EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IMPORTANT EMPLOYMENT CASES OF

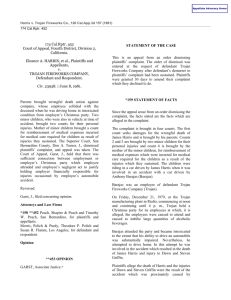

advertisement

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IMPORTANT EMPLOYMENT CASES OF THE YEAR The past year in employment law can be characterized as the year that the California Supreme Court definitively rejected the lead of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and instead relied upon its own judgments about both federal and state law. As a result, the federal courts are no longer presumptively the better place to be for employers. One of the most important developments of the past year was the affirmation by the California Supreme Court that employment discrimination claims under state law (e.g. the Fair Employment and Housing Act) may be the subject of mandatory arbitration agreements, and a specification of the requirements for such an agreement to be enforceable. In general, the arbitration procedure must provide the employee with the full remedies available under the statute; it must not cost the employee more than s/he would be required to spend in a court case; it must provide for adequate discovery; and, to allow judicial review, it must require the same findings from the arbitrator as would be required from a judge acting as finder of fact. Armendariz v. Foundation Health Psychcare Services, Inc., 24 Cal. 4th 83, 99 Cal.Rptr.2d 745 (Aug. 24, 2000). However, although a California Court of Appeal had previously ruled that an at-will employer may terminate employees who refuse to sign an arbitration agreement, in the same case (i.e. the identical factual setting and the same employee) a federal district court enjoined an employer from requiring employees to arbitrate their Title VII claims. EEOC v. Luce, Forward, Hamilton & Scripps, 122 F.Supp.2d 1080 (C. D. Cal. 2000). Both the United States Supreme Court and the California Supreme Court considered the effect of evidence in an employment discrimination case that an employer’s “legitimate business explanation” of a challenged decision was untrue. The United States Supreme Court held that evidence of pretext, combined with the plaintiff’s prima facie case, may be sufficient to support a finding of discrimination on a prohibited basis. It indicated, however, that the determination of whether an untruthful explanation is sufficient to defeat summary judgment (or directed verdict) depends on many factors, including the quality of the evidence of untruthfulness and the evidence of a nondiscriminatory reason for the employer’s decision. 1 Reeves v. Sanderson, 530 U.S. 133, 120 S.Ct. 2097 (2000). While citing Reeves, the California Supreme Court concentrated more on the need for quality evidence than it did on the finding that evidence of untruthfulness or pretext may be sufficient, along with the prima facie case, to defeat summary judgment. In fact, the California Supreme Court held that that an inference of intentional discrimination could not be drawn solely from evidence that an employer lied about its reasons. Guz v. Bechtel National, Inc., 24 Cal. 4th 317, 100 Cal.Rptr.2d 352 (2000). In discrimination cases, the major developments of the past year have been in the areas of disability discrimination, retaliation, and remedies. With respect to the former, the courts - - particularly the state courts - - have been active in evaluating what kinds of conditions merit protection and the extent of employers’accommodation obligation. Even without the recent amendments to the Fair Employment and Housing Act clarifying that a limitation need not be substantial or affect activities other than working to be protected, the courts have been expansive in their interpretation of protected disabilities. Further, the Ninth Circuit has held that under federal law, unlike California law, danger to the plaintiff is not a defense to a failure to hire or assign. Echazabal v. Chevron USA, Inc., 226 F. 3d 1063 (9th Cir. 2000). But the courts have been even more expansive in their interpretation of the employer’s obligation to affirmatively explore - - over and over again - - possible accommodations to a known disability. Particularly noteworthy are indications that poor performance reviews can constitute notice to the employer that a prior accommodation is not sufficient, requiring a search for other possible accommodations. See, e.g., Humphrey v. Memorial Hospitals Association, __F. 3d __, 2001 WL 118432 (9th Cir. Feb. 13, 2001); Spitzer v. The Good Guys, Inc., 80 Cal. App. 4th 1376, 96 Cal. Rptr. 2d 236 (1st Dist. 2000). Seniority systems not incorporated into a collective bargaining agreement may not be a defense to a failure to accommodate an employee by reassignment to another job. Barnett v. U.S. Air, Inc., 228 F. 3d 1105 (9th Cir. 2000). With respect to retaliation cases, the most interesting developments are the expanding definition of “adverse treatment” and especially the trend toward making employers liable for the shunning or other hostile acts of coworkers toward a complaining plaintiff, see, e.g., Fielder v. United Airlines, 218 F. 3d 973 (9th Cir. 2000); Thomas v. Department of Corrections, 77 2 Cal. App. 4th 507, 91 Cal. Rptr. 2d 770 (4th Dist. 2000), and the growing difficulty, at least in federal courts, in obtaining summary judgment on retaliation claims. See, e.g., Ray v. Henderson, 217 F. 3d 1234 (9th Cir. 2000); Fielder v. United Airlines, supra. As to remedies, the United States Supreme Court recently agreed to decide whether “front pay” is included in the $300,000 cap in 42 U.S.C. §1981(a) (which applies to Title VII, the ADA, and other discrimination statutes) for damages other than back pay. Pollard v. E.I DuPont de Nemours Co., 213 F. 3d 933 (6th Cir. 2000), cert. granted, ___U.S.___, 121 S. Ct. 756, 2001 WL 12416 (Jan. 8, 2001). The California Supreme Court decided (in a non-discrimination case) that in-house attorneys are entitled to attorneys’fees where available by statute or contract. And a California Court of Appeal decided that an employer must indemnify a supervisor for the expenses of defending himself in a sexual harassment case, where the alleged harassment consisted of sexual banter. The California courts continued to develop wrongful termination law. The California Supreme Court held that with appropriate notice, an at-will employer could change its policies and procedures, and continued employment constitutes acceptance of such a change. Asmus v. Pacific Bell, 23 Cal. 4th 1, 96 Cal.Rptr.2d 179 (2000). However, the policies that an employer does have may create implied contractual requirements. On the other hand, longevity, raises and promotions are not, without other evidence, a contractual guarantee of future employment security. Guz v. Bechtel National, Inc., supra. One Court of Appeal held that terminating an employee for his failure to sign an agreement containing a non-compete clause was a violation of public policy. D’Sa v. Playhut, Inc., 85 Cal.App. 4th 927, 102 Cal.Rptr. 2d 495 (2d Dist. 2000). As mentioned before, a federal district court believes that terminating employees who refuse to agree to arbitration of Title VII rights violates public policy. EEOC v. Luce, Forward Hamilton & Scripps, supra. Employers should watch the developments following the National Labor Relations Board’s ruling in Epilepsy Foundation of Northeast Ohio, 331 N.L.R.B. No. 92, 164 LRRM (BNA) 1233 (July 10, 2000) holding that 3 non-union employees may insist that co-workers be present at any employee interview that the employee reasonably believes may lead to the imposition of discipline. While long the rule in the union setting, many commentators believe that the NLRB has overstepped its bounds by extending the rule to non-union companies. Last but not least, the California Supreme Court has sanctioned the ability of individual plaintiffs - - even those unaffected by a practice - - to seek under unfair competition laws restitution to affected persons of monies which have been unlawfully withheld, most often in an alleged violation of wage laws. However, fluid recovery funds, disgorgement of profits and similar remedies require that a class action be certified. Cortez v. Purolator Air Filtration Products Co., 23 Cal. 4th 163, 96 Cal.Rptr. 2d 518 (2000). 4