LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION Where is

advertisement

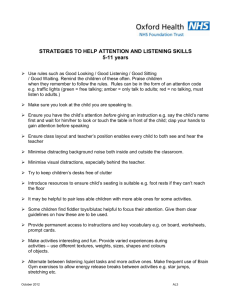

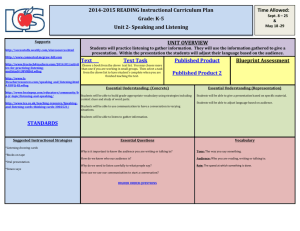

Running head: LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION Where is Listening Instruction Today: A Research Proposal to Survey Colleges and State Universities Robert L. Kehoe International Listening Association Certified Listening Professional Program Dr. Halley and Dr. Wolvin February 10, 2014 LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 2 Abstract The need for college level listening instruction has long since been emphasized and documented. However, there is a dearth of current information where one may go to find this kind of instruction in the colleges and universities in the United States, and there is a lack of information that speaks the location, quality of instruction, or instructor qualifications. In order to fill these gaps in information it is proposed that survey research be conducted to answer research questions concerned with location, context of the instruction, and instructor readiness. LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 3 Where is Listening Instruction Today: A Survey of Junior Colleges and State Universities The significance of learning how to listen effectively has expanded in the past eight decades. It has reached a lofty position in the minds of educators and business owners everywhere. Any argument in reference to whether or not there is a need for listening skills training is settled. Business leaders have agreed that effective listening skills are valuable in the workplace (Flynn, Valikoski, & Grau, 2008; Smeltzer, & Watson, 1985 ). Educators have signed on to the fact that a student’s performance and academic success is related to the learning of effective listening skills (Conaway, 1982; Brown, 1987; Wolvin & Coakley, 2001; Brownell, 2013). The agreement between these two groups stems from the recognition of “the centrality of listening in human communication” and from the broad documentation of the importance of effective listening in studies by listening scholars (Wolvin, Coakley, & Disburg, 1990). The consensus is high, but are we convincing college administrators to add this most needed communication curriculum? Where is listening instruction available in higher education, how is it taught, and how are the instructors qualified to teach listening? Searching the internet using the search terms “colleges that offer listening courses” yielded over 272 million items. Obviously, that would be a time consuming task. The problem is there is a gap in information when one wants to find which colleges offer a course in listening, the context of the listening course, and information on the instructors and their experience. Research in this area of communication could provide a resource for locating listening instruction in colleges and universities. Research Proposal Proposing research should begin with the researchers asking five fundamental questions: (1) What is the topic, (2) what is the problem, (3) why is it worth studying, (4) does the proposed LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 4 study have practical significance, (5) does it contribute to the construction of social theories (Babbie, 2006, p. 114)? The following paragraphs will address these five questions. The topic is listening instruction in higher education. Specifically answering the questions about where listening is offered as a course or unit, what is taught, and what are the qualifications of the instructor? Why is it worth studying? Perhaps there are many reasons for studying the quality and quantity of listening instruction in colleges and universities; however, the following three reasons seem to standout most prominently. First, there is a dearth of research in the quality and quantity of listening instruction in colleges and universities in the United States. There have been four such research projects since 1990. Second, since that time, no known study has duplicated any of these studies to ascertain the quantity or enhancement of the quality (exposing students to the affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions of learning to listen) of listening instruction in those colleges and universities. Third, if part of our goal, as listening and communication scholars, is to see listening instruction grow in higher education we do not have a current measurement. This study can assist us to understand our rate of success. Fourth, this study will examine a different group of colleges and universities than studied in previous research. Only colleges that are accredited by one of the six regional accrediting bodies will be surveyed. Does the proposed study have practical significance? Yes. The practical significance of this study is the development of a the list of colleges and universities that provide listening instruction. The final list will represent colleges and universities that actively give instruction in listening across the United States. Additionally the master list will associate listening instruction with location, quality, and instructor qualifications. LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 5 Does it contribute to the construction of social theories? No. This is a quantitative study that will answer questions associated with availability, the perimeters of listening instruction, and what are the qualifications of those teaching. Considering the research falls under the auspices of description I can only predict the research may contribute to descriptive theory. “Descriptive theories are concerned with providing a description of what people actually do” (Hogue, 2012). In summary, the answers to these questions provide evidence and give reason to proceed with research in listening instruction. There is a gap in the research. The study is practically significant because it could inform us on the quality and quantity of listening instruction in higher education. Finally, the study could contribute to descriptive theory of how listening is taught. Review of Literature Research to locate listening instruction courses in institutions of higher education is sparse. Research describing how listening instruction is performed in higher education courses has also suffered from a dearth of information. Search of the Internet using two different browsers yielded four such research articles. Two of the articles focused on where listening instruction is taking place in higher education. The other two articles focused on the content of the listening instruction in higher education classroom. Each article emphasized the need for listening instruction. Wolvin, Coakley, and Ginsberg (1990) suggest students need listening skills for academic survival and that listening is central to human communication thereby citing the value of listening instruction. Wacker and Hawkins (1995) make the point that much of a person's time communicating is listening and suggest, "Listening should definitely be part of the communication curriculum"(p.15). Again, Wolvin, Coakley, and Dinsburg (1992) “Listening plays a critical role in the lives of students” (p.59). LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 6 Finally, Perkins (1994) contends that ”students could benefit from instruction in listening” while citing the numbers of students who do not receive any instruction (p. 82). Finding where listening instruction is offered in American colleges and universities is explicit in the purpose of two research articles. “It is the purpose of this study, then, to update developments in listening course and units in American colleges and universities………….”( Wolvin, Coakley, and Dinsburg, 1990, p.3). “[It] would be useful to go beyond the ILA membership to ascertain if listening is being offered in other colleges and universities” (Wolvin, Coakley, and Dinsburg, 1992, p. 59). The how and what of listening instruction in higher education is answered in the research of Perkins (1994) and Walker and Hawkins (1995). While these researches were interested in the where of listening instruction, their focus was mainly on matters of curriculum. Perkins (1994) considered his work to be a benchmark for future research in listening instruction. Perkin’s study ask who takes the basic speech course, what types of listening are taught, how is listening taught, who teaches the basic speech course with what kind of training in listening does the instructor have. Walker and Hawkins (1994) focused on a comparison of different listening instruction programs. Their study asks instructors what areas of listening instruction they feel are high average, and low. Thirteen critical areas of teaching listening are analyzed for the emphasis given by the instructor. Wacker and Hawkins (1995) considered theses thirteen areas ac critical for listening instruction: “(a) listening as part of the of communication process; (b) the physiological process; (c) the psychological aspect the listening process; (d) being committed to listening; (e) setting a goal to listen; (f) paying attention to non verbal ques; (g) classroom listening and note taking; (h) critical listening; (i) aesthetic listening; (j) comprehensive listening; LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 7 (k) relational listening; (l) gender differences in listening; and (m) practicing listening skills” (p. 15). A look at how the articles disagreed and agreed will be used to discuss the findings of these research articles. There are fewer places where the research findings disagreed than not. Disagreement centered around three items of what is taught in a listening course, what level of college student participates most, and which colleges should be surveyed. Agreement centered on finding listening instruction as a unit in another course, the dimension most frequently used a a focal point for the instruction, and the degree of training the instructor of the listening course had. The disagreement of what is taught can be found in the research by Perkins (1994) and Wacker and Hawker (1995). Perkins (1994) found less time is spent teaching listening skills and more time was devoted to theory and basic information on listening. However, Wacker and Hawker (1995) contend in their study that practicing skills received a very high emphasis in the course work they analyzed. The college level of the students in a listening class is another point of disagreement. In the research by Wolvin, Coakley, and Dinsburg (1990) lower level college students were found as the most likely students to be enrolled. Wacker and Hackers (1995) findings differed. Their results indicated there are more upper levels students in the listening programs they analyzed. Lastly, the researchers disagreed on which colleges and universities should be surveyed. Three of the studies relied heavily on the institutions listed in the Speech Communication Association’s directory. Researchers Wacker and Hawkins (1995) compiled a list from the research by Dr. June H. Smith and Dr. Patricia Turner, 1993. The work by Smith and Turner (1993) revealed colleges that had listening courses and became the list for the work by Wacker and Hawkins. LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 8 On the agreement side of the research, we have the following. All of the articles were in agreement that the most likely place to find listening instruction is in Speech Communication courses. Listening instruction is most often taught as unit in another communication course. Teaching critical listening happened at a higher frequency and received a strong emphasis in the listening courses surveyed. Most instructors of the listening courses were lacking training in listening. Finally, researchers agreed that listening instruction needed to have more research. From the agreement and disagreement perspective of the articles reviewed, a decision can be made for a direction for the research in listening instruction. The agreement perspective tells me that most listening is taught as a unit in another course. If listening has become more important in a student’s education, will an increase in standalone courses, be found? Therefore, we might ask if this has changed by asking the following research question: R¹ Which regionally accredited colleges has a standalone listening course or a listening a unit within another course? The literature review revealed that critical listening was highly emphasized in course work and frequently was what was taught in a listening unit or course. Is the growth in listening importance changing this trend to give equal instruction time for the affective and behavioral dimensions of listening? What could be found is a more balanced approach to listening instruction that includes the concepts of empathy and attending behaviors of listening. In this way listening instruction would include the affective and behavioral dimensions of listening. Therefore a second research question could be: R² What percentage of time is spent in each of the three listening dimensions of affective, cognitive, and behavioral? LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 9 Researchers have found that most instructors that teach listening have not had formal training. It would seem that this statistic could have changed due to listening education’s ascension of importance when compared to speaking and writing. A third research question may ask: R³ To what degree has the instructor of the listening course had training in listening instruction? Subjects for the Study The subjects of this study are the Communication Departments of colleges and universities that are accredited by one of the six regional accreditation bodies. The six bodies are: (1) Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools, (2) New England Association of Schools and Colleges, (3) North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, (4) Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities, (5) Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, (6) Western Association of Schools and Colleges. Due to time constraints and scheduling the 209 colleges and universities in the Western Association of Schools and Colleges are the subject of this research. Future research will include the remaining regions in separate studies culminating in a list for all six regions. A purposive sample will be taken of the 209 colleges and universities in the Western Association of Schools and Colleges. It is the judgment of the researcher that only the colleges with a Communication Department from this sample will be include in the research. This is because past research indicated that most listening courses are offered in Speech and Communication courses. Typically, Speech and Communication is taught from a Communication Department. Measurement LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 10 The variables of this research are the presence of listening instruction, higher and lower quality of listening instruction, and the qualifications of the instructor. Definitions for these variables are as follows. Presence of listening instruction is defined by the existence of a course within a course or a standalone course. Listening courses within a course are required to be at least one chapter in the textbook or one unit of the course. Higher quality listening courses mean the course will have a balance of the study of listening as affective, behavioral, and cognitive. Lower quality listening courses will focus more on one dimension than the others will. In other words, courses that spend unequal time in each dimension of listening would be deemed to have less quality. Instructor qualifications are defined as the presence of a certificate in listening, seminar certification, or college level instruction in the field of listening. Data Collection Measurement of these variables will be taken from survey questions (see Appendix A). The survey questions have been formulated by the researcher and ideas from questions asked by Perkins (1994). Surveys will be sent by e-mail to Communication Department Chairs for completion. Analysis The analysis for this study is rooted in precise description. Data will be examined for physical location of listening instruction. Listening instruction quality and the listening instructors’ qualifications will be evaluated for each location in the analysis. The analysis will be used to form a chart showing the exact location of listening instruction, the quality of the instruction and the qualifications for the instructor. Students that are making a decision to attend a certain college or university will be able to ascertain listening instruction is available, its context, and see information about instructors. LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION Schedule The schedule for the research is provided below. 01/06/14 to 01/20/14 Locate contacts in the 209 colleges and universities in WASC Send survey to contacts via email 01/20/14 to 02/10/14 Analyze data from returned surveys Categorize institutions on spread sheet Develop chart 02/24/14 to 03/17 Write research paper. 11 LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 12 References Brown, J.I. (1987). Listening ubiquitous yet obscure. International Journal of Listening, 1,(1), 314. Retrieved from www.listen.org Flynn, J., Valikoski, T., & Grau, J. (2008). Listening in the business context: Reviewing the state of research. International Journal of Listening, 22(2), 141-151. doi: 10.1080/10904010802174800 Ford, W. S. Z., Wolvin, A. D., & Chung, S. (2000): Students' self-perceived listening competencies in the basic speech communication course. International Journal of Listening, 14(1), 1-13. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2000.10499032 Hogue, J.L. (20120. Theories – descriptive/prescriptive learning theories / instructional design theories. Retrieved from http://rjh.goingeast.ca/2012/03/04/theoriesdescriptiveprescriptive-learning-theories-instructional-design-theories/ Hopper, J. E. (2007): An exploratory essay on listening instruction in the K-12 curriculum, International Journal of Listening, 21(1), 50-56. doi: 10.1080/10904010709336846 Johnson, I. D., & Long, K.M. (2007). Student listening gains in the basic communication course: A comparison of self-report and performance-based measure. International Journal of Listening, 21(2), 92-101. doi: 10.1080/10904010701301990 Rankin, P.T. (1926). The measurement of the ability to understand spoken language. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Michigan, Detroit, MI Perkins, T. M. (1994). A survey of listening instruction in the basic speech course. International Journal of Listening, 8(1), 80-97. doi: 10.1080/10904018.1994.10499132 Smeltzer, L.R., & Watson, K. W. (1985). A test of instructional strategies for listening improvement in a simulated business setting. Journal of Business Communication, 22(4) 33-42. doi:1177/002194368502200405 LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 13 Wolvin, A. D., & Coakley,C.G. (2001). Listening education in the 21st century. International Journal of Listening, 14, 143-152. doi: 10.1080/10904018.2000.10499040 Wolvin, A. D., Coakley C. G., &. Disburg, J. E. (1992). Listening instruction in selected colleges and universities. International Listening Association Journal. 6:1, 59-65 doi:10.1080/10904018.1992.10499108 Wolvin, A. D., Coakley C. G., &. Disburg, J. E. (1990). The status of listening instruction in American colleges and universities. International Listening Association Journal. LISTENING INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION 14 Appendix A Listening Instruction Survey Questions R¹ Which regionally accredited colleges has a standalone listening course or listening as a unit within another course ? 1. What is the name of your institution? 2. Where is its location? City_________ State__________ 3. Is listening instruction offered as a standalone course? 4. Is listening instruction offered as a unit within another course? R² What percentage of time is spent in each of the three listening dimensions of affective, cognitive, and behavioral? 5. What percentage of time of the whole course or unit is spent teaching the affective dimension of listening? 6. What percentage of time of the whole course or unit is spent teaching the cognitive dimension of listening? 7. What percentage of time of the whole course or unit is spent teaching the behavioral dimension of listening? R³ To what degree has the instructor(s) of the listening course had training in listening instruction? 8. General overview? 9. Certification, special classes, seminars? 10. No training?