = 94); and Group 3, scenario-based response from customer’s perspective (n = 91). In addition to the participants’ responses to the probability and time terms, we collected basic demographic data to enable a first look at the possible differences referenced in the third research question. Participants recorded the following information: years of full-time work experience, whether they were a U.S. citizen, age, and gender. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION The main purpose of our research is to investigate, illustrate, and recommend methods for overcoming miscommunication problems. In this exploratory effort to begin pursuing such results, we want to show how easily miscommunication can occur and just as easily be corrected. Thus, we concentrate on some descriptive statistics for the three groups on each of the 10 terms used in the study (see Table 2). In addition, to answer our research questions exploring whether there were various group and/or individual differences across the terms, we conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for each set of terms. The first such analysis showed no difference among the three groups on the set of five terms dealing with probability, while the second MANOVA, for the time-based terms, did show an overall difference. However, in the latter case, only two terms were contributing to this overall difference (today and right away), and these were significant only at the .10 level (.08 and .086, respectively). Thus, while there was a small statistical difference between open-ended and scenario-based responses 490 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION Table 2. Term Always Never Probably Usually Often ASAP Soon Today Tomorrow Right away Mean and Standard Deviation by Group Groupa Mb SD 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 91.15 90.68 90.62 13.80 8.29 12.69 61.33 56.42 61.42 69.54 67.94 64.62 63.38 62.17 59.08 18.65 14.62 14.58 140.61 46.09 42.74 11.96 9.14 10.79 31.29 31.71 34.76 3.91 9.47 8.15 15.33 15.31 13.70 25.24 15.38 25.34 17.24 17.74 18.48 15.91 17.39 18.46 17.23 21.76 19.93 72.07 30.06 27.41 848.02 44.74 45.30 8.23 7.95 8.99 12.41 14.73 20.26 17.69 20.14 15.90 a. Group 1, n = 160; Group 2, n = 94; Group 3, n = 91. b. The mean is presented in percentages for the first five terms and in hours for the last five terms. for one set of terms, the practical meaning is that the common context did not lead to much closer interpretations of either probability or time common terms. The unit of analysis is an important consideration in the context of our research on miscommunication. From a practical significance standpoint, when looking at the range of the data for the common terms for probability, one can see that vast differences could occur in the percentages each Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 491 party to a conversation intends. Imagine that you are a new supervisor and your own definitions of the common terms we used in our research are in line with the reported means. In telling a subordinate that he will probably obtain a raise based on his performance, you thus mean there is about a 60% chance of this outcome, while the subordinate who is only a couple of standard deviations away considers this statement a promise of a near certainty. Likewise, for the time-based terms, the reported units are hours. For this example of the practical significance of our preliminary findings, let’s look at the standard deviation for right away, which, from Table 2, we see ranges from about 16 to 20 hours. If you use this term in asking a colleague for an update in preparation for meeting an important client, there could be a large difference in meaning between you and him—perhaps as much as the entire business day! With regard to our first research question (Does common context lead to less ambiguity?), the common context—based on the above analysis of the responses—does not make a practical difference in the range of responses to the terms’ meaning. Thus, it appears that clarifying the meaning of ambiguous terms is important for better understanding even if the participants think they’re discussing the same subject. Thus, it appears that clarifying the meaning of ambiguous terms is important for better understanding even if the participants think they’re discussing the same subject. Regarding Research Question 2 (Is there a difference in variability between common terms for time and common terms for probability?), the preliminary data suggest that the more problematic terms are those dealing with time (Table 2). That is, with the exception of today, the time terms have much larger standard deviations than do the terms for probability. For example, the two probability terms that suggest a particular answer (based on their dictionary definitions) are always (100%) and never (0%). However, in our experience, participants do not respond with 100% and 0%, respectively. Answers are in the 90% range for always and 492 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION around 10% for never. The three other probability terms are strikingly similar to each other, with responses ranging from about 60% to 70%. Turning to the time-based terms, we find much more potential for miscommunication and conflict. The unit of analysis for these terms is hours. Looking at ASAP and right away, we can see that although most definitions of these two terms connote a sense of immediacy, one standard deviation for ASAP ranges from just over 27 hours to 72 hours. In other words, 1 to 3 days of difference! The same is true for right away. While the means for the three groups are the smallest (again, measured in hours) of the time-based terms, one standard deviation for right away ranges from 16 to 20 hours. Thus, even with these two more closely matched terms (relative to the other three time-based terms: soon, today, and tomorrow), there is a great deal of potential for miscommunication. For example, in asking a colleague for an important document you want later that same day, suppose you tell him you “need it ASAP.” Just before leaving for a meeting with a valued client, you drop by his office to pick it up and discover he is gone for the day, leaving you a note that he knows you need the report “ASAP” and that he’ll have it to you the following morning. As the data show, this miscommunication is not surprising if you actually meant “in a few hours” or “by three o’clock today” but your colleague’s idea of ASAP is 16 hours or more! Research Question 3 (Is there a difference in variability for the terms based on demographic differences among the participants? ) was posed to focus on factors likely to be associated with miscommunication, based on both our observations in conducting the exercise and in obtaining feedback during debriefing of participants. However, a MANOVA showed no significant difference among the groups based on the four variables for which we collected data (gender, number of years of work experience, age, and U.S. citizen/non-U.S. citizen). Still, as with the standard deviations among the three groups reported in Table 2, there are large ranges of responses for all of the common terms in both the probability and the time categories. For example, in Table 2, we report the mean for the term soon for Group 1 as 140.61 hours with a standard deviation of 848.02. These statistics include one outlier—specifically, soon reported as meaning 1 year. We included that number in our analysis, however, because during debriefing, the participant who used that amount of time stated that in his experience, soon had no real meaning and might as well be a year. In light of this, we reran the analysis for Group 1 (open-ended responses) without that participant’s response; the mean dropped to 64.24 hours with a standard deviation of 188.29. Even without such a large outlier, then, soon can lead to a wide range of meanings for time. Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 493 RECOMMENDATIONS To complement the workplace examples we provided within the discussion above, we next offer several general suggestions that can help avoid ambiguities that lead to miscommunication. First, communicators can train themselves not to use the probability terms or, at a minimum, to conjoin them with the actual percentage (or ranges) they have in mind. Similarly, for the time-based terms, communicators should use actual dates and times instead of (or accompanying) these and other shorthand terms for time. Gaining better self-awareness of the language can help communicators monitor whether they might slip into the use of the probability and/or time-based terms. In so doing, they can catch themselves, clarify their meaning immediately, and thus, avoid unpleasant effects of miscommunication. In monitoring language used in communication, another recommendation is to be aware that some people use these terms purposefully. Whether or not counterparts are being guileful, careful listening can help people detect such ambiguous language. The immediate response should be to ask questions about what they mean—the key finding in our work is that you should not assume others have the same definitions for words and terms as you do. Incredulity (“How could he possibly have meant that?”) or anger (“I’m as upset with you as the client was with me when I told her I didn’t have the report!”) is useless. To improve outcomes for the long term, communicators must be aware of the sources of miscommunication, better manage their words, and be alert when hearing or reading ambiguous language. Our research in relation to the Coupland et al. (1991) framework is an important guide here. Across the six levels of the framework, avoiding ambiguity and detecting and challenging others’ ambiguity can help communicators increase awareness of the problem and arrive at corrective action (repairs). LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH We are in the preliminary stages of the research agenda and have thus far used student subjects. We are taking an element of miscommunication repair (column 4 of the Coupland et al., 1991, framework) and building our research out to include the root causes of miscommunication and the relevance of such issues for managers. Those wanting to investigate miscommunication and remedies for it should consider other subjects and scenarios. For example, field experiments in workplace settings, in-depth interviews, and case studies are possible future avenues. 494 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION Another term often used to indicate these misunderstandings or different definitions for the same term is bypassing (Folsom, 2006; Palmeri, 2004; Sullivan, Kameda, & Nobu, 1991). Context and culture play a critical role in interaction and combating ambiguity. Sullivan and Kameda (1982), for instance, cite an example of a misunderstanding because an American worker interpreted the phrase “more than 25 units” to mean 26 or more units, but the Japanese manager interpreted the phrase to mean 25 or more units. This cultural difference coincides with Level 5 of the Coupland et al. (1991) model. Researchers investigating the types of miscommunication we explore here might further explore the demographic variables we examined. In addition, given the cynical view of the term soon on the part of one participant, perhaps attitudinal constructs may be introduced in future studies. The common terms we have used thus far are by no means exhaustive of the types of vague language at the heart of miscommunication. Rather, they are a sampling of such terms, based on those used in a training exercise module. We have begun to explore other such terms by collecting subjects’ “favorite” equivocations and encourage other communications researchers to explore other ambiguous terms as well. APPENDIX Communication Exercise Scenario After reading the following paragraph, answer the questions that follow. At 10:00 am on Tuesday, Ann and Jay went to Hometown Bank to apply for a loan for a house they had made an offer on. They needed a $125,000 loan to go with the $50,000 they had saved. Although they told Robert, the loan officer, that they needed to close on Friday, they didn’t tell him about the catch. The seller needed to close on Friday as she was being transferred out of the country. Since Ann and Jay’s offer had been accepted, the seller had received another offer for $165,000 cash. Thus, if Ann and Jay could not close on Friday, the house would close on Monday with the buyer who had cash in hand. Robert assured Ann and Jay, “Loans for people like you who have such a good down payment and decent credit are always approved.” “I often talk with corporate headquarters; in fact,” Robert continued, “We will probably know tomorrow.” Ann said, “I am really excited about the house and want to make sure this goes smoothly.” Robert replied, “We never have any problems in cases like this.” “What about the money?” Jay interjected. “You will get that soon,” Robert said. “Usually, the customer can have the cash right away once they have been approved.” “Will you rush this along for us?” asked Ann. “I’ll do it today,” Robert assured them, “and then I’ll call you ASAP after I have an answer. Ann and Jay left the bank to wait excitedly for Robert’s call. (continued) Brewer, Holmes / OBFUSCATING THE OBVIOUS 495 APPENDIX (continued) After reading the above paragraph, participants were asked to put themselves either in the place of Ann and Jay or in the place of Robert. Imagining themselves under those circumstances, then, in one of those two roles, they were asked to indicate what they would mean if they used the 10 terms below that are found in the scenario. Answer for these words in terms of probability (i.e., between 0% and 100%). Always _____ Never _____ Probably _____ Usually _____ Often _____ Answer for these words in terms of time (i.e., no. of minutes, hours, days, etc.). ASAP _____ Soon _____ Today _____ Tomorrow _____ Right away _____ Note: See Brewer & Holmes, 2006. REFERENCES Bassett, W. F., & Lumsdaine, R. L. (2001). Probability limits. Journal of Human Resources, 36(2), 327-363. Brewer, E. C., & Holmes, T. L. (2006). The loan: A case on communication. In B. Berman & J. R. Evans (Eds.), Great ideas in retailing (10th ed., pp. 68-70). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Budescu, D. V., & Karelitz, T. M. (2003, July 14-17). Interpersonal communication of precise and imprecise subjective probabilities. Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Imprecise Probabilities and Their Applications, University of Lugano, Switzerland. Butler, R. (1995). Time in organizations: Its experience, explanations and effects. Organizational Studies, 16(6), 925-950. Coupland, N., Wiemann, J. M., & Giles, H. (1991). Talk as “problem” and communication as “miscommunication”: An integrative analysis. In N. Coupland, J. M. Wiemann, & H. Giles (Eds.), “Miscommunication” and problematic talk (pp. 1-17). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Eisenberg, E. M. (1984). Ambiguity as strategy in organizational communication. Communication Monographs, 51, 227-242. English, J. (2002). The communication problems experienced by workforce on-site, and their possible solutions. Journal of Constructions Research, 3(2), 311-321. 496 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS COMMUNICATION Folsom, W. D. (2006, April-June). Deciphering business jargon. Business & Economic Review, 11-14. Gates, F. R., & Hoyer, W. D. (1986). Measuring miscomprehension: A comparison of alternative formats. Advances in Consumer Research, 13(1), 143-146. Gonzalez, G. R., Ingram, T. N., LaForge, R. W., & Leigh, T. W. (2004). Social capital: Building an effective learning environment in marketing classes. Marketing Education Review, 14, 1-8. Haywood, S. L., Pickering, M. J., & Branigan, H. P. (2005). Do speakers avoid ambiguities during dialogue? Psychological Science, 16(5), 362-366. Holmes, T. L., & Brewer, E. C. (2006). An experiential classroom exercise to improve communication effectiveness. Retrieved from http://www.marketingpower.com/Community/ ARC/gated/Documents/Teaching/AME/AME_Articles_2006_05_Holmes_Brewer.pdf Janicki, K. (2002). A hindrance to communication: The use of difficult and incomprehensible language. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 12(2), 194-217. Kardes, F. R., Cronley, M. L., Pontes, M. C., & Houghton, D. C. (2001). Down the garden path: The role of conditional inference processes in self-persuasion. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11(3), 159-168. Knowles, W. H. (1958). Noneconomic factors in collective bargaining. Labor Law Journal, 9(9), 698-704. Larson, G. S. (2003). A “worldview” of disaster: Organizational sensemaking in a wildland firefighting tragedy. American Communication Journal, 6(2). Retrieved from http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol6/iss2/articles/larson.htm Milliman, J., Taylor, S., & Czaplewski, A. J. (2002). Cross-cultural performance feedback in multinational enterprises: Opportunity for organizational learning. Human Resource Planning, 25(3), 29-43. Mortensen, D. C. (1997). Miscommunication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Olsina, E. C. (2002). Managing understanding in intercultural talk: An empirical approach to miscommunication. Atlantis, 24(2), 37-57. Palmeri, J. (2004). When discourses collide: A case study of interprofessional collaborative writing in a medically oriented law firm. Journal of Business Communication, 41(1), 37-65. Rosile, G. A. (2003). To head knowledge: Critical dramaturgy and artful ambiguity. Management Communication Quarterly, 17(2), 308-314. Shannon, C., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Stein, R. (2003, August 27). Miscommunication, bungling halted bid for shuttle photos. The Washington Post, p. A1. Sullivan, J., & Kameda, N. (1982). The concept of profit and Japanese-American business communication problems. Journal of Business Communication, 19(1), 33-39. Sullivan, J., Kameda, N., & Nobu, T. (1991). Bypassing in managerial communication. Business Horizons, 34(1), 71-80. Turner, P. K., & Krizek, R. (2006). A meaning-centered approach to customer satisfaction. Management Communication Quarterly, 20(2), 115-147.