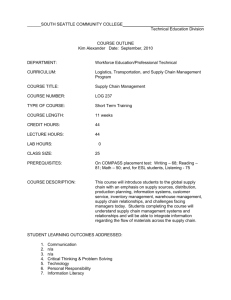

Transport Logistics - International Transport Forum

advertisement