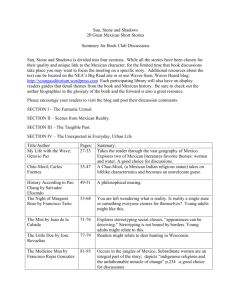

Samora Carmen EDISS May 13 2011

advertisement