Is There Anything Good About Rate My Professor?

advertisement

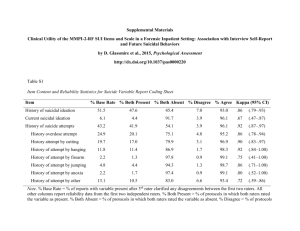

AN EXPLORATORY STUDY: IS THERE ANYTHING GOOD ABOUT RATEMYPROFESSOR? Richard L. Peterson Department of Management & Information Systems Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07043, 973-655-7038 petersonr@mail.montclair.edu Mark L. Berenson Department of Management & Information Systems Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07043, 973-655-6857 berensonm@mail.montclair.edu Risha Aijaz Department of Management & Information Systems Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07043, 973-655-4335 aijazr1@mail.montclair.edu ABSTRACT Professor rating services such as RateMyProfessor.com are frequently dismissed as invalid due to their inherent nature of self selection. Only raters at the extremes, so the theory goes, contribute to the site as they have axes to grind or high praises to deliver. The middle, supposedly more even handed raters don’t bother to offer ratings or comments. While rater bias on these sites seems logical in theory, is it actually true? RateMyProfessor provides an opportunity to test for bias in the comments offered by the raters. If these verbal evaluations are biased the language used would be extreme and outside the boundaries of normal written discourse. The work of Hart [8] and others provides both a software tool for textual analysis and normative data on nine ―dimensions of language‖. The exploratory research reported here examines written comments for individual professors. We evaluate the comments of positive and negative raters to the norms of discourse across a variety of genres and identify language dimensions where raters truly are extreme and where they are not. KEYWORDS: Professor Ratings, Text Analysis, Content Analysis Author Notes: Correspondence concerning this manuscript should be sent to: Mark Berenson, Department of Management and Information Systems, School of Business, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07043; Phone: (973) 655-6857; E-mail: berensonm@mail.montclair.edu. INTRODUCTION Ten years after being created, RateMyProfessor.com (RMP) today is the most popular and widely used website by students to provide ratings and comments about their professors; with more than 10 million opinions of over 1 million professors. The ratings cover more than 6,000 schools across the United States, Canada, England, Scotland, and Wales*. It’s appreciated by students ―shopping‖ for professors, but dismissed by empiricists for its self-selection of raters violates the bedrock principle of random selection RMP offers two sources of data: numeric ratings and textual comments. Raters are presented with a 1-5 scale: Easiness Hard Easy Helpfulness: Extremely Helpful Useless Clarity: Incomprehensible Crystal Interest level prior to attending class: None at all It's my world! Appearance: (just for fun) Hot Not An Overall Quality rating is calculated from Helpfulness and Clarity. Other information solicited—but not displayed--includes: Textbook Use (5-point scale from ―Low‖ to ―High,‖ Textbook Used (by name or ISBN), Grade, Attendance (Mandatory or Not Mandatory), Professor Status (Still Teaching, Retired/Gone), and Class and Section (both fill-in). Finally, RMP includes a 350 character text box for students to type comments. The text box includes a prominent note ―Please keep comments clean. Libelous comments will be deleted.‖ Also included are warnings ―Remember, YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE for what you write here. Submitted data become the property of RateMyProfessors.com. IP addresses are logged.‖ Adjacent to the Comments field is a label ―Guidelines‖ that links to page of ―Dos‖ and ―Don’ts‖ for raters which is reproduced as Appendix A. Despite the best intentions of those responsible for the development of RateMyProfessors.com, one must seriously question the value of the numerical ratings provided because the raters ―self-select,‖ violating the tenet of random selection needed for drawing overall inferences from any survey or designed experiment. It has long been surmised that the majority of those students who decide to participate in the evaluation process hold distinctly bipolar views of the faculty member they are rating. Students with a legitimate or perceived gripe are more likely to participate in the ratings, as are students who very much appreciate or value what the faculty member has contributed to the course. A third group of raters, asserted to be far fewer in number, believe the faculty member being rated is ―okay/average‖ but feel obligated to participate in the rating process because of their responsibility to fraternity, sorority or fellow classmates. Thus it is conjectured that the distribution of RMP evaluations will be U-shaped for most faculty members, the majority of ratings being ―Good‖ or ―Poor,‖ with a minority of ratings being ―average.‖ On the other hand, had universal/mandatory ratings been required, as may be the case at various institutions of higher learning, whether a 3-point rating scale is used, or more popular 5 or 7-point Likert-type rating scales are used, one would hypothesize the distribution of ratings for most faculty would be unimodal with one of the tails (highest rating or lowest rating) being very limited in frequency count. Interestingly, and despite the problems of self-selection bias in the RMP ratings, Jaschik [12] has shown that there is a significantly positive correlation between the numerical RMP quality rating and the average rating computed from the student evaluations of the faculty by a whole class. As outlined in the Methodology, using the RMP quality rating data for the faculty in the Management and Information Systems Department in the School of Business at Montclair State University along with the corresponding student evaluation ratings on campus, one aspect of this overall study will be to attempt to corroborate the findings reported in the study by Jaschik [12]. If we can’t trust the ratings per se due to bias, is it also the case that we can’t trust the comments? Are the comments also biased such that the language of the comments is somehow different from ―normal‖ language? Are raters somehow different from the ―general‖ population in terms of language usage? To make this determination we might compare the language of the comments of the raters on RMP to a variety of language samples. Content analysis of text is a research methodology that uses a set of procedures to analyze and categorize communication [20]. The methodology offers a number of potential benefits including the identification of individual differences among communicators [20], avoidance of recall biases [1], and the ability to obtain otherwise unavailable information [13]. In the business disciplines content analysis has been used in accounting [17], management [2], marketing [19], and corporate strategy [15] [21]. There are three types of approaches to language analysis 16]: human-scored procedures, artificial intelligence systems, and individual word count systems. With the first approach, coding rules are established, human coders are trained, and then the coders classify selected aspects of the text. Artificial intelligence approaches consider the lexicon, syntax, and semantics of text [18]. With respect to individual word count methodology, individual words in the text are counted and the frequency of each word is compared to the frequency of these same words in other communication samples. Word frequencies outside of the range of frequencies in these comparative samples are an indication of differences between the samples. DICTION [8] is one of a number of word frequency programs. In DICTION the frequency of word usage in the analyzed text is compared to the frequency of word usage across various genres studied by Hart [7] [4] [5] [9] [10]. The genre(s) to which the analyzed text is compared may be selected from business, daily life, entertainment, journalism, literature, politics, and scholarship. Hart [11] analyzed from one to six sub-genres to derive word frequency norms for each genre. In total, the norms are based on the analysis of 22,027 texts of various genres written between 1948 and 1998. The words from these genres are arranged in 33 dictionaries or word lists ranging in size from 10 to 745 words. No word appears in more than one dictionary. Brief descriptions of each dictionary may be found in Appendix B. In addition to the absolute frequency counts, DICTION calculates four variables based on word ratios. These calculated variables are: Insistence, a measure of ―code-restriction‖ that indicates a ―preference for a limited, ordered world‖; Embellishment, a measure of the ratio of adjectives to verbs; Variety, a measure of conformity to, or avoidance of, a limited set of expressions (different words/total words); and Complexity, a measure of word size based on the Flesch[3] method. Frequency counts from the various dictionaries along with the four calculated compose five master variables. Hart’s [11] master variables, intended to capture the tonal features of the text, are defined and formulated as follows: Certainty is a measure of language ―indicating resoluteness, inflexibility, and completeness and a tendency to speak ex cathedra.‖ Certainty = [Tenacity. + Leveling. + Collectives. + Insistence] [Numerical Terms + Ambivalence. + Self Reference + Variety] Activity is a measure of ―movement, change, [and] the implementation of ideas and the avoidance of inertia; Activity = [Aggression. + Accomplishment. + Communication. + Motion] - [Cognitive Terms. + Passivity. + Embellishment] Optimism is a measure of ―language endorsing some person, group, concept or event or highlighting their positive entailments.‖ Optimism = [Praise + Satisfaction + Inspiration] - [Blame + Hardship +Denial] Realism is a measure of language ―describing tangible, immediate, recognizable matters that affect people’s everyday lives.‖ Realism = [Familiarity + Spatial Awareness. + Temporal Awareness. +Present Concerns. + Human Interest + Concreteness] - [Past Concern + Complexity] Commonality is a measure of language ―highlighting the agreed-upon values of a group and rejecting idiosyncratic modes of engagement." Commonality = [Centrality. + Cooperation. + Rapport] - [Diversity + Exclusion + Liberation] SPECIFIC RESEARCH QUESTIONS In RMP an Overall Quality rating is calculated from the raters’ numerical evaluations of ratings of professors’ Helpfulness and Clarity. For each professor rated, RMP categorizes the professor’s Overall Quality as ―Good,‖ ―Average,‖ or ―Poor.‖ In this exploratory study of the textual comments of raters we questioned whether there would be significant differences among the comments created by raters classified in each category of Overall Quality compared to the general population as defined by the dictionaries included in DICTION. Specifically, the questions addressed were: Are there significant differences in the commentary provided by RMP evaluators who rate professors ―Good‖ versus those who rate professors ―Poor‖ with respect to the master variables? Are there significant differences in the commentary provided by RMP evaluators who rate professors ―Good‖ versus those who rate professors ―Poor‖ with respect to the five content-analysis master variables? Are there significant differences in the commentary provided by RMP evaluators who rate professors ―Good‖ versus those who rate professors ―Poor‖ with respect to the four content-analysis calculated variables? For the Master variables of DICTION, we hypothesized as follows: Certainty. As a measure of resoluteness, the group of raters rating professors as ―Poor‖ will be more certain in their language than those rating the professor as ―Good.‖ This certainty will be revealed in higher scores for tenacity, leveling, collectives, insistence, numerical terms, ambivalence and self-references. ―Poor‖ raters will also show this certainty by a reduced variety of words. Activity. This measure of movement will show ―Poor‖ raters with greater activity. Words of aggression, accomplishment, and communication will be higher for this group. They will also use more terms of passivity, and more embellishments. ―Good‖ and ―Poor‖ raters will use more cognitive terms than the ―Average‖ Optimism. ―Good‖ and ―Poor‖ raters will reflect their ratings in their choice of words in their comments. ―Good‖ raters will use more terms of praise, satisfaction, and inspiration. ―Poor‖ raters will do the opposite; fewer terms of praise, satisfaction, and inspiration. In addition, while :Good‖ raters will not avoid blame, hardship, and denial, ―Poor‖ raters will use more of these terms than would be usual. Realism. There will be no significant differences in the frequency of word use in any dictionary making up this master variable either for ―Good‖ or ―Poor‖ raters. Commonality. ―‖Good‖ raters will use above average numbers of words of centrality, cooperation and rapport while ―Poor‖ raters will use fewer of these words. These raters will indicate their feelings of exclusion and liberation by more frequent use of these terms. METHODOLOGY For this exploratory study we restricted the data set to all full-time, tenure/tenure-track faculty teaching in a department within a school of business at a public university who had entries on RateMyProfessor. Of the 23 faculty members in the department over the period, 100 percent had ratings on RMP. As we were interested in studying raters who were or planned to be business students, given that some professors also had expertise in other disciplines and taught some courses outside the school of business, we eliminated all ratings and comments for any professor where the reported experience with the professor was in a course not offered by the department. This resulted in the elimination of 18 RMP records of the 700 total. Ratings without comments (a total of 17) were also eliminated as these comments were the focus of current study. Finally as our interest was on ratings and comments at the extremes we eliminated 106 raters whose Overall Quality rating was ―Average.‖ The comments of the remaining 559 raters were then cleaned to correct misspellings and abbreviations that would impact the word frequency counts. No other changes were made to the corpus. Text files of all the comments from ―Good‖ and ―Poor‖ raters and a combined file were created and submitted to DICTION. All words were processed (DICTION allows sampling of the corpus) and no custom dictionaries were created for the analysis. AN EXPLORATORY ANALYSES OF SPECIFIC RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS Table 1 displays the DICTION reported results for the two groups of ratings, ―Good‖ versus ―Poor,‖ for each of the five master variables and their corresponding component variables. Also indicated is whether or not our hypothesized directions of results were confirmed. The results indicate that for the five master variables of DICTION our combined hypotheses were not consistently confirmed, nor were they for the component variables. Table 1 – Dictionary, Constructed, and Master Variable Results for ―Good‖ and ―Poor‖ Raters Variable Frequency Good Frequency2 Poor Hypothesis: Poor vs. Good 6.09 7.25 Ambivalence 18.09 17.30 Self-reference 7.80 8.58 Tenacity 36.01 46.70* Leveling Terms 11.52 15.21* Collectives 12.57 8.85 17.01* 5.99 Satisfaction 2.82 3.67 Inspiration 1.22* 1.31* Blame 6.20* 15.53* Hardship 1.16* 3.32 1.28 0.05* Accomplishment 3.65* 3.87* Communication 10.20 11.97* Cognition 10.27 19.70* Passivity 2.23 2.82 2.09* 4.37 80.85* 89.63* Temporal Terms 4.56* 8.56 Present Concern 13.09 19.66* Human Interest 41.20 58.05* Concreteness 10.24* 16.01 Past Concern 3.03 2.44 Centrality 0.26* 1.11* Rapport 0.17* 1.56 15.09* 11.09* > > > > > > < < < > > > > > ? > ? ? ? ? ? ? ? < < < 0.39 0.52 ? Numerical Terms Praise Aggression Spatial Terms Familiarity Cooperation Diversity Exclusion 0.29 0.31 Liberation 0.53 0.30 Denial 9.43* 20.95* Motion 2.44 1.61 Calculated Variables Good Poor Insistence 73.04 2.51 Embellishment 1.55* 1.00 0.47 0.46 3.93* 4.25* Variety Complexity Master Variables Good Poor Activity 47.60 6.32 Optimism 50.20 9.31 Certainty 51.97 2.87 Realism 46.00 9.92 Commonality 52.53 2.53 > > > ? Hypothesis: Poor vs. Good > > < ? Hypothesis: Poor vs.Good > < > ? < The first surprising result occurred with the master variable certainty where the ―Good‖ raters scored higher than the ―Poor‖ raters. However, for the eight component variables we correctly hypothesized the result five times and were wrong three times. The second surprising result occurred with the master variable activity. The ―Good‖ raters again scored higher than the ―Poor‖ raters. However, for the seven component variables we correctly hypothesized the result three times and were wrong twice. We did not hypothesize and difference in results for two component variables. For the master variable optimism our hypothesis was confirmed. The ―Good‖ raters again scored higher than the ―Poor‖ raters. On the other hand, for the six component variables we correctly hypothesized the result four times and were wrong twice. For the master variable realism we did not hypothesize any difference in direction of results for ―Good‖ versus ―Poor‖ raters, nor did we make any hypotheses for the eight component variables. For the master variable commonality our hypothesis was confirmed. The ―Good‖ raters again scored higher than the ―Poor‖ raters. On the other hand, for the six component variables we correctly hypothesized the result only two times and were wrong three times. We did not hypothesize the direction of the results for one of the component variables. DISCUSSION From Table 1 it is observed that the ―Good‖ raters outscored the ―Poor‖ raters on four of five master variables and our hypothesized results were only confirmed twice. For one master variable, realism, we did not specify a preconceived difference in direction and that was the only master variable that demonstrated higher scores for the ―Poor‖ raters. Breaking these results down by the components of the five master variables, we correctly hypothesized results 14 times, we were incorrect 10 times and on 11 occasions we did not attempt to predict the direction of the results. The question that must be pondered is why such unexpected results? A few possibilities must be thoroughly examined. 1 – As asked rhetorically in the Introduction section, if we can’t trust the numerical ratings per se due to bias, is it also the case that we can’t trust the comments? Are the comments also biased such that the language of the comments is somehow different from ―normal‖ language? Are raters somehow different from the ―general‖ population in terms of language usage? To make this determination we may need to compare the language of the comments of the raters on RMP to a variety of language samples, not just the DICTION program.. 2 – Although much has been written about the DICTION program in various articles by Hart [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] and others who have used it for research one must question its validity reliability which have not been reported. Furthermore, there is no readily found description of the computation of mean and standard deviation, or computation of the standard Z scores and Hart fails to demonstrate why he breaks with long-held convention and describes absolute Z scores greater than 1.0 as outside the normal range and thereby significant. 3 – Hart’s [10] five master variables appear to be independent constructs arising from a factor analysis – there is little to no correlation among these constructs. The component variables comprising the five master variables did not seem to consistently display the direction of difference expected by our hypotheses, perhaps a misunderstanding on our part of the definition of the involved terms? 4 – It is impossible for us to determine how the DICTION program searches for discrepancies in various commentary that could result in misclassification. For example, it is not known whether the DICTION program can properly classify a comment about teacher performance that says ―the teacher is easy‖ versus ― the teacher is not easy‖ versus ―I was told the teacher was easy but I don’t think this is so.‖ If the DICTION program cannot properly distinguish among such responses both its reliability and validity as a measuring instrument can be questioned. Further exploration will provide answers to the above. CONCLUSIONS Despite the surprising findings which indicated discrepancies with several of our hypotheses we remain encouraged by the results of this exploratory study. Once we satisfactorily address the aforementioned dilemmas described in the Discussion section we plan to extend the study and address additional questions in two phases: :Phase I Questions Is there a significantly positive correlation between the biased RMP quality ratings of the faculty in the Management and Information Systems Department in the School of Business at Montclair State University and the corresponding campus student evaluations received by these faculty? That is, do the MGIS Department data corroborate the findings reported in the study conducted by Jaschik [12]? Omitting ―Average‖ ratings, are the percentage of ―Good‖ to ―Good‖ or ―Poor‖ ratings significantly higher from the class evaluations than from the RMP evaluations? An affirmation of this hypothesis is proof of the negative self-selection bias in the RMP ratings. Phase II Questions Given the self-selection bias issues, using the Management and Information Systems Department faculty ratings in the School of Business at Montclair State University as a base, is there a statistically significant difference between the RMP quality ratings of these faculty and those given to a randomly selected sample of similar faculty from corresponding/similar AACSB-International public universities? Are there significant differences in the commentary provided by RMP evaluators who rate professors ―Good‖ versus those who rate professors ―Poor‖ with respect to the 33 content-analysis dictionary variables between the aforementioned Montclair State University faculty and the randomly selected faculty? Are there significant differences in the commentary provided by RMP evaluators who rate professors ―Good‖ versus those who rate professors ―Poor‖ with respect to the five content-analysis master variables between the aforementioned Montclair State University faculty and the randomly selected faculty? Are there significant differences in the commentary provided by RMP evaluators who rate professors ―Good‖ versus those who rate professors ―Poor‖ with respect to the four content-analysis calculated variables between the aforementioned Montclair State University faculty and the randomly selected faculty? REFERENCES [1] Barr, P. S., Stimpert, J. L., & Huff, A. S. (1992). Cognitive Change, Strategic Action, and Organizational Renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 15-36. [2] Fiol, C. M. (1989). A semiotic analysis of corporate language: Organizational boundaries and joint venturing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 277-303. [3] Flesch, R. (1951). The Art of Clear Thinking. New York: Harper. [4] Hart, R. P. (1984a). Systematic analysis of political discourse: The development of DICTION. K. Sanders, L. Kaid, & D. Nimmo (Eds.), Political Communication Yearbook (pp. 97-134). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [5] Hart, R. P. (1984b). Verbal Style and the Presidency: A Computerbased Analysis. New York: Academic. [6] Hart, R. P. (1987). The Sound of Leadership: Presidential Communication in the Modern Age. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [7] Hart, R. P., and S. Jarvis. (1997). Political Debate: Forms, Styles, and Media. American Behavioral Scientist 40: 1095-1122. [8] Hart, R. P. (2000a). DICTION 5.0: The Text-analysis Program. Thousand Oaks, CA: Scolari/Sage Publications. [9] Hart, R. P. (2000b). Campaign Talk: Why Elections are Good for Us. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [10] Hart, R. P. (2001). Redeveloping DICTION: Theoretical Considerations. In M. West (Ed.), Theory, Method, and Practice of Computer Content Analysis (pp. 26-55). New York: Ablex. [11] Hart, R. P. (2003). DICTION http://rhetorica.net.htm [12] Jaschik, S. (2007). Could RateMyProfessors.com be Right? Inside Higher Education. June:1–2. [13] Kabanoff, B., Waldersee, R., & Cohen, M. (1995). Espoused values and organizational change themes. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1075-1104. [14] McCain, J. (2010) 4 Great Sites to Rate and Review Teachers & Professors http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/4-great-sites-rate-reviewteachers-professors/ [15] Merchant, H. (2004). Revisiting Shareholder Value Creation via International Joint Ventures: Examining Interactions among Firm- and Context-specific Variables. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 21, 129-145. [16] Morris, R. (1994). Computerized Content Analysis in Management Research: A Demonstration of Advantages & Limitations. Journal of Management, 20, 903-931. [17] Rogers, R. K., Dillard, J., & Yuthas, K. (2005). The Accounting Profession: Substantive Change and/or Image Management. Journal of Business Ethics, 58, 159-176. [18] Rosenberg, S. D., Schnurr, P. P., & Oxman, T. E. (1990). Content Analysis: A Comparison of Manual and Computerized Systems. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, 298-310. [19] Simon, M., & Houghton, S. M. (2003). The Relationship Between Overconfidence and the Introduction of Risky Products: Evidence from a Field Study. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 139-149. [20] Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic Content Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [21] Yuthas, K., Rogers, R., & Dillard, J. F. (2002). Communicative Action and Corporate Annual Reports. Journal of Business Ethics, 41, 141-157. APPENDIX A RateMyProfessor.com Posting Guidelines As a user of RateMyprofessors.com, you agree and accept the terms and conditions of the site. This site is a resource for students to provide and receive feedback on professor's teaching methods and insight into the courses. Comments should only be posted by students who have taken a class from the professor. Please limit one comment per person per course. The following guidelines are intended to protect all users-students and professors. Please review before posting on RateMyProfessors.com DOs: o o o Be honest. Be objective in your assessment of the professor. Limit your comments to the professor's professional abilities. Do not to get personal. o Proof your comments before submitting. Poor spelling WILL NOT cause your rating to be removed; however, poor spelling may result in your rating being discredited by those who read it. o Leave off your Name, Initials, Pseudo Name, or any sort of identifying mark when posting. o Refer to the Rating Categories to help you better elaborate your comments. o Remember that negative comments that still offer constructive criticism are useful. Comments that bash a professor on a personal level are not. o Submit helpful comments that mention professor's ability to teach and/or communicate effectively, course load, type of course work and course topics. DO NOTs: o State something as a fact if it is your opinion. o Post a rating if you are not a student or have not taken a class from the professor. o Post ratings for people who do not teach classes at your college or university. o Input false course or section codes for a class that does not exist. o Rate a professor more than once for the same class. o Make references to other comments posted. o Professors : Do not rate yourselves or your colleagues. Comments will be deemed inappropriate that are libelous, defamatory, indecent, vulgar or obscene, pornographic, sexually explicit or sexually suggestive, racially, culturally, or ethnically offensive, harmful, harassing, intimidating, threatening, hateful, objectionable, discriminatory, or abusive, or which may or may appear to impersonate anyone else. COMMENTS THAT CONTAIN THE FOLLOWING WILL BE REMOVED : Profanity, name-calling, vulgarity or sexually explicit in nature Derogatory remarks about the professor's religion, ethnicity or race, physical appearance, mental and physical disabilities. References to professor's sex life (Including sexual innuendo, sexual orientation or claims that the professor sleeps with students). Claims that the professor shows bias for or against a student or specific groups of students. Claims that the professor has been or will be fired, suspended from their job, on probation. Claims that the professor engages or has previously engaged in illegal activities (drug use, been incarcerated.) Includes a link/URL to a webpage or website that does not directly pertain to the class. Any piece of information including contact info that enables someone to identify a student. Any piece of information about the professor that is not available on the school's website and allows someone to contact them outside of school. This also includes remarks about the professor's family and personal life. Accusations that the professors is rating themselves or their colleagues. Is written in a language other than English? Unless you attend a French-Canadian school. The Do Nots of these Posting Guidelines will be enforced and violations will result in either the rating's comment being removed, or the entire rating being deleted. If you see a rating that you believe violates Posting Guidelines, please click the red flag and state the problem. It will be evaluated by RateMyProfessors moderators. Please do not flag a rating just because you disagree with it. Comments containing a threat of violence against a person or any other remark that would tend to be seen as intimidating or intends to harm someone will deleted. RateMyProfessors will notify the authorities of your IP address and the time you rated. This is enough information to identify you. IP addresses will also be turned over to the proper authorities when presented with a subpoenas or court orders from a government agency or court. Multiple Ratings Multiple ratings / comments from the same IP in a short amount of time are automatically deleted on our backend to fight rating abuse. There is no differentiation between positive and negative comments. Please give only one comment per person per course. New Professors Requests to add a new professor can be submitted on the school page and will be added once approved by a moderator. Please only submit professors who currently teach a course at your college or university. http://www.ratemyprofessors.com/rater_guidelines.jsp APPENDIX B Descriptions of the Dictionaries and Scores Accomplishment: Words expressing task-completion (establish, finish, influence, proceed) and organized human behavior (motivated, influence, leader, manage). Includes capitalistic terms (buy, produce, employees, sell), modes of expansion (grow, increase, generate, construction) and general functionality (handling, strengthen, succeed, outputs). Also included is programmatic language: agenda, enacted, working, leadership. Aggression: A dictionary embracing human competition and forceful action. Its terms connote physical energy (blast, crash, explode, collide), social domination (conquest, attacking, dictatorships, violation), and goaldirectedness (crusade, commanded, challenging, overcome). In addition, words associated with personal triumph (mastered, rambunctious, pushy), excess human energy (prod, poke, pound, shove), disassembly (dismantle, demolish, overturn, veto) and resistance (prevent, reduce, defend, curbed) are included. Ambivalence: Words expressing hesitation or uncertainty, implying a speaker's inability or unwillingness to commit to the verbalization being made. Included are hedges (allegedly, perhaps, might), statements of inexactness (almost, approximate, vague, somewhere) and confusion (baffled, puzzling, hesitate). Also included are words of restrained possibility (could, would, he'd) and mystery (dilemma, guess, suppose, seems). Blame: Terms designating social inappropriateness (mean, naive, sloppy, stupid) as well as downright evil (fascist, blood-thirsty, repugnant, malicious) compose this dictionary. In addition, adjectives describing unfortunate circumstances (bankrupt, rash, morbid, embarrassing) or unplanned vicissitudes (weary, nervous, painful, detrimental) are included. The dictionary also contains outright denigrations: cruel, illegitimate, offensive, miserly. Centrality: Terms denoting institutional regularities and/or substantive agreement on core values. Included are indigenous terms (native, basic, innate) and designations of legitimacy (orthodox, decorum, constitutional, ratified), systematicity (paradigm, bureaucratic, ritualistic), and typicality (standardized, matter-of-fact, regularity). Also included are terms of congruence (conformity, mandate, unanimous), predictability (expected, continuity, reliable), and universality (womankind, perennial, landmarks). Cognitive Terms: Words referring to cerebral processes, both functional and imaginative. Included are modes of discovery (learn, deliberate, consider, compare) and domains of study (biology, psychology, logic, economics). The dictionary includes mental challenges (question, forget, re-examine, paradoxes), institutional learning practices (graduation, teaching, classrooms), as well as three forms of intellection: intuitional (invent, perceive, speculate, interpret), rationalistic (estimate, examine, reasonable, strategies), and calculative (diagnose, analyze, software, fact-finding). Collectives: Singular nouns connoting plurality that function to decrease specificity. These words reflect a dependence on categorical modes of thought. Included are social groupings (crowd, choir, team, humanity), task groups (army, congress, legislature, staff) and geographical entities (county, world, kingdom, republic). Communication: Terms referring to social interaction, both face-to-face (listen, interview, read, speak) and mediated (film, videotape, telephone, email). The dictionary includes both modes of intercourse (translate, quote, scripts, broadcast) and moods of intercourse (chat, declare, flatter, demand). Other terms refer to social actors (reporter, spokesperson, advocates, preacher) and a variety of social purposes (hint, rebuke, respond, persuade). Complexity: A simple measure of the average number of characters-per-word in a given input file. Borrows Rudolph Flesch's (1951) notion that convoluted phrasings make a text's ideas abstract and its implications unclear. Concreteness: A large dictionary possessing no thematic unity other than tangibility and materiality. Included are sociological units (peasants, AfricanAmericans, Catholics), occupational groups (carpenter, manufacturer, policewoman), and political alignments (Communists, congressman, Europeans). Also incorporated are physical structures (courthouse, temple, store), forms of diversion (television, football, CD-ROM), terms of accountancy (mortgage, wages, finances), and modes of transportation (airplane, ship, bicycle). In addition, the dictionary includes body parts (stomach, eyes, lips), articles of clothing (slacks, pants, shirt), household animals (cat, insects, horse) and foodstuffs (wine, grain, sugar), and general elements of nature (oil, silk, sand). Cooperation: Terms designating behavioral interactions among people that often result in a group product. Included are designations of formal work relations (unions, schoolmates, caucus) and informal associations (chum, partner, cronies) to more intimate interactions (sisterhood, friendship, comrade). Also included are neutral interactions (consolidate, mediate, alignment), job-related tasks (network, détente, exchange), personal involvement (teamwork, sharing, contribute), and self-denial (public-spirited, care-taking, self-sacrifice). Denial: A dictionary consisting of standard negative contractions (aren't, shouldn't, don't), negative functions words (nor, not, nay), and terms designating null sets (nothing, nobody, none). Diversity: Words describing individuals or groups of individuals differing from the norm. Such distinctiveness may be comparatively neutral (inconsistent, contrasting, non-conformist) but it can also be positive (exceptional, unique, individualistic) and negative (illegitimate, rabble-rouser, extremist). Functionally, heterogeneity may be an asset (far-flung, dispersed, diffuse) or a liability (factionalism, deviancy, quirky) as can its characterizations: rare vs. queer, variety vs. jumble, distinctive vs. disobedient. Exclusion: A dictionary describing the sources and effects of social isolation. Such seclusion can be phrased passively (displaced, sequestered) as well as positively (self-contained, self-sufficient) and negatively (outlaws, repudiated). Moreover, it can result from voluntary forces (secede, privacy) and involuntary forces (ostracize, forsake, discriminate) and from both personality factors (small-mindedness, loneliness) and political factors (rightwingers, nihilism). Exclusion is often a dialectical concept: hermit vs. derelict, refugee vs. pariah, discard vs. spurn). Familiarity: Consists of a selected number of C.K. Ogden's (1968) "operation" words which he calculates to be the most common words in the English language. Included are common prepositions (across, over, through), demonstrative pronouns (this, that) and interrogative pronouns (who, what), and a variety of particles, conjunctions and connectives (a, for, so). Hardship: This dictionary contains natural disasters (earthquake, starvation, tornado, pollution), hostile actions (killers, bankruptcy, enemies, vices) and censurable human behavior (infidelity, despots, betrayal). It also includes unsavory political outcomes (injustice, slavery, exploitation, rebellion) as well as normal human fears (grief, unemployment, died, apprehension) and incapacities (error, cop-outs, weakness). Human Interest: An adaptation of Rudolf Flesch's notion that concentrating on people and their activities gives discourse a life-like quality. Included are standard personal pronouns (he, his, ourselves, them), family members and relations (cousin, wife, grandchild, uncle), and generic terms (friend, baby, human, persons). Inspiration: Abstract virtues deserving of universal respect. Most of the terms in this dictionary are nouns isolating desirable moral qualities (faith, honesty, self-sacrifice, virtue) as well as attractive personal qualities (courage, dedication, wisdom, mercy). Social and political ideals are also included: patriotism, success, education, justice. Leveling: Words used to ignore individual differences and to build a sense of completeness and assurance. Included are totalizing terms (everybody, anyone, each, fully), adverbs of permanence (always, completely, inevitably, consistently), and resolute adjectives (unconditional, consummate, absolute, open-and-shut). Liberation: Terms describing the maximizing of individual choice (autonomous, open-minded, options) and the rejection of social conventions (unencumbered, radical, released). Liberation is motivated by both personality factors (eccentric, impetuous, flighty) and political forces (suffrage, liberty, freedom, emancipation) and may produce dramatic outcomes (exodus, riotous, deliverance) or subdued effects (loosen, disentangle, outpouring). Liberatory terms also admit to rival characterizations: exemption vs. loophole, elope vs. abscond, uninhibited vs. outlandish. Motion: Terms connoting human movement (bustle, job, lurch, leap), physical processes (circulate, momentum, revolve, twist), journeys (barnstorm, jaunt, wandering, travels), speed (lickety-split, nimble, zip, whistle-stop), and modes of transit (ride, fly, glide, swim). Numerical Terms: Any sum, date, or product specifying the facts in a given case. This dictionary treats each isolated integer as a single "word" and each separate group of integers as a single word. In addition, the dictionary contains common numbers in lexical format (one, tenfold, hundred, zero) as well as terms indicating numerical operations (subtract, divide, multiply, percentage) and quantitative topics (digitize, tally, mathematics). The presumption is that Numerical Terms hyper-specify a claim, thus detracting from its universality. Passivity: Words ranging from neutrality to inactivity. Includes terms of compliance (allow, tame, appeasement), docility (submit, contented, sluggish), and cessation (arrested, capitulate, refrain, yielding). Also contains tokens of inertness (backward, immobile, silence, inhibit) and disinterest (unconcerned, nonchalant, stoic), as well as tranquillity (quietly, sleepy, vacation). Present Concern: A selective list of present-tense verbs extrapolated from C.K. Ogden's list of "general" and "picturable" terms, all of which occur with great frequency in standard American English. The dictionary is not topicspecific but points instead to general physical activity (cough, taste, sing, take), social operations (canvass, touch, govern, meet), and task-performance (make, cook, print, paint). Past Concern: The past-tense forms of the verbs contained in the Present Concern dictionary. Praise: Affirmations of some person, group, or abstract entity. Included are terms isolating important social qualities (dear, delightful, witty), physical qualities (mighty, handsome, beautiful), intellectual qualities (shrewd, bright, vigilant, reasonable), entrepreneurial qualities (successful, conscientious, renowned), and moral qualities (faithful, good, noble). All terms in this dictionary are adjectives. Rapport: This dictionary describes attitudinal similarities among groups of people. Included are terms of affinity (congenial, camaraderie, companion), assent (approve, vouched, warrants), deference (tolerant, willing, permission), and identity (equivalent, resemble, consensus). Satisfaction: Terms associated with positive affective states (cheerful, passionate, happiness), with moments of undiminished joy (thanks, smile, welcome) and pleasurable diversion (excited, fun, lucky), or with moments of triumph (celebrating, pride, auspicious). Also included are words of nurturance: healing, encourage, secure, relieved. Self-Reference: All first-person references, including I, I'd, I'll, I'm, I've, me, mine, my, myself. Self-references are treated as acts of "indexing" whereby the locus of action appears to reside in the speaker and not in the world at large (thereby implicitly acknowledging the speaker's limited vision). Spatial Awareness: Terms referring to geographical entities, physical distances, and modes of measurement. Included are general geographical terms (abroad, elbow-room, locale, outdoors) as well as specific ones (Ceylon, Kuwait, Poland). Also included are politically defined locations (county, fatherland, municipality, ward), points on the compass (east, southwest) and the globe (latitude, coastal, border, snowbelt), as well as terms of scale (kilometer, map, spacious), quality (vacant, out-of-the-way, disoriented) and change (pilgrimage, migrated, frontier.) Temporal Awareness: Terms that fix a person, idea, or event within a specific time-interval, thereby signaling a concern for concrete and practical matters. The dictionary designates literal time (century, instant, mid-morning) as well as metaphorical designations (lingering, seniority, nowadays). Also included are calendrical terms (autumn, year-round, weekend), elliptical terms (spontaneously, postpone, transitional), and judgmental terms (premature, obsolete, punctual). Tenacity: All uses of the verb "to be" (is, am, will, shall), three definitive verb forms (has, must, do) and their variants, as well as all associated contractions (he'll, they've, ain't). These verbs connote confidence and totality. Source: Hart [11]