Evaluation of Swedish Support to SchoolNet Namibia

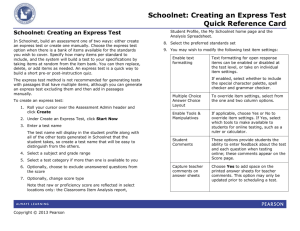

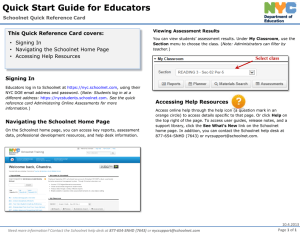

advertisement