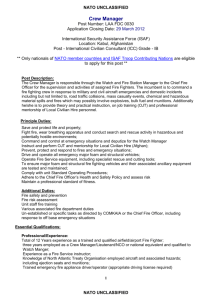

the three swords - Joint Warfare Centre

advertisement