GUIDELINES ON STATISTICS OF TANGIBLE ASStS

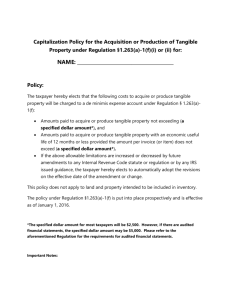

advertisement