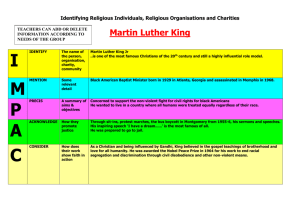

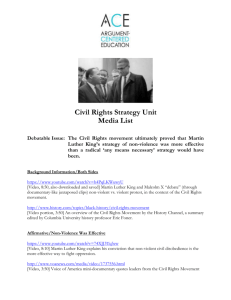

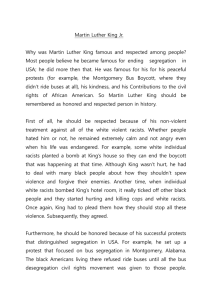

Non-violence in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States of

advertisement