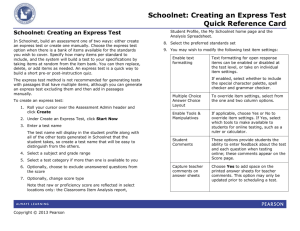

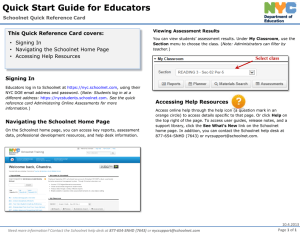

Schoolnet Vol.3_1_Cover1

advertisement