This article was originally published in Supply Chain

advertisement

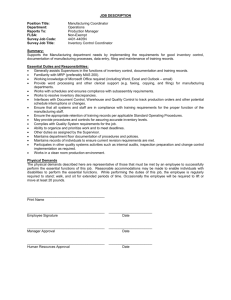

This article was originally published in Supply Chain Management Review, April 1, 2004 HOW GILLETTE CLEANED UP ITS SUPPLY CHAIN In 2002 Gillette knew it had a problem. Service levels were low, supply management was spotty, and customers were angry. The solution: reengineer the organization based on the premise that the value chain begins and ends at the retailer’s shelf. The results to date have been impressive – customer service levels up by 10 percent, inventories down by 25 percent, costs cut by 3 percent. Here’s the inside story of a remarkable comeback. By Mike Duffy, vice president of the North American Value Chain for The Gilette Co. It was not a comfortable meeting. In fact, it started out more like a confessional. Gathered at the 2002 conference of the National Association of Chain Drug Stores, our senior managers were face to face with many of our most important customers. The executives were admitting that Gillette had failed to meet its goals for effective customer service. In personal care products – deodorants and shave preparations – our performance had been especially awful. Gillette managers conceded that customer service levels in personal care lines were in the low 80-percent range despite earlier expectations that overall service would be at 98 percent by the first quarter of 2002. The big admission: While Gillette’s products were constantly in demand, the company could not reliably ship to its customers’ requirements. Our drug-store customers then heard that Gillette was applying plenty of effort to deal with their disappointments. They learned that our chairman, Jim Kilts, had named the issue as his “number-one frustration” and had insisted on urgent fixes. Gillette’s president, Ed DeGraan, was now directly responsible for rapid improvements. Other management changes put more attention on customers’ concerns. And we’d hired a top-tier consultancy to help rebuild our processes and capabilities. We also told our customers that we had already launched an integrated improvement initiative – called our “Func10 DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 tional Excellence” program – with major initiatives addressing planning, manufacturing, order management, and deployment/delivery. This program had been created with significant input from four of our largest customers in North America and Europe. The customer meeting ended with familiar commitments to making progress throughout 2002; our managers pledged to provide regular communication on our progress. “We know you’ve heard this all before,” they said. “We know it’s time for deeds, not words.” But given our past performance, it’s unlikely that many customers left the room convinced that Gillette was about to become a world-class supplier. However, that is exactly what happened over the next 18 months. Our North America operations increased customerservice fill rates by 10 percent, slashed inventory by 25 percent, and reduced cost by 3 percent. Equally important, we revitalized our value-chain organization and further strengthened our relationships with retail partners. In fact, we have won plaudits from several leading customers – including the “vendor of the year” award from Wal-Mart – and found many of our new processes being emulated by retailers. The tremendous progress made in such a short time has transformed our commercial organization. Sales calls can now focus on building the business rather than fending off concerns about custo- mer service. There have been significant shifts in the company’s mindset that will serve Gillette well from now on: a new view that the value chain starts and ends at the retailer’s shelf and an emphasis on continuous improvement. (See sidebar on page 16 “Putting Shelf Before Self.”) The overhaul did not happen by implementing sophisticated software. It came from a focus on process and people. Specifically, it meant spotlighting four key areas: (1) minimizing complexity, (2) improving demand planning, (3) improving product supply, and (4) implementing a new value-chain organization. This is how it happened. THE INVENTORY DILEMMA The Gillette Company sells more than just shaving gear. Famously known for its Mach3 and Venus razors, Gillette has a broad portfolio of products, including Right Guard mens’ toiletries, Braun Appliances, the Syncro shaver, ThermoScan, Duracell batteries, and Oral B dental care products. Our brands are among the strongest in the world – and they’re getting stronger. In Business Week’s 2003 survey of global brands, Gillette moved up to 16th place in the global rankings and Duracell pegged 71. Gillette’s 2003 sales revenues were about $9.25 billion, with 42 percent coming from blades and razors, 22 percent from Duracell, 13 percent Braun, 14 percent Oral Care, and 9 percent Personal Care. Our profit from operations was about $2 billion, with more than twothirds of that from blades and razors, 16 percent from Duracell, and 10 percent from Oral Care. The products are distributed by giant retailers such as Wal-Mart, Walgreens, CVS, Costco, and Target. We also sell to household-name chains such as Best Buy, Staples, Toys”R”Us, Lowe’s, Home Depot, and Bed, Bath and Beyond. But our brand power and the popularity of our products masked a hard reality. We just could not get product to the channel efficiently. In the first quarter of 2002, customer service was at 90 percent, as defined by first-time fill rate. Putting it in more emotional terms, customers were screaming because, on average, 10 percent of their orders were not arriving. Inside Gillette, there were constant battles. The sales guys felt like the product wasn’t there. They were frustrated because they had a hard time selling in new products (and new products are our lance sheet – less working capital in the form of inventory – and wanted us to generate more free cash flow. lifeline) because all that the buyers wanted to do was talk about the current product orders we could not fill. The supply chain guys felt like the inventory was there but they couldn’t explain why the product was not getting shipped. When we dug into it, both sides were right. Often – in at least one out of three cases – we did have product available, but we weren’t shipping it. Customers were ordering discontinued product instead of newer versions; pricing errors were preventing orders from going through. Those were just some of the pain points we were experiencing. The inclination was always to add inventory to protect service. But it was clear that the old axiom “throw inventory at a service problem” did not hold true at Gillette. It was frustrating that our inventory levels – days of inventory on hand – were among the highest in our industry. We benchmarked against competitors such as Procter & Gamble, Colgate, and Unilever. We looked at metrics such as finished goods and work in process (WIP) inventory and found our competitors turning their inventory much faster than we did – typically at least 50 percent faster. Those truths were quite evident to Wall Street. As a longtime public company, we are covered by many financial analysts, and they understood our problems very well. They could see clearly that our working capital as a percentage of sales was around 20 percent – not exactly the best way to utilize free cash. Investors were expecting us to have a stronger ba- opportunity. Over the course of about a month, we surveyed both internal and external customers on quantitative metrics such as customer service, inventory, and cost. (Exhibit 1 gives the benchmarking framework.) Internally, we polled key staff in sales, marketing, and manufacturing. The feedback was both detailed and blunt. Here are three samples of how Gillette’s own managers graded its supply chain performance: 11 DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 GAUGING THE PROBLEM Spurred on by continuing customer complaints, our Functional Excellence program set out to reverse the company’s paradoxical “poor service, high inventory” situation. The program was spearheaded by a special project team whose objective and charter had been agreed to by the senior vice president of global supply chain management, Mike Cowhig, and by Joe Dooley, our president of North America Commercial Operations. As Gillette’s director of global supply chain at that time, I led the project with assistance from McKinsey consultants. Ed DeGraan, Gillette’s president, was the chief project sponsor. Step one was to benchmark against our competitors to identify areas of early First ship fill rates (FSFR): “None of the business units is consistently achieving better than 95-percent FSFR. Key customers frequently receive less than 95-percent FSFR from at least one business unit. This issue is the driver to many other issues. In a recent customer service benchmark study based on 2000 data, Gillette’s fill rates were 35th out of 36 respondents.” Grade: Poor. Order fulfillment leadtime: “Gillette’s order cycle time is unacceptable. Benchmark comparison has Gillette...tied for fourth worst versus 36 consumer-packaged-goods companies.” Grade: Poor to average. Expediting rush orders: “Gillette is quite willing to expedite orders given our fill rates, and often does expedite orders. Cost is often a secondary consideration.” Grade: Average. Few comments ranked our performance higher than “average“ in 14 categories. Overall, the results showed that while we had generally done a good job optimizing within the four walls of our traditional supply chain functions – demand planning, supply planning, order management, and warehousing – our “end-toend“ process, from factory palletizer to the customer‘s shelves, was poor. If that first step was humbling, the next step was dismaying. It was time to communicate the outline of the program to our best customers. In the second and third quarters of 2002, our leading sales teams and I visited our top 10 accounts to do in-depth reviews of our current performance, their expectations, and our plan. Needless to say, they had little time for our plan (“we’ve heard it all before”), and they spent most of the meetings talking about the ongoing problems. To understand the contributors to poor performance, we scrutinized all KONFERENCE Vær opmærksom på at du ikke blot har mulighed for at læse om Gilettes erfaringer med at forbedre sin forsyningskæde i nærværende artikel, men også for at høre de mere specifikke detaljer herom på årets planlægningskonference, der finder sted den 25. november i København. Konferencen vil blive indledt med en forfriskende præsentation fra Heasun Choung, Operational Forecast Manager og Helle S. Breinholt, Demand & Inventory Planning Manager fra Gillette, som vil tage os igennem den forandringsproces, virksomheden har gennemgået de sidste fire år. Fra at være en organisation med en standard forsyningskæde har Gillette i dag udviklet sig til en decideret værdikæde-organisation, hvor fokus ligger på kunden, og den overordnede strategi og mission er integreret med den kommercielle del af forretningen. Gillette vil endvidere give et nordisk perspektiv på, hvordan efterspørgslen i markedet i dag integreres og matches med udbudet af varer, hvilket har givet store omkostningsbesparelser i hele organisationen. Desuden kan du høre indlæg fra DLG, Lauritz Knudsen, ECCO og Novozymes. Læs hele programmet på www.dilf.dk, hvor du også kan tilmelde dig. functions involved in the planning and execution cycle to better define their interdependencies and linkages. The goal was simple: improve customer service while reducing inventory and cost. End-to-end process mapping quickly revealed big disconnects among key processes. Multiple shipments were routinely required to complete an order. Up to 20 percent of all cases ordered shipped from an alternate distribution center (DC), making late deliveries much more likely. There was little or no close monitoring of delivery performance to the buyers’ requested delivery dates. Supply risks were frequently not identified, and when they were, the risks were not fully appreciated. As we dug into the data, several process flaws became clear: 1. Timing was not synchronized. We had planning cycles that were not aligned with one another. For example, the demand plan for the following month was often finalized one week prior to the month’s starting, even though leadtimes for deploying product to the distribution centers were, on average, two weeks. This misalignment often led to customer-service problems, especially for our U.S. West Coast customers. We had no process for communicating changes to the demand plan during any month, even though actual customer orders, promotional plan changes, and other factors may have warranted it. The factories were given a schedule at the beginning of the month; they simply produced to it. 2. Definitions did not match. Functional areas often did not understand and measure against their internal customer’s requirements. They defined and tracked measures on how they performed compared to their span of control, not in relation to how the entire process performed. For example, product was often arriving late at the DCs for final shipment to our customers. Analyzing the data and researching the root cause, we found that distribution defined a shipment as “on-time” if its actual transit time was within the standard time provided by our carriers. On the other hand, planning was expecting the product to arrive by a particular date. This date was driven by a standard cycle time, not solely by transit time. This disconnect led to product arriving late (as defined by planning), driving inventory levels higher and, tations and best-in-class characteristics, and determined our desired level of performance. A crucial part of the process was to map the entire fulfillment process, from earliest forecast through order placement to delivery to the customers’ actual shelves. We effectively “stapled ourselves to an order,” sketching out the necessary key performance indicators (KPIs) that we could later refine and use to monitor and control the processes. Inevitably, the finger pointing continued. Everyone wanted to climb back in their holes and blame each other. It was suppressed, of course, whenever it was necessary to present to the project’s steering committee, chaired by Ed DeGraan. To combat the finger-pointing, it was important to have members of both the demand side and supply side on the project team. But the best way to break it down, we found, was to focus on the data itself. The shift in focus soon began to work. in some cases, hurting customer service. 3. Accountability was limited. The best example here is around the ownership of customer-service metrics. Everyone complained about our poor service levels, yet nobody owned the metric. Different functions were responsible for “their piece” and measured their individual performance. However, no one owned the “end-to-end,” leading to finger pointing and turfprotecting. There was little disagreement that out-ofsync data led to pricing errors, ordering errors, and much more. And there was no argument that in cases where data were inadequate or nonexistent, better data had to be developed. With the fundamental data gathered, we ran a gap analysis to prioritize the program’s initiatives. The analysis helped us identify 11 key levers as core elements to our turnaround program. These levers were easy to bundle into our four initiatives of minimizing complexity, improving demand planning, improving product supply, and implementing a new organization. (Exhibit 2 lists the key levers under each of these areas.) With the early diagnostics complete, we synthesized the results to assess current performance, identified customer expec- Service/reliability Activity Expectation 1. Poor 3. Avarage 5. World Class Gillette Score Benchmark Companies Measurement 5 Gillette sporadically provides/monitors joint scorecard Gilette regulary provides/monitors joint scorecard on exception basis, collaborates to identify/implement improvement opportunities Gillette regulary provides/monitors joint scorecard, proactively recommends opportunities to improve service/ reduce cost 1 Procter & Gamble Lever Elida L’Oreal First Ship Fill Rate 5 Gillette’s average fill rate < 95% Gillette has an average fill rate between 95% and 98% Gillette has an average fill rate greater than 98% 1 Colgate Palmolive Lever L’Oreal 5 Gillette’s average time elapsed from order placement to product delivery is longer than our requirements Gillette’s average time elapsed from order placement to product delivery meets our requirements Gillette’s average time elapsed from order placement to product delivery exceeds our requirements 1 Kellogg’s Definition: Number of Units Shipped Against Number of Units Ordered on First Delivery Against That Order Order Fulfilment Leadtime Definition: Lead-time From Receipt Of Order to Delivery Of Order Exhibit 1. Sample of Benchmark Framework 12 DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 Minimize Complexity Our detailed analysis revealed that poor processes were prevalent up and down Gillette’s supply chain. “Band-Aids” and quick fixes had become institutionalized. Further, SKUs had been allowed to proliferate wildly. For instance, there were too many customer-specific SKUs (always a challenge) and a wide array of SKUs specific to the Canadian marketplace. Looking at the situation dispassionately, we could see that poor process discipline combined with an inordinate amount of complexity was a disaster waiting to happen. The solution was obvious. We launched a comprehensive program to eliminate thousands of SKUs and manage them properly. We built a new reporting tool that each month could pull data from our SAP enterprise resource planning software and automatically flag SKUs that failed to clear the performance hurdles that we set. Under-performing SKUs were reviewed by the business team, and at least 30 percent have been eliminated. There had been quite a few “dead” SKUs in the system. We have harmonized most of the Canadian SKUs with their U.S. equivalents. In many cases, it was as simple as making sure that Canadian and U.S. products used the same packaging graphics. The initiative brought immediate benefits. It has improved the focus of the demand planners, who have fewer SKUs to forecast; made production processes more flexible because there are fewer changeovers; and given us faster inventory turns. Our finished goods inventory turns have improved by 25 percent in the last three years, from around 4.8 turns to just under six. The simplification extended to the order-to-delivery process. Many processes Improving ValueChain Performance Increase Service Reduce Inventory Lower Cost mand planners. Previously they had reported to the general managers in the sales function; but now they reported to a dedicated director of demand planning, a new position. The result is that we get a less filtered view of the demand signals. The next area concerned SKU forecasting of open-stock items – the regularturn items that are constantly replenished on the shelves. We had Manugistics software in place, but we weren’t leveraging its full capabilities to model the transaction history and to incorporate business intelligence. We brought in our IT experts – they’d been part of the project planning from the get-go – to help us refine the tool. At the same time, we trained our planners on statistical modeling and tool usage so we could take full advantage of the software’s capabilities. On another front, we hadn’t been using account-level forecasts to derive our demand plan. With top-down planning, Improve Demand Planning there was no need. Information from our customers was readily available, but it was unusable because there was no process to incorporate it. For example, some key accounts could generate order forecasts, but we could not determine if that information was better than our own internally generated number, and we missed the opportunity to discuss with the customer why the numbers were different. Now we’re partnering with some of our key accounts on collaborative order forecasts, not only for open stock and promotional forecasts but also for any activity that might affect consumer demand. Our next focus area was promotions. Historically, we had concentrated on the dollar accuracy of forecasts rather than the unit accuracy. As a result, we had plenty of shipment inaccuracies; the dollar figure may have been right but the actual shipments failed to meet customer requirements. We now work closely with sales to ensure that dollar forecasts are translated into unit forecasts and that all parties own and are held accountable for that final expectation. Decomposing the overall demand plan down to finer buckets such as open stock and promotions has enabled focused improvement efforts (see Exhibit 3). While variability in the supply chain is never good, its impact is dampened if it can be predicted. Segmenting the forecast has allowed us to accommodate spikes in demand that we know will occur due to factors such as seasonality and promotions. Concurrently, we had to overhaul our demand-planning processes. Gillette did have such processes, but they were not effective. We had a top-down approach to planning – an approach that was focused on a financial number rather than a unit planning number and reflected a goal for what we wanted to sell, not a clear-eyed view of how many units we really could sell. In essence, it’s an approach that encourages employees to think about what management “wants me to ship” instead of focusing on what customers really might buy. So our first area of focus was on unhooking the financial commitment from the demand plan. That enabled us to generate an unbiased prediction of true customer demand or “what is most likely to happen.” We also transplanted the de- Minimize Complexity Order/Shipment Volatility SKU Rationalization Promotional Complexity Reduction Improve DemandPlanning Processes Open Stock and Promotion Planning Long-Term and ShortTerm Planning processes Improve SupplyPlanning Processes Manufacturing Flexibility Order-To-Delivery Leadtime Inventory Planning Establish Optimal Support Systems Exhibit 2. The Diagnostic Identified 11 Key Levers 13 had become unnecessarily complex because Band-Aid solutions had been applied to many customer service issues, leading to inevitable service breakdowns. One example: Gillette regularly shipped to customers from any one of our four distribution centers. We may have been deploying inventory to a DC based on a forecast, but we were really shipping from whichever DC had inventory. In 2002, fully 11 percent of our shipments originated from an “alternate DC.” That caused inventory levels to balloon unexpectedly in some locations and shrink in others, making forecasts inaccurate and causing huge inventory imbalances throughout the distribution network. Today, the alternate DC number is down to 1 percent. This decrease not only helps us plan more accurately but also gives our customers more predictable cycle times for their deliveries. DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 Organization Performance Management IT Systems Improve Product Supply We concentrated initially on manufacturing flexibility. To illustrate, we had some SKUs that our factories would produce once every eight weeks. Given the product categories we compete in, we needed more flexibility to better respond to the marketplace. Now we’ve increased the run frequency of most SKUs, better matching supply-side capabilities with the needs of the business. Similarly, we’ve improved the inventory-planning process. Historically, our inventory planners would use their experience to set levels of SKU safety stock. They would set safety-stock levels at the product-family level, so nuances at the SKU level – forecast accuracy, demand volatility, and manufacturing-run frequency, for instance – weren’t taken into account. The planners were typically giving everybody 35 days’ inventory instead of really understanding the SKU requirements. Additionally, inventory levels were only reviewed semi-annually. Now we’re continually looking at ways to improve every component of our inventory by examining the key improvement drivers, as depicted in Exhibit 4. With deeper analysis, we were able to match customer needs with the need to minimize stocks of finished goods. Improved supply planning allows us to set safety-stock levels more appropriately. In addition, focused training and education has helped our planners become more scientific in how they establish safetystock levels. Inventory is used “intelligently” to buffer the variability of demand against the variability of supply. Where we have predictable demand and predictable supply, we can trim back inventory levels. In some cases, we are finetuning just-in-time deliveries and vendormanaged-inventory shipment schedules. If both demand and supply are unpredictable, we compensate by increasing inventory. Additionally, we have done much to clean up system data. Previously, orders would get hung up in SAP because product or documentation definitions were not synchronized. It was quite common for customers to order discontinued product and for the system to kick out error messages or messages requesting new orders. We’ve really worked hard to collaborate with our customers on uniform data. Gillette and our customers. (See Exhibit 5.) The old supply chain group had been responsible for inventory planning, freight, and warehousing. The sales organization was responsible for demand planning, promotions management, and customer service – with each of those functions reporting to a different vice president. The new value-chain alignment brought together contributors from both sides under one management team. Single-point accountability for customer service, inventory, and cost to serve presented a huge opportunity. It meant colocating staff, focusing everyone on stocking customers’ shelves efficiently, and regularly reviewing our performance. I implemented a weekly service review meeting with representatives from each group looking at the previous week’s successes and failures. (The first meeting la- Restructure the Supply Chain Organization sted three hours; people were not prepared, and there was still plenty of blame being passed around. Now the meetings are down to half an hour maximum, and there’s no finger-pointing any more.) By moving to an integrated organization, it was our belief that we would: The initiatives described so far would not have been fully effective had we done nothing to align key roles with the new processes. Essentially, we had to migrate from a segmented supply chain structure to an integrated value-chain organization. The redesigned organization allows us to own all the levers required for improving performance. We can make investments and process changes that can deliver substantial benefits to both 1. Get a more complete understanding of the end-to-end process. As referenced earlier, we had functional experts not value-chain experts. While everyone was working hard against his or ���������� ��� ����������������� ������������������������ �������� ��� ��� ��� �� � � � � � � � � � �������� ��� ��� ��� ������� ��� ���������� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� �� � � � � � � � � � �� � � ��� �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � ������������ ��� ��� ��� ����� ��� ��� �� ��� ��� ��� �� Exhibit 3. Example of Segmenting Demand 14 DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 � � � � � � � � � � � Component of Inventory 100 Key Drivers to Inventory Improvement Prebuild New Product Launches Raw Material/WIP Vendor flexibility/Consignment Excess Not Perfect Plan/Execution Slow/Non-moving Phase In/Phase Out, Batch Sizes Safety Stock Forecast Accuracy, Replenishment Leadtime Cycle Stock Manufacturing Flexibility In-Transit Sourcing Locations/DC Network Exhibit 4. Spotting Inventory Opportunities her objectives, they were not always working towards the same goal. A single organization allows objectives to be aligned, and it ensures that the process flow from one group to another is better defined and synchronized. 2. Have better and faster communications across all functions of the value They had a presence on the program’s steering committee, and they provided vital guidance and counsel for both managers and employees. For example, when we restructured the reporting lines for our demand planners, HR actively worked with us to change the planners’ objectives. Since the planners would no longer be working for chain. Like many companies, we struggled with the speed at which we turned data into knowledge. With a single organization focused on the customer, we are able to move information across the value chain faster, accelerating the decision-making process and improving the odds of continued success with our customer. 3. Gain a more coordinated understanding of the processes within our customer supply chain. Historically, we had not done a good job of understanding customers’ supply chains. Mistakenly, we believed our job was done once we shipped the product. Our new value-chain orientation means we now partner with our customers to understand how our product moves through their system. That way, we can readily spot and eliminate redundancies and inefficiencies in the entire system – from source to shelf. 4. Provide one voice to the customer for all value-chain issues. We had many vice presidents responsible for various aspects of the value chain, but no one accountable end to end. Resolving service problems became exercises in frustration for internal and external customers alike. With a single point of accountability, customers now have “one-stop shopping” for issue resolution. the sales organization and therefore would not be eligible for sales bonuses, HR helped us redesign their compensation packages to ensure that they came out even. Now the planners are compensated based on their contributions to customer service, inventory levels, and cost containment. It helps shift the focus from “this year’s bonus” to a longer-term view centered on the customer and on continuous improvement. Throughout, we had the invaluable input of Gillette’s human-resources group. 15 DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 GAUGING THE IMPACT How have we done? Gillette is effectively a different company; all the metrics underlying the success of our organization have improved. Forecast accuracy, measured at the monthly item level in the DCs, climbed from 46 percent in January 2003 to 71 percent in November of last year. Fill rates increased from around 90 percent in 2003’s first quarter to 98 per- �������� ������� cent at the end of the year. Inventory levels are down substantially in the last year; in addition to expanding our customer service vocabulary, we now include ontime delivery and order-to-delivery cycle times as part of our daily KPI review process. There’s been good recognition of the gains to date – both internally and externally. Gillette’s chairman, Jim Kilts, has made note of the improved customer-service activity, and last summer, the head of our personal-care products operation gave the value-chain organization an award for the improvements his unit had seen. Outside, the free cash flow now being generated has met with investors’ approval (working capital that recently ran around 20 percent of sales is now in the single digits), and Wall Street analysts have noted the improvements in days sales outstanding and inventory on hand. At least one investment bank has since upped its rating of Gillette’s stock. The bigger win has been the revitalization of the organization. Everyone not only is focused on delivering value to the customer but also has become re-engaged with each other. When issues arise, we resolve them with the root-cause analysis and fact-based decisions. By focusing on the data, we’ve taken emotion out of decision making, allowing process fixes to be implemented much more quickly. But it’s the direct customer feedback that has been most gratifying for our team. Yes, we did clinch the “Vendor of the Year” award from Wal-Mart last year—a major boost given Wal-Mart’s well-deserved reputation for toughness. In many cases, though, we derived more satisfaction from smaller signals that we were on the right track. One brand-name retailer was delighted that we asked for their candid feedback on our supply ����������������������� - Case Fill Rate - On-Time Delivery - Perfect Order/Invoice ����� ����� ��������� - Investment $ - Coverage - SKUs Exhibit 5. All Key Levers Under One Management Point ��������������� - Warehousing - Transportation - Systems/Data - Continuous Process Improvement chain performance; no other vendors had ever asked them for that. Another asked for much more detail on the process so they could assemble it into a training manual for use by their other suppliers. Still another was amazed at the levels of detail that we explored. When we stapled ourselves to an order from that customer, we had used a total of 71 Post-It notes to show them what the transaction looked like. That level of detail was part of what made Functional Excellence so successful. KEY COMPONENTS OF SUCCESS Gillette’s lackluster supply chain performance was by no means unusual, and our remedies were not particularly innovative. In fact, our transformation story could be that of any company facing similar pressures and armed with similar resources. We did not overhaul our software platforms or spend lavishly to push Process first, organization second. Many companies rush into an organizational change without fully understanding the underlying processes that need fixing. At Gillette, we focused on detailing the processes involved in the entire planning and execution cycle, identifying the gaps, and systematically closing them. Once the processes were defined, we implemented the organizational structure required to sustain the improvements. The devil’s in the detail – get into them. Here’s an example: We previously reported customer-service metrics two weeks after the month’s close. This gave us little opportunity to research the causes of failure. We had volumes of reports listing last month’s KPIs, but little detail on the causes of failure; in essence, we were data-rich but information-poor. Now we report customer service metrics, gauged by distribution center and by business unit, every day. through the necessary changes. Instead, we took advantage of a healthy climate for change, carried out exhaustive analyses, gave project leaders authority as well as accountability, and focused foremost on what would improve value to the customer while minimizing our cost of working capital. We believe the following elements were crucial: Senior management support and buy-in. It seems obvious, but without the support of senior management, organizational change is rarely possible and never sustainable. At Gillette, senior management gave us the time and, more importantly, the resources required to make the changes. Additionally, we have a cross-functional team that meets daily to research the previous day’s service failures. The team does not assign blame or point fingers but identifies both the issues leading to the service gap and the necessary processes required to eliminate them. Align the organization around objectives. The best way to get an organization focused on a common goal is to share objectives. Co-location of people certainly helps enable communication. But if you really want to accelerate the “ability to get things done,” have them share objectives. Was our Functional Excellence transformation easy? Of course not. Nor is it Category Management Item/Data Set-Up and Maintenance Demand Planning On-Shelf Availability Supply Planning In-Store Logistics Freight and Warehousing Exhibit 6. The Value Chain Cycle 16 DILForientering / oktober 2004 / årgang 41 Order/Revenue Management by any means complete. With a new continuous-improvement approach and the KPIs to back it up, we have a long list of detailed projects. Already we’re working toward using first-time on-time delivery as a core performance metric. I firmly believe that what Gillette has done, others can and should do. It’s no overnight fix – you’ll have to dig in for a couple of years at least and prepare for plenty of setbacks. But the rewards are immeasurable. / PUTTING SHELF BEFORE SELF “Out of stock” status is a huge industry problem. If we don’t partner with our customers to help solve it, we’re leaving money on the table. That’s why one of the goals of Gillette’s new value-chain organization was to change the way our employees thought about our supply chain activities. Historically, the supply chain is depicted as a linear process flowing from left to right – from source to retail shelf. Our view is that the value chain starts and ends at the shelf. It is a circular process as shown in Exhibit 6, not a sequential flow. The rationale is simple – if our products are not on the shelf when the consumer wants them, all the work leading to that point is wasted. To instill that fresh mindset, we asked everyone in the value-chain organization to imagine tracking our products from a manufacturing plant to a customer’s shelves, thinking about every step along the way and thinking of potential improvements. That mindset requires a collaborative approach with our retailers to optimize the management of the supply chain. Partnering with our customers to understand how our product moves through their supply chains, from distribution center to shelf, has been critical learning process and has enabled us to rethink many of our traditional approaches. Now our staff understands and tracks out-of-stock rates for key customers. They put themselves in specific customers’ shoes. In one recent example, we redesigned the markings on a carton to give it more prominence and a clearer identity in the stockrooms of the customer’s stores.