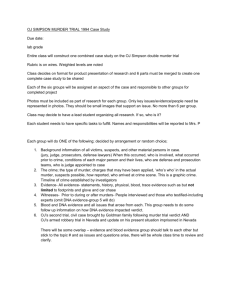

a new homicide act for england and wales?

advertisement